The journey of a brick

In 2003, when embarking on the restoration project of the G group of temples and towers in the My Son Sanctuary, the biggest challenge at the time was the availability of bricks for restoration.

War and time have caused most of the G group's temple structures to collapse, with bricks crumbling. The bricks recovered from the excavation are insufficient for reuse in restoration.

Domestic research at that time was only in the initial testing phase. Handcrafted brick production facilities ceased completely nationwide in the 1990s. Industrial bricks readily available on the market were incompatible.

Meanwhile, experts needed a large quantity of bricks for reinforcement, strengthening, filling gaps, and bonding during the restoration process. Bricks, a seemingly simple material, became the first issue that Italian (University of Milano) and Vietnamese (Institute of Conservation of Monuments) experts focused on researching right from the start of the project.

Experts from various fields conducted field research and collected original brick samples for laboratory analysis; simultaneously, experimental production was carried out.

Professor Luigia Binda, head of the engineering and materials group at the University of Milan, recounted: “In 2004, the first experimental production involved 100 bricks. Relying on the skills of the local people, the bricks were made entirely by hand in My Son village, Duy Phu commune. The resulting bricks were of poor quality due to the large amount of clay, insufficient heat, and excessively short firing time.”

We then went to the La Thap Ceramic Factory in Duy Hoa commune. However, the bricks produced were not as expected. Analysis of the bricks revealed that they were not made by hand but using an extrusion machine, resulting in cracks and a significantly different chemical composition compared to the original bricks. The bricks also showed white bubbles on the surface when tested at Tower G5.”

Until 2005, the availability of brick materials remained a major challenge, significantly impacting project progress. That same year, experts visited Mr. Nguyen Qua's production facility in the La Thap ceramics area, Duy Hoa commune, Duy Xuyen district.

Based on the requirements, Mr. Quá observed ancient bricks, independently researched and experimented with production multiple times. As a result, the bricks produced met the basic physical and chemical properties when compared to ancient bricks at Mỹ Sơn.

Achievements in brick restoration

Bricks were brought in by Italian and Vietnamese experts for the restoration of Temple G1 in My Son starting in 2005. They were then used for the restoration of Tower E7 in 2013, and groups A, H, and K from 2017 to 2022.

Mr. Quá also supplied bricks for the restoration of several Champa relics in Binh Thuan and Gia Lai provinces. In 2023, the bricks were even exported to Laos for the restoration of the ancient Wat Phou temple.

From 2005 to the present, four groups of temples and towers (groups G, A, H, and K) with 16 structures and surrounding walls at My Son have been restored, mostly using restored bricks from Mr. Nguyen Qua's workshop. The remainder consists of original bricks recovered from the excavation process.

The original bricks are reused to the maximum extent. Restoration bricks are interspersed with the original bricks. Most areas requiring bonding, reinforcement, or strengthening use new bricks. At Temple G1, bricks from Mr. Quá's kiln were used, and after nearly 20 years, the quality of the bricks remains essentially assured.

Architect Mara Landoni, who has over 20 years of experience restoring brick relics at My Son, stated: "Initially, the newly produced bricks were of substandard quality and not compatible with the original materials, but later, the quality of the bricks improved."

The new bricks used for restoration in group G are still in fairly good condition and quite compatible after 20 years. A few small areas where salt previously appeared, such as in towers G3 and G4 of group G, have since disappeared due to erosion by rainwater.

According to Danve D. Sandu, Assistant Director of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI): “We are taking samples of new bricks for analysis and comparison of their physical and chemical properties with the original bricks at the site we are restoring.”

The restored bricks from Mr. Nguyen Qua's fine art ceramics production facility are of guaranteed quality and quite stable. We not only used these bricks for restoration at My Son Sanctuary but also for restoration at Wat Phou, Laos in 2023 due to the similarities in brick materials between the two sites.”

Risk of a shortage of bricks for restoration.

Since the end of May, Mr. Nguyen Qua's brick production facility has temporarily ceased operations. Explaining the suspension, Mr. Le Van Hung, Chairman of the Duy Hoa Commune People's Committee, Duy Xuyen District, stated: "Because Mr. Nguyen Qua's brick-making facility is located in a residential area and the brick-making process is still done manually, it negatively impacts the environment. If he wishes to continue with the manual brick-making process, Mr. Qua should submit a petition to the Duy Xuyen District People's Committee for consideration."

Meanwhile, Mr. Nguyen Qua argued that, given his age, finding a new location to build a kiln and workshop would be difficult. “Working far from home would be very inconvenient, and the cost of manual labor would increase. I could send bricks to other facilities for firing. However, none of them fire bricks using traditional manual methods; most now use tunnel kilns. And I'm not sure about the quality assurance of tunnel kilns.”

According to information from the Indian Embassy in Vietnam, the Indian government is expected to continue its interest in restoring several Champa relics in central Vietnam, including the E and F temple groups of the My Son Sanctuary.

"Furthermore, if the L project at My Son is implemented, new bricks will also be needed. Therefore, the quantity and quality of bricks required for restoration in the coming period must be sufficient. However, given the current inability of Mr. Nguyen Qua's facility to produce bricks, the risk of a shortage of bricks for restoration is clearly evident."

"The lesson learned from the Group G restoration project 20 years ago is that without bricks, the restoration work cannot proceed, affecting the project's progress, or even forcing the project to stop," added Mr. Nguyen Cong Khiet, Director of the My Son Temple Complex Management Board.

The newly restored brick product is one of the research results from a tripartite cooperation project between UNESCO, Italy, and Vietnam from 2003 to 2013. To achieve this result, in addition to the research of experts, the skill and experience of artisan Nguyen Qua were indispensable.

Nearly 20 years have passed, enough time for the craft of making restoration bricks to become a local handicraft. And this craft, of course, is essential to maintain if we want to preserve the ancient Champa relics. Moreover, it has become a rare and valuable craft of the Duy Xuyen region.

The fact that Mr. Nguyen Qua's brick factory has ceased production, while no replacement facility has yet been established, raises questions about the future supply of bricks for the restoration of ancient Champa relics.

Mr. Nguyen Qua is a ceramic artist with over 50 years of experience, having received training in ceramic techniques and design in Guangdong, China. He produces many fine art ceramic products for both domestic and international markets, including Japan and the Netherlands.

“When the experts came to discuss making bricks for restoration, I thought about it a lot. They requested a similar method to making ancient bricks at My Son, using traditional methods. Although I had never made bricks for restoration before, I thought the basic steps were similar to pottery making. The important thing is ‘the best material, the second best firing, the third best shape, and the fourth best painting.’”

"Each brick is meticulously crafted like a piece of pottery. The most difficult step is firing because the bricks are large and thick. After the bricks are completely dried, they are fired, a process that takes up to two weeks. The main fuel is firewood. When firing, it's crucial to monitor the kiln fire; if it's too hot or too cold, the bricks cannot be used for restoration," said Mr. Nguyen Qua.

Source

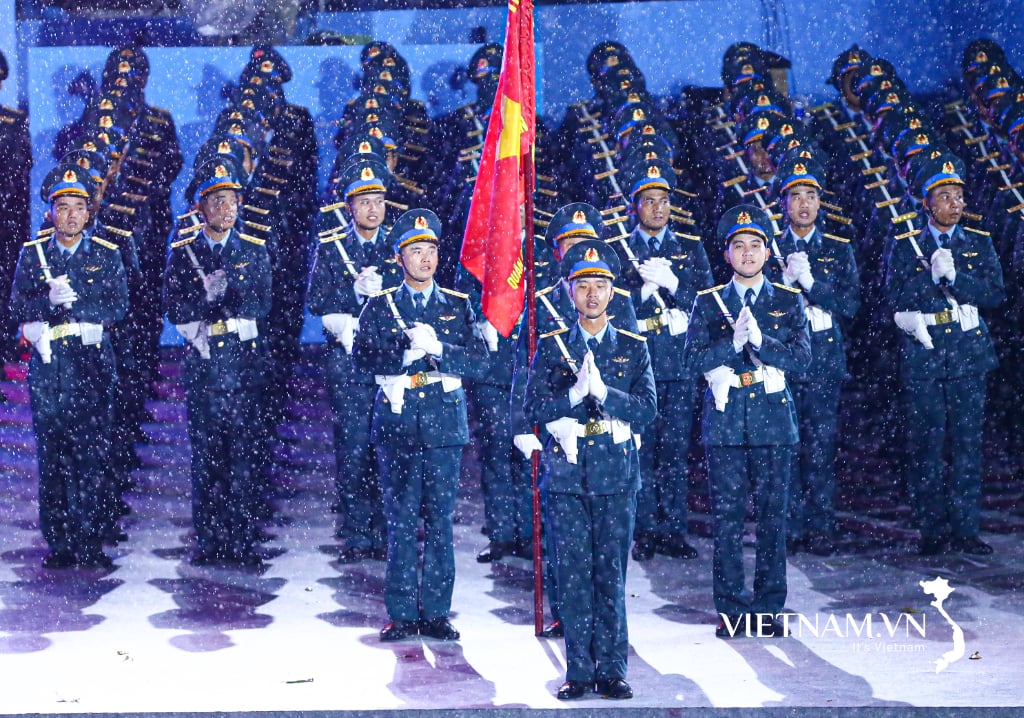

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam working with Ambassadors and Heads of Vietnamese representative offices abroad attending the 14th National Congress of the Party](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F25%2F1769334314499_image.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)