Tet customs reflect many cultural attributes of the Vietnamese people in a predominantly agricultural society. Many of these customs have been "inherited" to this day. If we filter out prejudices stemming from cultural and religious differences, the records of Vietnamese Tet customs recorded by Westerners possess a unique, captivating quality, and offer interesting discoveries due to certain distances between the two cultures...

Year-end debts

Infiltrating both Northern and Southern Vietnam to spread Christianity in the early 17th century, the missionary Alexandre de Rhodes observed the customs and rituals of the Lunar New Year with considerable prejudice stemming from a different religious and cultural tradition. However, he also noticed another subtle aspect: hidden behind the bustling scenes of the New Year was a sense of anxiety among the Annamese people in general.

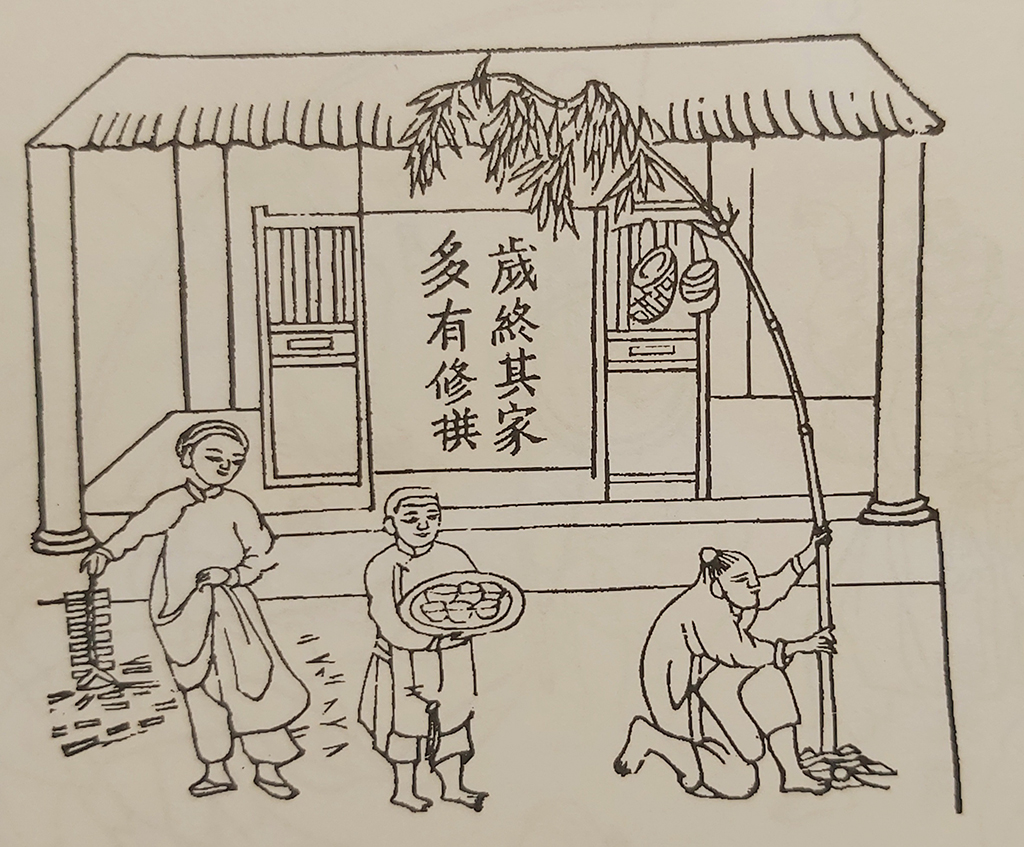

A family preparing to celebrate the traditional Lunar New Year. Woodcut by Henri Oger (made in 1908-1909)

Since ancient times, Tet (Lunar New Year) has been a source of dread for the poor, as it marks a milestone in their arduous year of earning a living. Farmers must pay land rent, small traders must settle their debts, and most importantly, everyone anxiously faces the first tax payment of the year.

In his book *History of the Kingdom of Tonkin* (first published in Italian in 1652), Father Rhodes wrote about the psychological obsession with debt, the fear of creditors coming to demand payment at the beginning of the year, and the possibility of insulting or offending deceased parents and ancestors: "They still worry about paying off debts before the end of the year for a superstitious reason; they fear that creditors will come to demand payment on the first day of Tet, and of course, they will have to pay on that day, which they consider extremely harmful and an ominous sign" (translated by Hong Nhue Nguyen Khac Xuyen).

In the book, the word "debt" is mentioned frequently in the chapter discussing the customs observed by people in Northern Vietnam on the last and first days of the year. It's evident that this obsession is linked to sacred connections within traditional ancestral worship, specifically the need to ensure that worldly problems don't have spiritual repercussions for the deceased.

The missionary's explanation of the New Year's pole in Northern Vietnam seems rather simplistic, but broadly speaking, it also reveals the frustration caused by debt extending to the afterlife, a phenomenon he likely heard during his missionary work: "Others with responsibilities in the household, such as the head of the family, would at the end of the year erect a long pole near the door, extending beyond the roof, with a basket or bag perforated with many holes and filled with gold and silver paper money hanging at the top. They… imagined that their parents had passed away, and at the end of the year they might be in need of gold or silver to pay off debts. Another custom was that no one, from the rich to the poor, would default on their debts beyond the due date, except in cases where they were unable to repay. It would be commendable if they did not do this out of superstition, as they often did, fearing that the creditor would be angered and reprimand their ancestors, causing the ancestors to resent their descendants and heirs."

Afraid of being harmed by evil spirits.

There is a custom which, according to the missionary Alexandre de Rhodes, author of *Eight-Day Sermons*, *Journeys and Missions*, and the *Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin Dictionary*, is "superstitious," stemming from the fear of evil spirits appearing during the transition from the old year to the new: "There is an ancient but strange custom still observed throughout the Northern region, that elderly people, both men and women, at the end of the year, fearfully hide in temples as a refuge to avoid the evil forces they call Vo Tuan (…). Therefore, these unfortunate people, for the last three or four days of the year, take refuge inside temples, day and night, not daring to go out until the first day of Tet, only returning home, because they believe that the power of evil spirits that harm and are enemies of the elderly has ended."

Hanoi's Old Quarter during Tet (Lunar New Year) in 1915

The custom of erecting a New Year's pole to ward off evil spirits from entering homes exists, but the idea that people "take refuge in temples day and night, not daring to go out until the first day of Tet before returning home" is perhaps an interpretation related to the custom of visiting temples on New Year's Eve and the first day of the Lunar New Year (!?).

In his writings, from the perspective of a missionary with a different faith tradition, Father Alexandre de Rhodes viewed the Vietnamese religious practices during the first three days of the year as superstitious: "On the first day of the year, according to the customs of non-believers, there are often superstitious rituals and offerings during the three days of Tet."

However, in the same book, he recounted a very solemn plowing ceremony. On the 3rd day of the lunar month, the king, seated on a magnificent throne, carried in a palanquin, walked through the capital city of Kẻ Chợ amidst the welcoming and praise of his subjects. The plowing ceremony was held in a field a mile from the capital: "His Majesty (the king) stepped down from the throne, and after reciting prayers and solemnly bowing to Heaven, he took the plow handle, which was decorated with many colors and elaborate carvings, plowed for a few minutes, and opened a furrow in the field, to teach the people how to work tirelessly and care for the land" (Chapter 3, How the People of the North Worship Their King? ).

The traditional Tet (Lunar New Year) celebrations in the late 1620s, as recorded by the missionary Alexandre de Rhodes, reflect, to some extent, the sentiments of the purely agricultural population of Vietnam in the feudal society of the past. (to be continued)

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the Conference on the Implementation of Tasks for 2026 of the Industry and Trade Sector](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F19%2F1766159500458_ndo_br_shared31-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)