Short, clear introductions to the cultures of Southeast Asian nations are difficult to find. For years, I cobbled together collections of short articles and selections of literature for my university-level introduction to Southeast Asia and presented the historical framework in lecture. My goal was to entice students to investigate the material on their own or in a more advanced class.

On a trip to Việt Nam, an area outside my own research field in the Bahasa world of Indonesia and Malaysia, I had a chance to meet Hữu Ngọc and was given a copy of Wandering through Vietnamese Culture, a collection of his essays, which is over 1,200 pages. It served as a wonderful guide, containing answers to so many of the questions that had presented themselves. When Ohio University Press was considering publication of an excerpted version of Wandering through Vietnamese Culture, I was asked in my role as editor for the O.U. Press's Southeast Asia Series to accept the Press's invitation to make the initial selection of essays.

Hữu Ngọc originally wrote his essays as newspaper columns for international readers who, living in Việt Nam, had some acquaintance with the country. Yet all of us working on this project, including and especially Hữu Ngọc, wanted also to think of those for whom Việt Nam is completely new. Starting from an early draft Table of Contents, with Hữu Ngọc as expert and author, we worked together to crystallize his oeuvre into a first-taste introduction to Vietnamese history and culture, emphasizing the structure, factors, and individuals he feels are particularly important.

Việt Nam: Tradition and Change shimmers with Hữu Ngọc's thoughtful reflections and insight. The collection is designed for students in introductory classes and for other readers interested in Việt Nam. I hope they will also fall in love with the rich cultural heritage of the people and nation that is Việt Nam.

Hữu Ngọc's central thesis—"All tradition is change through acculturation"—twines through each of the book's ten sections and through many of these short essays. In the first section, "The Vietnamese Identity," Hữu Ngọc portrays what it means to be Vietnamese. He describes the values that shape Vietnamese character, such as the untranslatable word "nghĩa," and explores the meaning of the customs that embody Vietnamese ideals: ancestor veneration, worship of mother goddesses, the naming of a child, the arrangement of a traditional Vietnamese house, and the deep emotional attachment Vietnamese have to the communal houses of their home villages. In encounters with "others"—the Chinese, French, Japanese, and American overlords who have tried to rule Việt Nam—the Vietnamese absorbed new values, translating them into their own Vietnamese vernacular. Hữu Ngọc shows that the Vietnamese are martial, but not militaristic; they are willing to fight to defend their nation but never forget the anguish that war brings. We see how the Vietnamese have blended their ancient Austronesian cultural heritage and language together with Buddhist traditions brought from India and China, with the value that Confucian ethics from China place on order, harmony, and scholarly learning, and then with the Western influence of humanism and individual liberty. Nevertheless, for Hữu Ngọc, Buddhism remains the "heart" of the Vietnamese village, while Confucian ethics and learning and rites are still its "head." The ancient, quintessentially Vietnamese rites of ancestor veneration that bind a family, clan, and village together and the awe at the legendary powers of the spirits of nature as well as the spirits of national and local heroes are the roots that anchor Việt Nam today.

The second section, "The Four Facets of Vietnamese Culture," illuminates how the ancient Việt (Kinh) ethnic group had its roots in Southeast Asia and defines the Việts' earliest cultural descriptors (e.g., a wet-rice-growing culture and bronze drums) that Việt Nam shares with other Southeast Asian countries. However, Hữu Ngọc specifies the cultural aspects (e.g., matriarchy, mother goddesses, myths, and legends) that are quintessentially Vietnamese. He clarifies the four major facets of Vietnamese culture—the original Southeast Asian roots and the subsequent Indian-Chinese, French, and regional-global branches—and shows how the Southeast Asian base of Vietnamese culture persists today within a dynamism created by tradition and change through acculturation. Central to the features specific to Việt Nam and important in the Việts' preservation of their cultural essence during foreign occupations is the Vietnamese language. Vietnamese has been the mother tongue of the Việt for millennia and, today, is the mother tongue for 85 percent of the country's population, which includes fifty-four ethnic groups. Many nations, particularly former colonies in Africa and Asia, do not have this unifying feature of a common language, which is both ancient and modern.

...

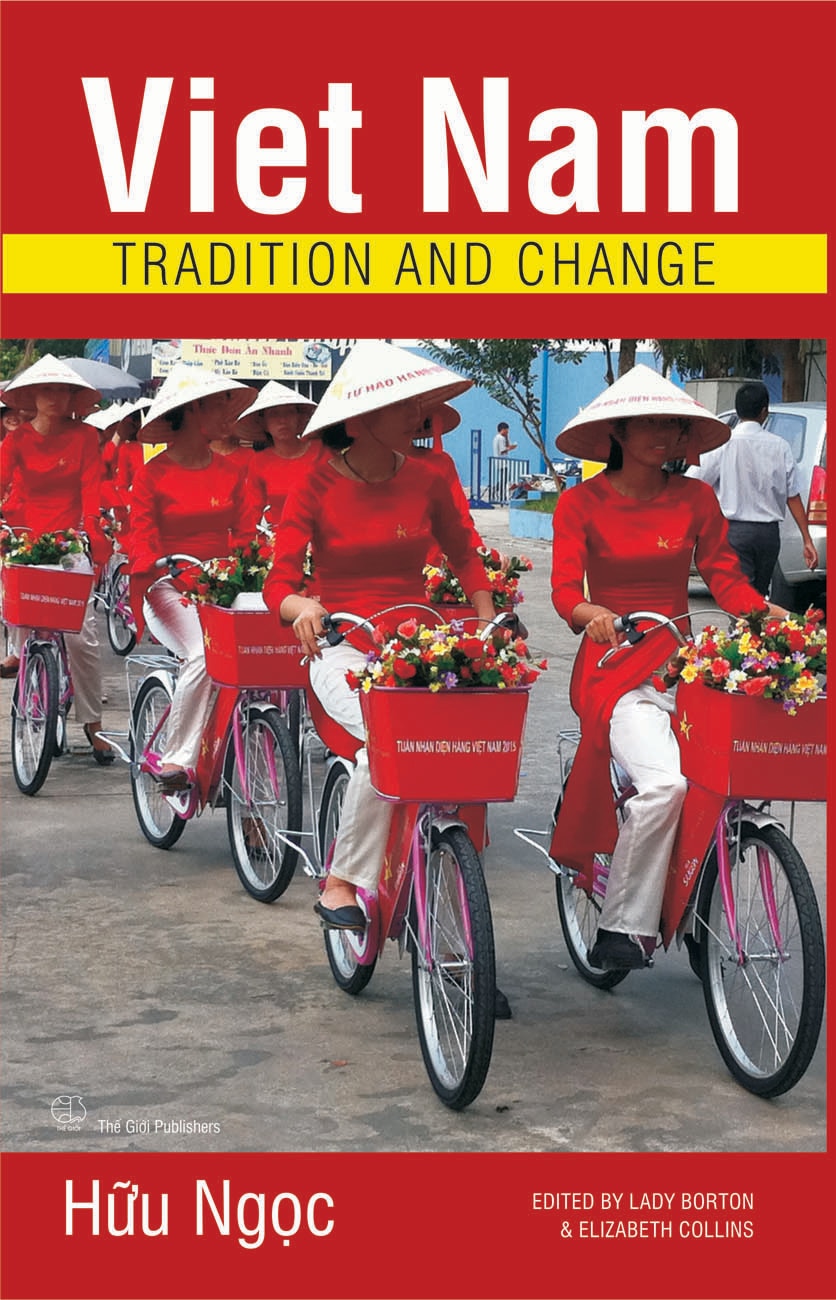

In the book's final two sections, "Vietnamese Women and Change" and "Đổi Mới (Renovation or Renewal) and Globalization," Hữu Ngọc turns his attention to more modern times. Once, teeth lacquering was thought to enhance one's beauty. In the 1930s, the áo dài was created, with French influence; it is now considered traditional Vietnamese dress. In these essays, Hữu Ngọc's subtle commentary suggests that customs and traditions must be thoughtfully assessed for the ways they shape people's lives. Some should be preserved, some reformed, others discarded. Hữu Ngọc reflects on the difficulties confronted by women in the era of Đổi Mới, which began in late 1986, exposing the ways in which Confucian traditions once limited their lives and, now, the new challenges women face. The essays on Đổi Mới consider the problems Việt Nam addresses as it builds an economy linked to global markets, a step that inevitably opens the society once again to outside influences.

Hữu Ngọc argues that national culture "must hold a central position and play the coordinating and regulating role" in economic development and that economic statistics are not an adequate measure of the quality of life of a people. The unfettered expansion of world markets poses a threat to the environment, and there is great danger that the wealth produced will be appropriated by a minority of elites, leaving the mass of people dependent and poor. To shape a different kind of identity, Việt Nam must restore a balance between national traditions fostering patriotism, a strong sense of community, and discipline on one hand and universal values (such as human rights) and the need for economic development on the other.

We find here essays on the impact of a market economy on marriage, divorce, attitudes toward tradition in the "cicada" generation born after 1990, class differences, the traditional village, the value placed on education, and corruption in government. Hữu Ngọc suggests that the traditional family, which is at the heart of national culture, should be modernized, divesting itself of disdain for women. His reflections are nuanced, returning always to the theme, "All tradition is change through acculturation," yet encouraging readers to make their own evaluation of the balance between national values and the values of the market.

Having read these essays, a foreigner sees Việt Nam through new eyes. Written during Đổi Mới, the essays reflect modern times but reach into the rich past of Hữu Ngọc's memory and scholarship. These essays are also a reminder to young Vietnamese and to all of us of the vibrant cultural heritage that distinguishes Việt Nam. The essays can be read in any order. They invite readers to dip in here or there, according to impulse and interest. Taken together and read from beginning to end, they transform one's understanding of Việt Nam, its culture, and its people.

Ngôn ngữ: tiếng Anh

Khổ sách: 14 x 21cm

Số trang: 360 trang