However, education experts and parents argue that a lack of integration can put children at a significant disadvantage both academically and emotionally.

Discrimination model

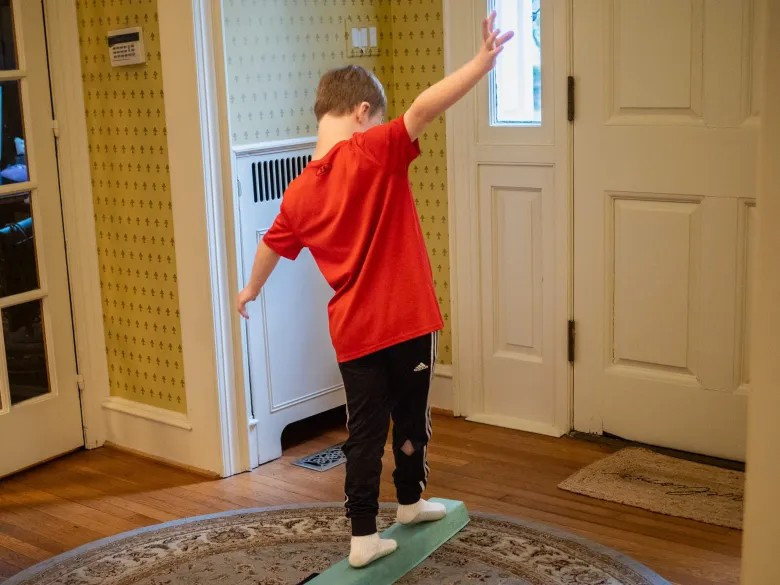

Terri Joyce believed her son deserved to attend a preschool class with both typically developing and disabled children. At age four, he happily participated in a program designed for typically developing children, without any special support.

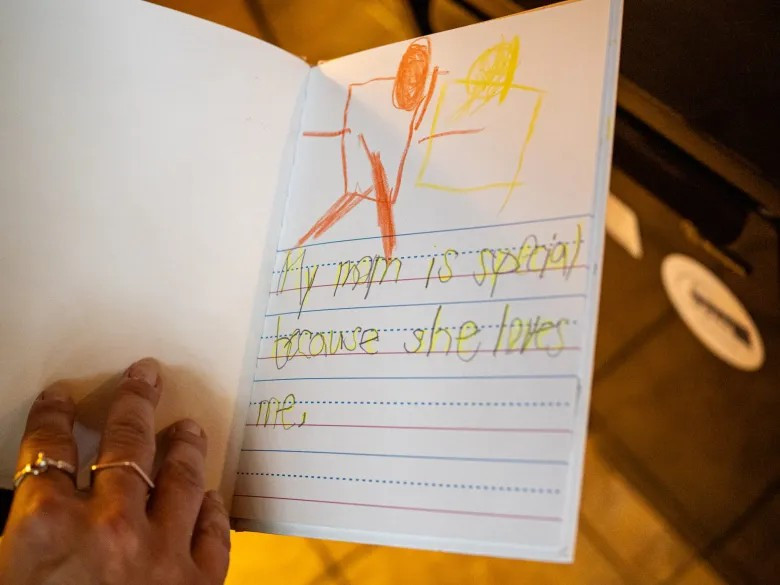

Like other children his age, Joyce's son, who has Down syndrome, learned about drawing and enjoyed sitting on the mat listening to his teacher read. His speech delay didn't prevent him from making friends and playing with children of different abilities. In the summer, he participated in the same program all day and often greeted his mother with bright smiles when school ended.

However, when Joyce met with district administrators before kindergarten, they told her that her son would have to attend a class exclusively for students with disabilities. “They completely refused to consider inclusive education for children with disabilities. They said my son needed special instruction,” Joyce said. However, Joyce found that attending a separate class discouraged her son.

Under federal law, students with disabilities—those who have faced exclusion from public schools—have the right to learn alongside their typically developing peers “to the fullest extent possible.” This includes the right to support and assistance.

From there, they can continue their education in mainstream classrooms. According to federal data, the majority of students with disabilities in New Jersey are not integrated with typically developing children. They spend most of their day attending separate classes.

Many parents report that children with disabilities have virtually no access to mainstream education. Only 49% of children with disabilities aged 6 to 7 in the state spend most of their day in mainstream classrooms. In some New Jersey counties, this rate is as low as 10% for younger students.

Overall, approximately 45% of students with disabilities of all ages are primarily enrolled in mainstream school classes, compared to 68% nationally. For more than three decades, the state has faced lawsuits and federal scrutiny over its model, which is considered to be unnecessarily discriminatory against students with disabilities.

The right to inclusion

Surrounded mostly by children who struggled with communication, Terri Joyce's son's speech development was limited. He wasn't exposed to what his peers were learning in mainstream education, such as science and social studies.

Joyce attempted to mediate with Cinnaminson County, but without success. Ultimately, the parent hired a lawyer, filed a legal lawsuit with the state, and successfully secured her son's place in a co-educational class the following year.

New Jersey is known nationally as a leader in public education. However, the state's administrative system has led to varying rates of inclusion across counties. “Mindset is the biggest barrier. There are educators, parents, administrators, and doctors who genuinely believe that separation is better for typically developing children and children with disabilities.”

"With over 600 counties, local oversight makes the change process more difficult," said Michele Gardner, CEO of All In for Inclusive Education and former Berkeley Heights County administrator for 15 years.

Experts say that allowing students with disabilities to participate in the general education program is easy. This measure is also believed to bring great benefits. Many studies have shown that both normal and disabled students, especially young children, can benefit from inclusion.

Young children also learn by observing each other. Meanwhile, parents worry that rejecting students with disabilities could cause long-term harm to their academic and emotional development. Around the world , inclusion is considered a human right that helps all children develop compassion and prepare them for society.

Parents in New Jersey report that young students are often placed in separate classes based on diagnoses, rather than being assessed for their actual support needs. Christine Ashby, a professor of special education at Syracuse University, stated, "We're seeing a trend where, even at a younger age, students are being placed in separate schools and never really begin to engage in inclusive experiences."

These students then tend to be in separate, closed classrooms. Here, they may receive individualized instruction along with peers with disabilities, but may be less prepared for life after high school.

For Terri Joyce, her struggle to get her son into primary school has proven worthwhile. It took him some time to adjust, but with the help of an assistant, he settled in and is now in first grade, thriving alongside his classmates. “My son’s speaking has improved. He loves school. He has friends and gets invited to birthday parties,” the parent shared.

In this context, the New Jersey Department of Education says it is working with schools across the state to improve the frequency of inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream education classrooms through training, technical support, and inclusion promotion programs.

“All placement decisions must be made on an individual basis. There are no single standards or outcomes that can apply to every district, school, or student,” said Laura Fredrick, the Department’s Director of Communications.

According to Fredrick, counties that fail to meet the state's goals for increased inclusion may face closer scrutiny. In Cinnaminson, schools said they would work with parents to make decisions about classroom arrangements.

“We do our best to place students in the appropriate general education classes so that they can have the most comprehensive educational experience possible,” stated Stephen Cappello, Superintendent of Cinnaminson Township Public Schools.

According to Professor Douglas Fuchs, a special education professor at Vanderbilt University, most students with disabilities do not require highly intensive instruction. Educators say that intensive instruction can be provided without isolating the children in a separate environment for much of the time.

“Should we isolate young people to provide them with a service, or can we bring them in and provide the same or better service? We believe it is possible to integrate children,” said André Spencer, Superintendent of Teaneck Public Schools.

For Terri Joyce's son, attending the general education class meant access to a comprehensive education, including social studies. Lessons on citizenship inspired him.

"My son is very interested in learning about Martin Luther King. He spends hours watching videos of his speeches on YouTube," shared parent Joyce.

Like other students with disabilities, Joyce's son undergoes annual assessments. This means his integration into mainstream school life is not guaranteed in the coming years. However, Joyce's efforts to ensure her son's integration extend beyond academics.

The boy joined the football team and rode the school bus. Other children recognized him and greeted him at the grocery store. “That’s far more beneficial than just studying and being in class. Being in school means my child is more involved in life, the community, and is valued,” this parent expressed.

Some studies show that even students with severe disabilities can learn alongside their peers in general education with the help of teachers or professional assistants. Inclusion does not harm either typically developing or disabled children. Meanwhile, many experts point out that a separate classroom environment may be suitable for some children. However, children may fall behind without specialized support in general education classrooms.

Source: https://giaoducthoidai.vn/xoa-bo-rao-can-post737204.html

![[Photo] The General Secretary attends the groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of the Truong Ha Primary and Secondary Boarding School.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F28%2F1769604498277_vna-potal-tong-bi-thu-du-le-khoi-cong-xay-dung-cong-trinh-truong-pho-thong-noi-tru-tieu-hoc-va-trung-hoc-co-so-truong-ha-8556822-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Commemorating the unwavering friendship between Vietnam and Laos](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F27%2F1769518372051_ndo_br_1-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with former leaders of the National Assembly from various periods.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F28%2F1769601014034_anh-man-hinh-2026-01-28-luc-18-50-04.png&w=3840&q=75)

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 3] Ultra-thin rice paper takes off.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F28%2F1769562783429_004-194121_651-081010.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 2] Hoa Thanh incense village glows red.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F27%2F1769480573807_505139049_683408031333867_2820052735775418136_n-180643_808-092229.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 1] Ba Den custard apples in their 'golden season'](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F26%2F1769417540049_03-174213_554-154843.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)