Teatime is one of those quintessential English phrases, conjuring up images of steaming silver teapots served to aristocratic aristocrats, along with slices of bread and filling sandwiches.

Started with a hungry noble

The story is said to have originated with a nobleman. One afternoon in 1840, Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford, complained of “a feeling of depression.” She was hungry—and it was still four hours until dinner. Not wanting to wait, the hungry noblewoman asked her maid to serve her a light snack along with her usual pot of tea.

There are no precise records of what this meal consisted of, but it probably included some bread, butter, jam, and biscuits.

Tea, as a beverage, was also an overnight success in England. When Catherine of Braganza arrived in England from Portugal in 1662 as her new queen, she brought with her the habit of drinking tea daily.

Until then, the drink had only been used as a medicine in England, but with Catherine's approval, it quickly became a fashionable drink for the upper class.

Two centuries later, Anna Russell elevated afternoon tea. Whatever the original snacks were, they soon expanded to include a wide variety of sweet and savory dishes.

Sandwiches – delicately cut into small, soft slices – are filled with tomatoes, asparagus, prawns, caviar or even oysters. Pastries include raisin cakes, Swiss rolls, Battenberg cakes and macarons with nuts.

One of the most popular sandwich fillings is cucumber – often peeled, sliced, and served with cream cheese. While cucumbers may not be the most appealing sandwich filling, they are a status symbol. If you can grow cucumbers, it means you can own an expensive greenhouse.

Afternoon tea also received the approval of Queen Victoria. Her favorite strawberry shortcake was later renamed in her honor. The "Victoria sponge" remains another afternoon tea favorite.

Victoria sponge cake, made light and fluffy by the addition of baking powder, appeared in 1843, thanks to chemist and food manufacturer Alfred Bird.

"West Country" cream tea is said to have originated at Tavistock Abbey in Devon; workers restoring the damaged abbey after a Viking attack in 997 AD were rewarded by Ordulf, Earl of Devon, with a portion of clotted cream bread (a rich, thick cream), and strawberry jam.

Over time, bread gave way to scones: soft, bite-sized cakes made from sourdough, butter, salt and sugar, baked until fluffy, then cut in half and topped with the aforementioned jam and cream.

Afternoon tea fills the streets

Afternoon tea is more than just a place to recharge. It's a place to share the latest gossip and cement your social standing. So rules and rituals have come thick and fast.

Soon, afternoon tea spread from aristocratic drawing rooms to the fashionable streets of London. The Langham Hotel claims to be the first to serve afternoon tea to the public in its lavish Palm Court in 1865.

“In the early days, afternoon tea was a simple affair – often just a few small sandwiches and a sweet or two, designed for ladies to have between lunch and dinner,” shares Andrew Gravett, head pastry chef at the Langham.

Not only were nobles and noblewomen munching on muffins and sipping lapsang souchong, inside the mansions, servants gathered for a less lavish feast, called "high tea," sometimes accompanied by other common dishes.

Although tea was originally an extremely expensive luxury for the British, the 1784 Act of Conversion reduced the import duty on tea leaves from 119% to 12.5%, making the drink more accessible, though still quite expensive. As Swedish writer Erik Geijer stated in 1809, "Next to water, tea is the defining element of the English. All classes consume it."

The increasing affordability of tea coincided with the Industrial Revolution, creating massive new jobs in factories and construction, especially in Victorian times.

"Some factory owners thought that an afternoon snack could boost productivity; the stimulants in tea, combined with sugary snacks, could energize their workers to work all day," writes Gillian Perry in "Please Pass the Scones."

While the upper classes viewed tea as a show-off, working people actually enjoyed it as a nutritious beverage during what was known as the "tea break."

Consumed in the late afternoon, or "rush hour," afternoon tea became a well-deserved respite for Victorian workers after a hard day's work.

But while afternoon tea is a formal interlude before dinner is served later in the day, high tea, which includes more than just bread, is the actual meal. This explains why many Brits (especially those in the North) still call their evening meal “tea” – whether it’s roast meat, curry, or “chip tea”.

Afternoon tea waned during the war years when the country was short on food, but has since rebounded. Although the class boundaries around afternoon tea have blurred, it remains a refined pleasure.

“Afternoon tea is the perfect way to mark special occasions in life: birthdays, anniversaries, proposals,” says Gravett, the Langham’s pastry chef. “It strikes the perfect balance: a delicious culinary experience in an often lavish setting, with enough stage and ceremony to make every guest feel like royalty, even if only for a few hours.”

“With the rise of social media, the visual aspect of afternoon tea has become more important than ever,” says Gravett. There are now Sherlock Holmes-themed afternoon teas and Shakespearean afternoon teas; Indian afternoon teas and sushi afternoon teas. There are afternoon teas on double-decker buses, steam trains and British Airways planes.

Source: https://www.vietnamplus.vn/afternoon-return-of-the-anh-qua-khu-hoang-kim-va-tuong-lai-ruc-ro-post1081811.vnp

![[Photo] Urgently help people soon have a place to live and stabilize their lives](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F09%2F1765248230297_c-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

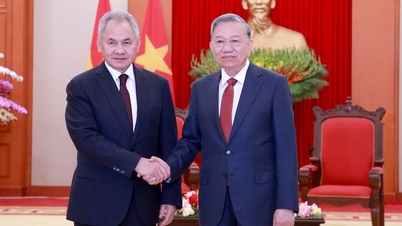

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam works with the Standing Committees of the 14th Party Congress Subcommittees](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/09/1765265023554_image.jpeg)

Comment (0)