According to Vietnamese historical records, before the Ly Dynasty, only major events were recorded, sometimes only one event a year, so the records are quite brief. Only from the Tran Dynasty onwards do we find instances of the court holding a royal court ceremony on the very day of the Lunar New Year (the first day of Tet), such as in the 8th year of Nguyen Phong (1258), when the people of Dai Viet had just repelled the Mongol army during their first invasion of our country, and this event took place on the Lunar New Year. "Dai Viet History Chronicle" writes: "In the spring, in the first month, on the first day, the king presided over the main hall, allowing all officials to attend. The people lived in peace as before."

The story of the king hosting a banquet for civil and military officials was first recorded in the "Complete History" during the early Le Dynasty, in the reign of King Le Thai Tong, in the year of the Rabbit, the second year of the Thieu Binh era (1435). This historical work states: "The king held a five-day banquet for civil and military officials inside and outside the kingdom, and distributed money to civil and military officials holding positions outside the kingdom according to their different ranks." However, the event took place after the fourth day of Tet (Lunar New Year), because on the fourth day, the Le court received envoys from Laos, San Mac and Sat Mau, who "brought gold and silver wine and two elephants as tribute."

In the year of Ky Ty, the 7th year of the Thai Hoa era, during the reign of King Le Nhan Tong (1449), the "Complete Book" continues to record that: "In the spring, in the first month, a banquet was held for the officials. Music and dances were performed to defeat the Ngo army." In the year of Binh Ty, the 3rd year of the Dien Ninh era (1456), the event is recorded again, with a clear date: the 3rd day of Tet: "A grand banquet was held for the officials, Lang Son King (Le) Nghi Dan attended the banquet." The appearance of Le Nghi Dan is recorded in detail because later, in the 6th year of Dien Ninh (1459), Le Nghi Dan assassinated King Le Nhan Tong to ascend the throne for himself.

King Le Thanh Tong probably disliked banquets, so throughout his reign, there is no record of him granting banquets to his officials. Even in the 14th year of Hong Duc (1483), the first entry in the historical records of that year states: "In the spring, on the 13th day of the first month, banquets were forbidden for officials to prepare elaborate feasts and usurp the ceremonial rites!"

During the Le Dynasty's restoration period, on the morning of the main day of the Lunar New Year, Lord Trinh would lead his civil and military officials to offer congratulations to King Le on his birthday. Afterwards, the main New Year celebrations took place at Lord Trinh's palace, including a banquet hosted by the Lord for his officials. Besides enjoying the feast, the officials were also rewarded with money by the Lord, in the form of "precious coins" (each official had to have 600 coins, while the common people used "lower-grade coins," each receiving only 360 coins). The reward for a First-Rank official was 5 precious coins; Second-Rank received 4 coins; Third-Rank received 3 coins; Fourth-Rank received 2 coins; Sixth and Seventh-Rank received 1.5 coins; Eighth and Ninth-Rank officials and civil and military officials such as Deputy Chief, Assistant Chief, and Chief of Staff received 1 coin...

In Dang Trong, the regulation of offering banquets to officials began during the time of Lord Nguyen Anh, but it was initially in the most important ceremony, the Lord's birthday. The Nguyen Dynasty's historical record "Dai Nam Thuc Luc" states that in the spring of the year Tan Hoi (1791), in the first month, the day of the Holy Birth (the 15th) was taken as the Van Tho festival. In this ceremony, after the ceremony of paying respects at the Thai Mieu temple and greeting the Queen Mother, the officials wished the Lord a long life, and there was an item "Allowing officials to enter the Phuong Dien (square-shaped hall) to eat a banquet. From then on, it became a regular custom every year".

The custom of holding a banquet for officials on Lunar New Year's Day in the Nguyen Dynasty probably began during the reign of Emperor Minh Mang. The Nguyen Dynasty's historical records mention an edict from the 7th year of Minh Mang's reign (1826) regarding rewards for officials on Lunar New Year's Day: “The Lunar New Year is approaching, and I will celebrate with you, my ministers. On that day, I will order a banquet and reward officials according to their rank. Princes and dukes will each receive 20 taels; civil and military officials of the First Rank will each receive 12 taels; those of the Second Rank will receive 10 taels; those of the Third Rank will receive 4 taels; those of the Fourth Rank will receive 3 taels… Imperial guards, captains, squad leaders, and commanders… will each receive 1 tael and will all be invited to the banquet.”

The custom of holding banquets for officials continued during major holidays and festivals, including Lunar New Year, Longevity Day, Dragon Boat Festival (the 5th day of the 5th lunar month), Mid-Autumn Festival (the 15th day of the 8th lunar month), and the celebrations of the Empress Dowager's 50th, 60th, and 70th birthdays. The practice of holding banquets was only suspended during periods of national mourning, when all banquet activities were abolished. For example, after King Gia Long's death, King Minh Mạng ascended the throne. In the year Canh Thin, the first year of the Minh Mạng reign (1820), after bestowing the posthumous title of Thừa Thiên Cao Hoàng hậu, the king issued a decree replacing the banquet for officials in the capital and outside the capital.

The king's decree to the officials read: "Upon ascending the throne, it is necessary to show favor to all, to feast with the ministers, to celebrate the wise king and virtuous ministers, and to ensure harmony between the upper and lower ranks... The usual practice of showing respect and reciprocity has been completed, but the music is still silent, the swords and bows are not yet cool, and I am still grieving; how can this be the time for a joyful banquet between king and ministers! The ritual cannot be overstepped, and the matter cannot be neglected. Therefore, silver will be used instead of the banquet according to different ranks. (First-rank officials receive 20 taels of silver; principal First-rank officials receive 15 taels; subordinate First-rank officials receive 10 taels; principal Second-rank officials receive 8 taels; subordinate Second-rank officials receive 6 taels; principal Third-rank officials receive 3 taels; subordinate Fourth-rank officials receive 2 taels. Officials in the capital from Fourth-rank upwards, and officials outside the capital from Third-rank upwards)."

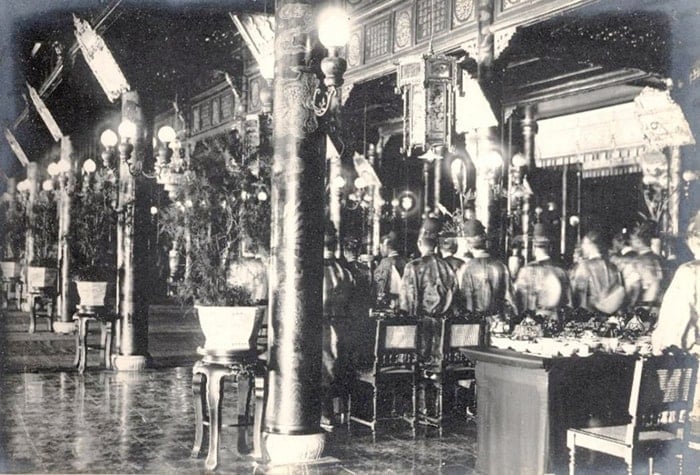

The banquets of the Nguyen dynasty for officials were usually held in the Can Chanh Palace. In the early years of the Minh Mang reign, the court even built a trellis outside the palace to set up tables for officials to sit at the banquet. Later, the king instructed the Ministry of Rites: "I think that the banquets of previous emperors were mostly held in the palace. Now, the palace is spacious, so why bother building a tent and wasting manpower? From now on, on celebratory occasions, banquets can be held in the palace."

Details regarding seating arrangements during banquets in the Can Chanh Palace are recorded in the "Dai Nam Thuc Luc" (Chronicles of Dai Nam), in the 18th year of Minh Mang (1837), according to a petition from the Ministry of Rites: "The two side halls on the left and right of the Can Chanh Palace, each with five bays, are all paved with eight-panel planks and covered with mats. The central bay on the left has a red lacquered altar for stamping the national seal, while the left and right bays are for officials to sit. The Lang Trung, Khoa Dao, Vien Ngoai Lang, and even the clerks all sit on planks placed close to the ground. Considering the hierarchy of the court, it is related to the perception of everyone. Lang Trung, Vien Ngoai, and Khoa Dao are officials of the Fourth and Fifth ranks in the capital; now, sitting together with clerks in the office is not considered elegant. Therefore, we request that the rows of planks in the central bay and on the left and right sides be raised up to the brick steps to distinguish their height from the two rows of planks on the left and right. The central bay will have the red lacquered altar for stamping the seal, and the rest will be for the emperor's mats to sit on." "The officials and dukes sat in the left and right chambers, while the Langzhong, Yuanwai, and Khoadao sat in the left and right chambers. Outside, from the Chief Clerk, Secretary, and Eighth and Ninth-rank clerks, everyone else sat on mats on the ground."

Besides banquets and rewards during festivals and holidays, King Minh Mạng also stipulated that officials be given silk according to their rank. Regarding those allowed to attend banquets during festivals and holidays, the "Dai Nam Thuc Luc" states that in the 16th year of Minh Mạng's reign (1835), the king instructed the Ministry of Rites: "According to the old regulations, every year on the Lunar New Year, banquets and rewards are given to civil and military officials from the fifth rank and above. On the Longevity Festival, banquets are given to civil and military officials from the fifth rank and above. On the Dragon Boat Festival, the plowing ceremony is held, banquets are given to civil officials from the Lang Trung and military officials from the Pho Vu Uy and above. Furthermore, all cabinet members are allowed to attend. This is a special favor. However, considering the joyous occasions of banquets and rewards, there is a connection to ceremonial procedures. In the court, regulations must be established according to rank. Is it appropriate to allow those who are not worthy to attend to participate?"

Therefore, it is hereby stipulated: All ceremonies shall be conducted according to established practice, and participation shall be based on rank. However, officials of the Cabinet, the Privy Council, and the acting officials of the Ministry of Rites, departments, and bureaus, and those holding official positions within the Censorate, shall not participate in any ceremony for which their original rank is not sufficient.”

Later, in the 18th year of Minh Mạng (1837), on the first day of the Lunar New Year, during the Empress Dowager's celebration that year: "The civil and military officials in the capital, from the fifth rank upwards, along with the annual officials from the localities, all came together, were given a feast and rewarded according to their rank."

Officials in the capital on the list of those allowed to attend the banquet, if they had to go on official business, would also receive compensation. A royal decree issued in 1837 stated: “All civil and military officials in the capital, from the seventh-rank official in charge of affairs, and military officials from the sixth-rank in command of troops upwards, who are unable to attend the banquet on the celebratory day, will be rewarded. Those appointed by the Ministry, or those on official business who have completed their leave but have not yet returned to the capital, will receive two months' salary according to their rank. Those who return for mourning, whose leave has expired, or who are ill at their residence will receive one month's salary.”

According to the book "Kham Dinh Dai Nam Hoi Dien Su Le" (Imperial Compilation of the Great Nam Dynasty's Regulations), the royal banquets included offerings at ancestral temples and shrines during important holidays such as Tet Nguyen Dan (Lunar New Year), other festivals, banquets for officials or Chinese envoys, and banquets for newly appointed doctoral graduates. These were the responsibility of the Quang Loc Tu (Imperial Court of the Imperial Household), which arranged and inspected the banquets, while the Ly Thien and Thuong Thien departments directly handled the cooking. The book states that the banquets were divided into different categories. The grand banquet consisted of 161 dishes, the jade banquet had 30 plates, the precious banquet had 50 dishes, and the dessert banquet had 12 dishes. However, the details of the dishes in the royal banquets have not been recorded in detail to this day.

Nevertheless, judging from the royal cuisine that has been passed down to this day, it's clear that a royal feast would undoubtedly be extravagant, delicious, and also quite... expensive.

LA (compiled)Source: https://baohaiduong.vn/co-vua-ban-ngay-tet-403978.html

![[Image] A dreamy "livable city" under pink clouds](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/24/1771930060937_tp4-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Head of the Central Propaganda and Mass Mobilization Department visits and congratulates the Ministry of Health and the Military Traditional Medicine Institute.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/24/1771938483290_img-2682-3562-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] White pear blossoms bloom across the border of Pho Bang](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/24/1771927665653_a8-8280-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)