(NLĐO) - The traditional Tet cakes of my hometown are now made in large quantities and sold to tourists. Everyone who eats them praises their beauty and deliciousness, thanks to the heart and soul of the people who made them.

Every year as Tet (Lunar New Year) approaches, no matter how busy I am, I always dedicate a whole day to visiting Loc Yen Ancient Village. It's a National Monument located in Hamlet 4, Tien Canh Commune, Tien Phuoc District, Quang Nam Province; a place not only with many beautiful stone alleys and ancient traditional houses, but also with delicious cakes and sticky rice dishes, passed down through generations with elaborate preparation methods that can't be found anywhere else.

Coming here to admire the scenery, eat ginger-flavored steamed rice cakes and cassava dumplings; buy rice cakes and sticky rice with wine; from my memory, so many dear and warm images of my beloved hometown of Tien Phuoc, where I have lived for more than half my life, come flooding back.

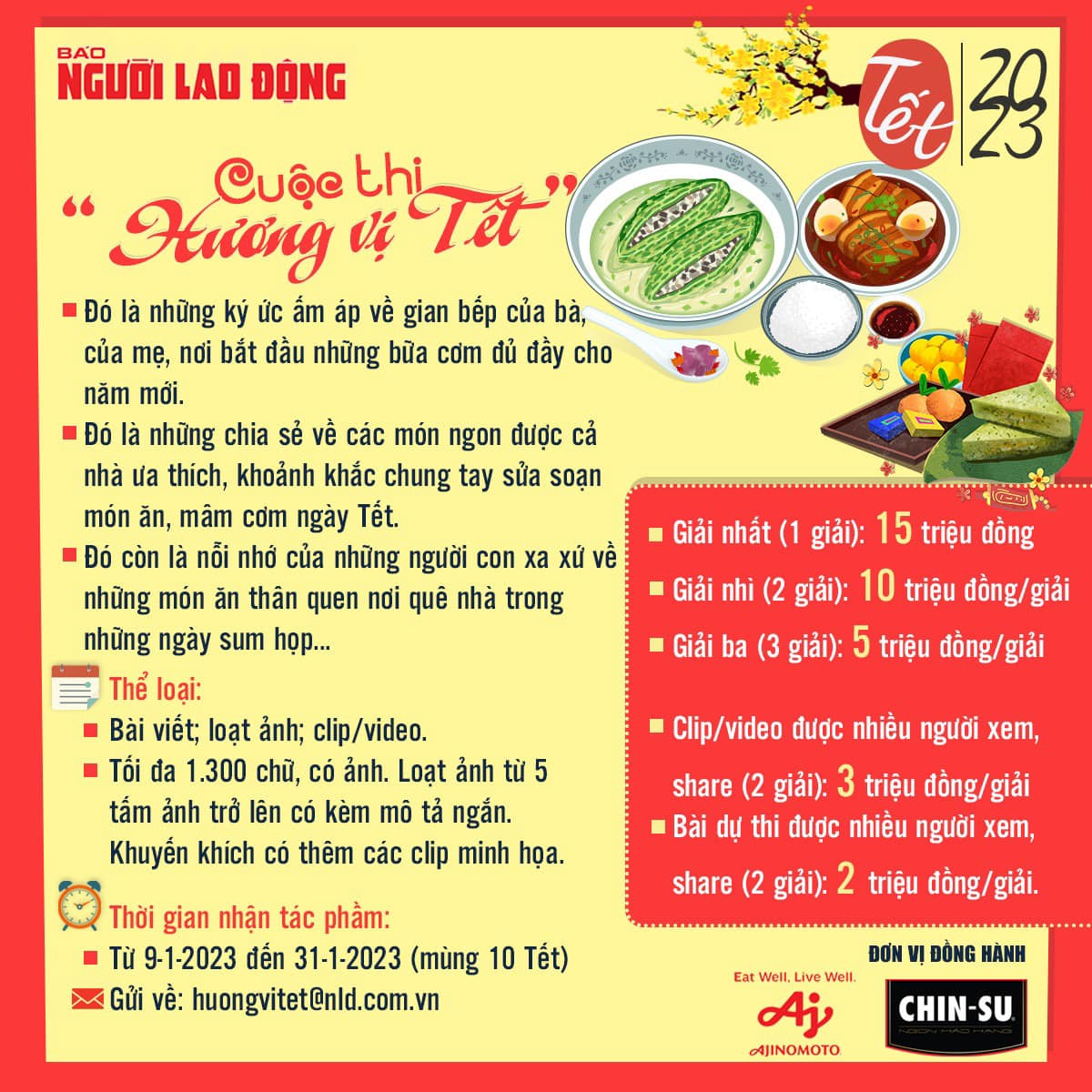

Traditional Tet cakes in Loc Yen ancient village.

Steamed ginger cakes

Around the 24th or 25th of the twelfth lunar month, my mother told me, "Go to the stream and collect some pebbles to make cakes." As soon as I heard that, I grabbed my wicker basket and bamboo tray and went, knowing my mother was preparing to make ginger-flavored cakes. At the stream bank, I selected many large pebbles of various shapes, then took them to a shallow part of the stream and scrubbed and washed them thoroughly. After bringing the pebbles back, I left them in the sun to dry.

To make steamed ginger cakes, my mother chooses fragrant glutinous rice, washes it thoroughly, and soaks it in water for about 7 hours until soft. The soaking water is mixed with the juice of finely grated fresh ginger, then filtered. The rice is ground into flour, and the flour is wrapped in a fine cloth. A heavy stone is then placed on top of the flour overnight to squeeze out all the water.

Next, the dough was kneaded by boiling several fist-sized balls of dough in boiling water until they slightly shriveled; the dough was then broken into pieces, and honey or sugar was added to taste; the boiled dough was mixed with the remaining raw glutinous rice flour and pounded in a large stone mortar. I held the pestle carved from ebony wood and pounded the dough with both hands, while my mother pushed the dough to the center of the mortar. By the time my back was drenched in sweat, the dough had become thick and sticky, and lifting the pestle felt heavy.

My mother rolled the dough into thick sheets, sprinkling a little dry flour to prevent sticking, then cut them into pieces larger than her index finger and dried them in the sun. Once the dough pieces were dry, she soaked them with thinly sliced fresh ginger for a day to give them a fragrant ginger aroma.

Even the baking process was elaborate. My mother placed two pots on a wood-fired stove, skillfully arranging pebbles to create gaps between them, and heated them. When the pebbles were hot, she would place the freshly baked dough pieces into the gaps between the pebbles in the pot, cover it, and steam them. Each piece of dough, upon contact with the hot pebbles, would puff up along the gaps, resembling ginger slices of various shapes. My mother would dip the puffed-up ginger cakes into a syrup made with ginger water, then immediately remove them. I would sit beside her, sprinkle roasted glutinous rice on the outside, and brush a little pink food coloring onto the pointed tips of the cakes, like the small buds on a fresh ginger root. And there you have it, beautiful ginger cakes that were fluffy, rich, sweet, spicy, and fragrant.

Many of the cakes were finished, and my mother would line a large basket with dried palm leaves, arrange the cakes inside, and store them in the rice bin for days, keeping them crisp. At Tet (Vietnamese New Year), serving the ginger cakes on a plate for offerings and guests was truly beautiful. Before enjoying the ginger-baked cake, we children would often admire it for a while before eating. Even after all these years, I still remember the cake with its sweet, rustic flavor of sticky rice and honey; the meaning and sentiment of "spicy ginger, salty salt"; the warmth of the fire; and the loving feelings of family and neighbors.

Cassava dumplings, "B.52" cakes

During Tet, when I returned to Tien Phuoc to revisit the old battlefields and visit relatives in the resistance base area, the uncles and aunts who had fought in my hometown asked, "Do we still make cassava rice dumplings or 'B.52' cakes in our village now?" I replied, "Yes, we do."

Then came the touching stories of Tet holidays during the war, filled with hardship and hunger, when all one could hope for was to see a sticky rice dumpling or a cylindrical rice cake, even if it was wrapped in "scattered cassava" (cassava grown sporadically to avoid detection and destruction by the enemy), or in the scarce bananas found in areas constantly ravaged by chemical weapons and bombs. For me and many of my classmates, on Tet, despite the abundance of delicacies, we still fondly remembered the cassava sticky rice dumpling and the "B.52" cylindrical rice cake, so every year I would make them myself or try to find and buy them.

It wasn't until several years after the reunification of the country that I got to eat ginger-flavored steamed rice cakes, sticky rice cakes, and glutinous rice cakes during Tet, when my family had reclaimed many barren fields to cultivate rice and glutinous rice. My homeland had just gone through a fierce war, so rice and glutinous rice were a dream for many families during Tet. Therefore, in the early years, people used cassava to make the rice cakes.

Rice cakes and "B.52" cakes

On a late afternoon in December, my father would go and harvest cassava, and my mother would peel, wash, remove the core, and grate the cassava into flour. The grater was a piece of aluminum my father cut from an American parachute tube, with many small holes punched in it using a nail; the cassava was grated on the rough side of the grater. The grated cassava flour, mixed with dried cassava flour and a little steamed black beans for the filling, allowed my mother to wrap dozens of rice dumplings.

The whole family stayed up all night pounding the flour to make "B.52" cakes. The cakes were made from boiled cassava pounded in a stone mortar with ripe bananas, wrapped in banana leaves, and tightly tied with bamboo strips like a traditional Vietnamese rice cake (bánh tét). They were then cooked again, and when unwrapped, the cakes were very soft and fragrant.

"B.52" cakes were a food item that my villagers made during the war, taking with them into the deep forests to avoid American B.52 bomber targets. They were made long and large enough for many people to share, hence the humorous name "B.52" cakes. During Tet (Vietnamese New Year) in the war, villagers would make cassava rice cakes and "B.52" cakes to give to soldiers and guerrillas.

Those simple Tet cakes are no longer just a memory. On the last day of the year, I strolled through the market in Tien Ky town and met an old woman carrying a basket of cassava rice cakes to sell. I bought a bunch, still warm; she smiled toothlessly and recounted stories of the old days…

Visiting the ancient village of Loc Yen, returning to my hometown of Tien Son commune, admiring the ginger-flavored steamed rice cake; along with other traditional cakes like banh to, banh no, banh in, sticky rice with gac fruit, warm and loving memories flooded back, and I suddenly felt an unusual warmth in spring.

Source

Comment (0)