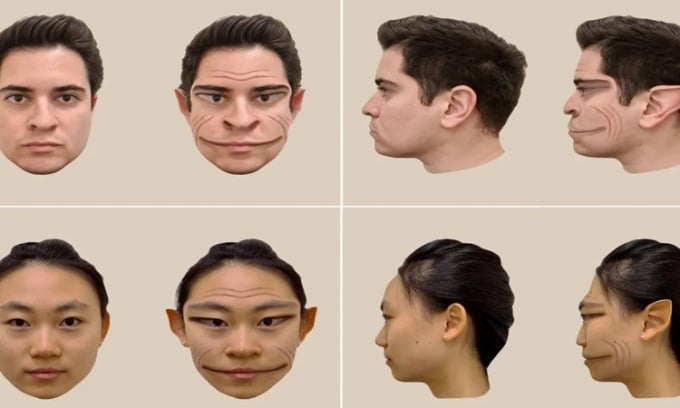

For the first time, scientists have recreated what patients with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO) look at other people's faces.

Sharrah's face was distorted when she looked at people. Photo: Antônio Mello

One winter morning three years ago, Victor Sharrah woke up and saw his roommate go into the bathroom. However, when Sharrah looked at his friend's face, he was horrified by the distorted features, like a "demon face." In Sharrah's eyes, his friend's mouth and eyes were elongated, his ears pointed, and there were deep wrinkles on his forehead. In reality, his friend's face hadn't changed; instead, a syndrome had altered how Sharrah perceived it. He was terrified because the same thing happened when he looked at other people's faces.

"I tried to explain to my roommate what I was seeing, and he thought I was crazy," Sharrah shared. "Imagine waking up one morning and suddenly everyone in the world looks like a character from a horror movie."

Sharrah, now 59 years old and living in Clarksville, Tennessee, was diagnosed with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO), an extremely rare neurological disorder that causes a person's face to appear distorted. Since 1904, fewer than 100 cases have been recorded, and many doctors have never even heard of the condition. But Sharrah's case could raise awareness of this mysterious syndrome and provide insight into the lives of those with PMO. For the first time, researchers were able to create digital simulations of what a distorted face looks like for someone with PMO like Sharrah, and published their findings in The Lancet on March 23, according to the Smithsonian .

Sharrah's face only distorted when he looked directly at people. When he looked at faces in photos or on a computer screen, the images appeared perfectly normal. This difference allowed researchers to use photo editing software to recreate what Sharrah saw. They did this by showing Sharrah a photo of a person's face while that person stood in the same room with him. As he described the differences between the photo and the real person, the research team adjusted the photo until it matched Sharrah's description.

Symptoms of PMO vary considerably from person to person. Faces may appear swollen, pale, or have bizarre patterns, and distinctive features may shift to different areas of the face. When looking in a mirror, the patient's own face may appear distorted. So, while digitally altered images represent what Sharrah sees when looking at people's faces, they may not match the experience of other PMO patients. However, the images are useful for people to understand the type of distortion patients might see, according to Jason Barton, a neuroscientist at the University of British Columbia in Canada, who was not involved in the study.

Doctors often confuse PMO with mental health syndromes such as schizophrenia or psychosis. While there is some overlap in symptoms, a major difference is that patients with PMO don't think the world is actually distorted; they are aware that their perspective is different, according to study co-author Antônio Mello, a cognitive psychologist and neuroscientist at Dartmouth University.

"Many people are hesitant to mention their symptoms because they fear others will think the deformities are a sign of a mental disorder," says Brad Duchaine, a psychologist and brain scientist at Dartmouth University. For many, PMO symptoms disappear within a few days or weeks. But for some, like Sharrah, they can last for years.

Researchers are still unsure what causes PMO, although they suspect it results from problems in the part of the brain that processes facial images. Some patients develop PMO after a stroke, infectious disease, tumor, or head injury, while others develop it as a temporary illness with no clear explanation.

For Sharrah, four months before the symptoms began, he suffered carbon monoxide poisoning. More than a decade before that, he sustained a severe head injury when he fell backward and hit his head on the floor. However, in his case, adjusting the lighting to a specific green tone helps him see his true face.

Researchers hope the new paper will help doctors accurately diagnose PMO. They also hope the study's findings will help PMO patients feel less alone.

An Khang (According to Smithsonian )

Source link

Comment (0)