1. Even though many years have passed since she received the Certificate of Recognition from the Fatherland, my grandmother still maintains the habit of going out to the street every afternoon, her eyes gazing into the distance down the road as if waiting for a familiar figure.

The certificate of recognition for her service to the nation was placed respectfully on the altar, covered with a red cloth, but in her heart, it wasn't the end, as she didn't know where my uncle had died, or where he was buried. Therefore, on lonely nights, she silently prayed for a miracle, hoping that perhaps he was somewhere out there, and would one day return. That belief, though as fragile as a wisp of smoke, had the enduring strength to sustain her through the long years of her life. Time passed, one year, two years, then decades, and my grandmother stopped hoping to welcome her son back alive and well, instead yearning to touch the soil where he lay.

My childhood was spent in peaceful days in my grandmother's small house. I still remember those late afternoons when my grandmother and I would sit in the corner by the banyan tree at the edge of the village, enjoying the breeze. My grandmother would always look towards the small road winding through the fields, occasionally wiping away tears. I also haven't forgotten the afternoons we spent cooking rice together, or the late nights when she would tell me about my father's mischievous antics as a child, her voice tinged with affectionate reproach. And the stories she told, though never quite finished, were memories of my uncle, a man I never met but who instilled in me a profound sense of pride and gratitude.

2. Through the stories my grandmother and father told me, I gradually pictured my uncle – a young man in his late teens or early twenties, fair-skinned, one of the most handsome in the village, with a warm smile and a studious nature. Growing up amidst the war years, my uncle volunteered to enlist in the army and fight in the South, taking with him his youth and a promise to the girl from the neighboring village.

On the day my uncle left, my grandmother picked a few ripe pomelos from the backyard and placed them on the altar to tell my grandfather, "Our boy has grown up and knows how to dedicate himself to the Fatherland. I will overcome all difficulties so that he can confidently embark on his noble mission." Before parting, she held his hand tightly, urging him to fight bravely, worthy of the family and homeland's traditions, and to always return to his mother. Obeying his mother, my uncle set off, carrying with him the belief in victory so that he could soon return to the embrace of his family. The girl from the neighboring village only had time to quickly hand my uncle a blue scarf before running to the pomelo tree and sobbing uncontrollably. My grandmother comforted her, saying, "Trust in your son, and our family will have great joy."

But then, the fateful day arrived. The news of his death from the battlefield in the South left the whole family speechless. My grandmother didn't cry; she just quietly went to the garden, picked a few pomelos, placed them on the altar where my husband's portrait was, and softly said, "My dear husband... my son has left me to be with you. Please take care of him and guide him for me..."

Every spring, when the grapefruit orchard behind the house fills with its fragrant scent, she goes out into the garden, silently like a shadow. Many days, she sits there for hours, occasionally murmuring to the clusters of blossoms as if confiding in a soulmate. For her, it's not just July 27th that brings quiet reflection and remembrance; anytime, anywhere, whatever she's doing, whether she's happy or sad, she stands before the altar, talking to my grandfather and uncle as if they had never left. Every time she sees someone on television finding the grave of a loved one after years of lost contact, her eyes light up with hope. And so, season after season, year after year, she silently waits, persistently like the underground stream nourishing the grapefruit trees in the garden, so that each year they will bloom and bear fruit.

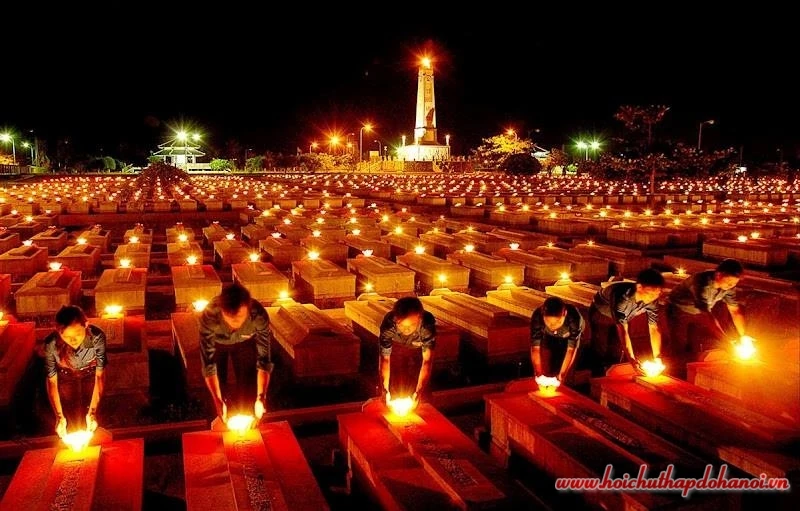

3. Whenever I have the opportunity to visit war cemeteries, I always linger for a long time before the unmarked graves, just to listen to the whispers of the earth and the wind. Occasionally, amidst the peaceful atmosphere, I encounter the image of grandmothers, mothers, and wives of fallen soldiers silently sitting beside the graves, whispering to the deceased, just as my grandmother used to talk to my grandfather and uncle back then. I also meet many veterans, those fortunate enough to return from the brutal battlefield, now with graying hair, still affectionately calling each other by names like "Brother Mia," "Sister Chanh"... They silently light incense sticks at the graves, sending with them their love, their memories, the things they never had a chance to say, and their unfulfilled dreams.

Standing before the graves of soldiers who died at the tender age of twenty, I felt more acutely than ever the loss and the never-healing wounds of mothers who lost their sons, wives who lost their husbands. I understood why my grandmother could sit for hours talking to the grapefruit tree, why she often woke up in the middle of the night... I vividly remember her face with its deep wrinkles etched like the marks of time, her neatly wrapped gray hair in a dark brown silk scarf, her sorrowful eyes, her thin hands, and the faded dress that had accompanied her through countless memorial services. I remember the stories she told about my uncle, forever twenty years old, "more beautiful than a rose, stronger than steel" (in the words of poet Nam Ha in his poem "The Country"), whom I never met.

There are sacrifices that cannot be expressed in words, pains that cannot be named. These are the sacrifices of heroic martyrs, the silent but enduring suffering of mothers, fathers, wives... on the home front. All of this has created a silent but immortal epic, writing the story of peace ... so that we can "see our homeland shining brightly in the dawn."

Japanese

Source: https://baoquangtri.vn/nguoi-o-lai-196378.htm

Comment (0)