.jpg)

Complete the circle of heaven and earth.

In Phan Huy Chú's *Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí* (Historical Records of Dynastic Constitutions), the twelfth lunar month is recorded as the time for "sweeping graves, repairing the family home, and preparing offerings." There, cleaning the house was not simply hygiene, but an act of purification.

People cleanse themselves of the old and incomplete aspects of the past year to welcome new vitality. Many family genealogies and village regulations stipulate that from the middle of the twelfth lunar month, disputes and lawsuits should be avoided; villages should prioritize reconciliation, "so that everyone can enter the new year in peace and harmony."

This way of thinking is clearly reflected in the word "year" (歲), which is always associated with the idea of completing a circle, and the twelfth lunar month is the moment when that circle closes. Therefore, rituals such as the Kitchen God worship (on the 23rd day of the twelfth lunar month) are considered important milestones, marking the official entry of the family into the period of preparing for Tet (Lunar New Year).

In texts like Lê Quý Đôn's Vân Đài Loại Ngữ, the twelfth lunar month is depicted as a busy yet orderly period: making cakes, pickling vegetables, slaughtering pigs, drying rice paper, and re-dyeing clothes. These tasks follow a familiar schedule, repeated through generations, to the point of becoming a "collective memory" of the community.

Notably, many texts mention the preparation of offerings not only for the family, but also for the village communal house. The village's year-end ceremony usually takes place at the end of the twelfth lunar month, on a large scale, with rituals, feasts, and the distribution of blessings. Therefore, Tet (Lunar New Year) is not just a private matter for each household, but a culmination of the entire community's efforts.

The filtering door

From the 17th and 18th centuries, many Western merchants, missionaries, and scholars left valuable records about life in Vietnam. In *Relation of the Kingdom of Tonkin*, Alexandre de Rhodes described that "more than a month before the New Year, the markets had become different, overflowing with goods for the holiday."

He was surprised by the Vietnamese people's meticulous preparation for Tet, marked by a high degree of patience and ritual, in contrast to the European custom at the time where preparations for the festival usually only lasted a few days. Jean Baptiste Tavernier, while traveling through the Southern region, also noted: "At the end of the year, almost all work stops, and people devote their attention to family, ancestral graves, and rituals related to the new year."

This observation suggests that the twelfth lunar month is a "time buffer zone" where economic , administrative, and social activities slow down to make way for spiritual life. An interesting detail in foreign records is the early appearance of Tet markets.

Portuguese and Dutch merchants and navigators vividly described Vietnamese markets during the end of the year and Tet (Lunar New Year), emphasizing the crowds, the bustling atmosphere, and the abundance of goods. The texts also suggest that these markets were centers of Vietnamese culture and spiritual life.

For foreigners, the twelfth lunar month market is a symbolic space where the old is sold and the new is bought, preparing for a new beginning. In many Sino-Vietnamese texts, the twelfth lunar month is also the season for "settling accounts" - summarizing land, taxes, and debts.

But alongside that are activities like releasing animals, giving alms, and doing good deeds, as a way of "paying off" moral debts before the new year. This mindset elevates Tet beyond the concept of a mere festival.

The common ground between Sino-Vietnamese texts and foreign accounts of the Vietnamese Tet holiday lies in the fact that preparations for this festival are not solely material. The twelfth lunar month is a time of deliberate slowness, of rearranging life from family to village, from individuals to their relationships with ancestors and deities.

Reading through ancient writings, one can see that Tet (Vietnamese New Year) truly arrives only when people close out the old year. And the twelfth lunar month, in Vietnamese cultural memory, is the gateway to purification and cleansing, preparing people to enter a new cycle of life.

The progenitor of Tet newspapers

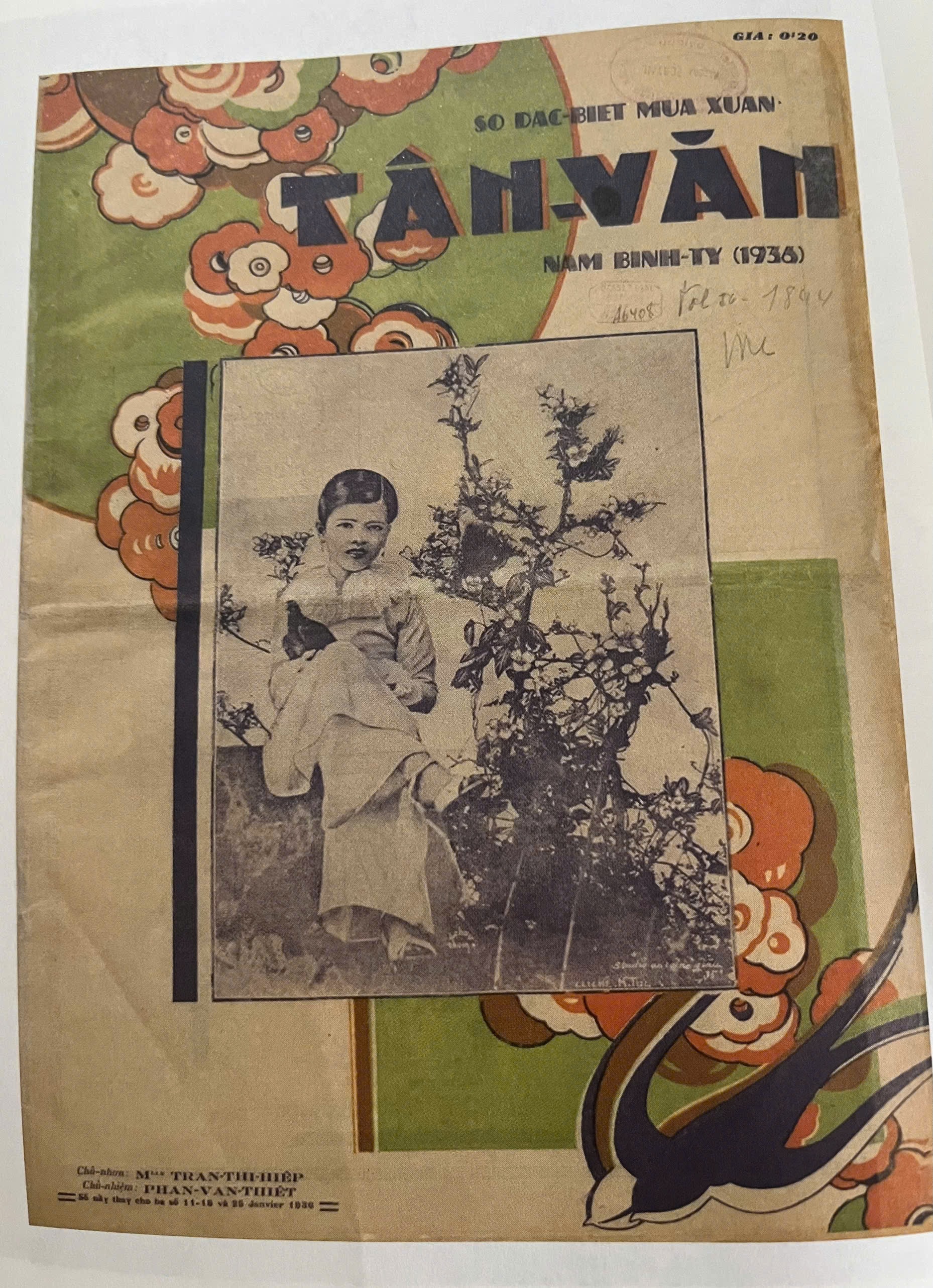

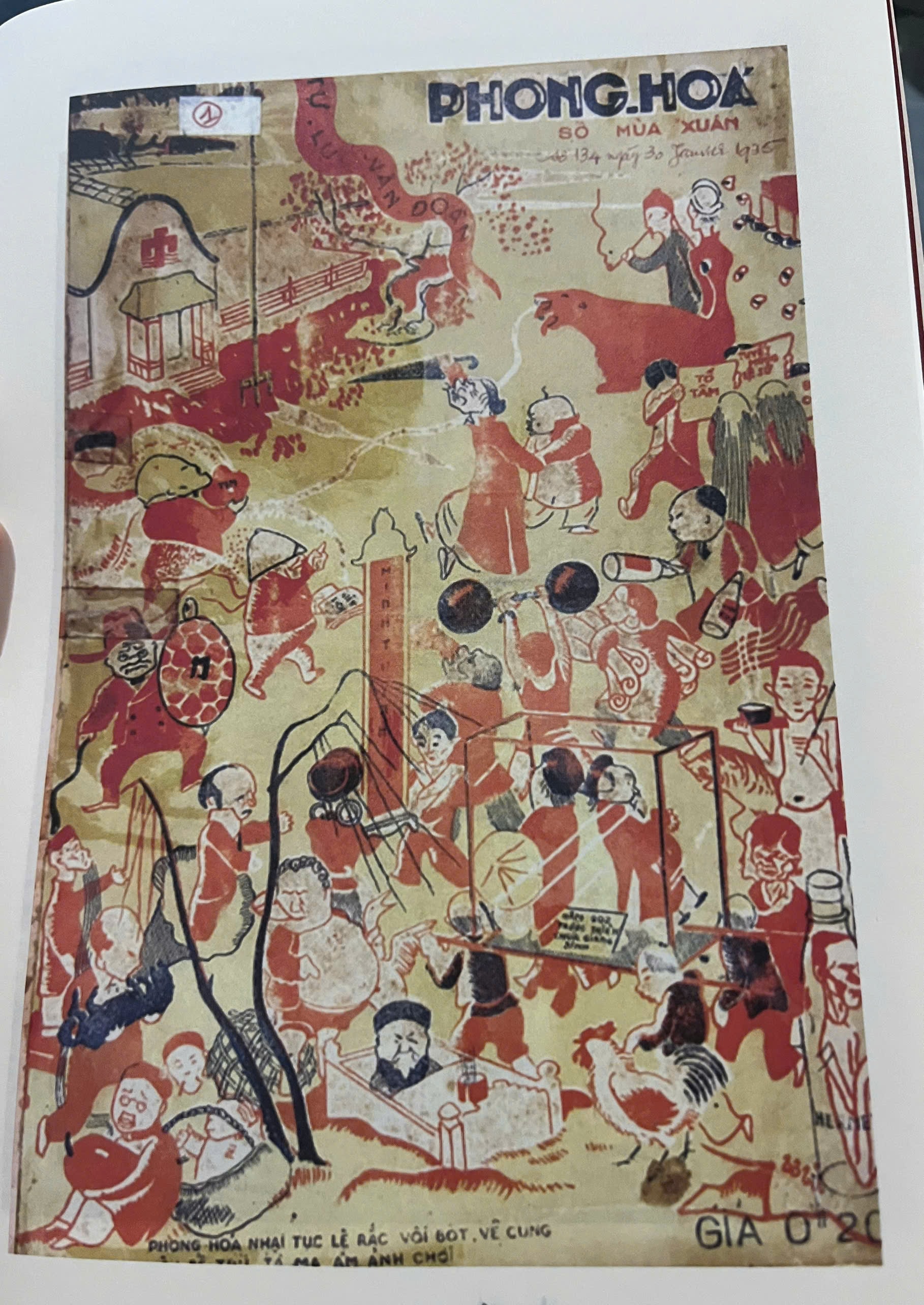

In his book "The Joy of Book Collecting," scholar Vương Hồng Sển asserts that the ancestor of Nam Phong magazine, the "1918 Tet issue," was the first Spring/Tet (Lunar New Year) newspaper in Vietnam. Nam Phong magazine (Southern Wind) was a monthly publication founded by L. Marty, a Frenchman fluent in Vietnamese, with scholar Phạm Quỳnh as its editor. Just a few months after its launch, Nam Phong released its "1918 Tet issue" with a distinctive presentation: not numbered as usual, with a light orange-yellow cover featuring an image of two old men, one bright and one faded, holding peach blossom branches, symbolizing the two high-ranking officials of the year Mậu Ngọ (holding a fresh peach blossom branch) and Đinh Tỵ (holding a branch without blossoms) exchanging seals. A key feature of the Nam Phong "1918 Tet issue" was that all articles were framed in floral frames, included numerous illustrations, and contained no advertisements. In the preface, editor Phạm Quỳnh stated the reason for creating the Tet issue: "The Tet holiday is the only joyful day of the year." "That joy is shared by everyone, a joy that permeates society, a joy that spreads throughout the nation; nowhere else in the world is there such a completely joyful celebration. Even those who are sad must be happy during Tet: the joy of Tet is easily 'contagious'..."

Society

Source: https://baodanang.vn/thang-chap-trong-thu-tich-3322847.html

![[Photo] Nhan Dan Newspaper celebrates the 96th anniversary of the founding of the Party.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F02%2F03%2F1770093917726_z7495755471262-66d965cdf06fce4e837f306802ae37b1-7408-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)