Research based on the rare accident of a railroad construction worker in the US who had an iron rod pierced through his skull laid the foundation for the birth of modern neuroscience .

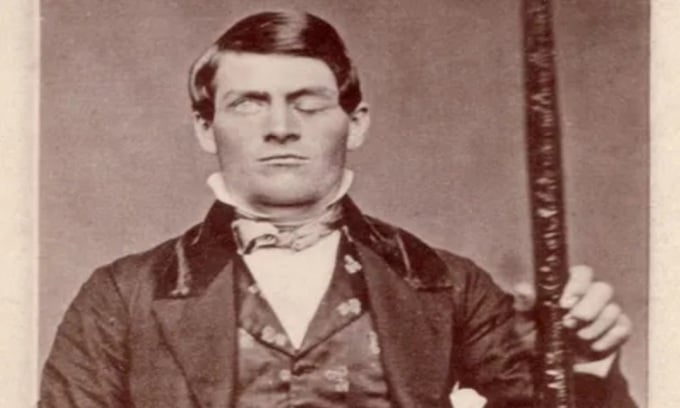

Phineas P. Gage after the accident with the iron bar. Photo: Wikimedia

When an explosion sent a steel bar straight through the forehead of railroad foreman Phineas P. Gage in New Hampshire, no one expected him to survive. Even less could they have imagined that this would be a milestone in medical history, leading to the birth of modern neuroscience, according to IFL Science .

The iron rod penetrated Gage's skull from the left cheek through the brain and emerged at the top of the skull, eventually landing a few meters away from the explosion. The accident occurred on September 13, 1984, when Gage used a steel rod to fill the hole with explosives. The iron rod brushed against a rock, creating a spark that ignited the explosives. The impact of the explosion caused the 6 kg, 1 meter long, 3.2 cm diameter iron rod to penetrate his head. Gage was thrown away and lay convulsing on the ground. However, after a few minutes, a miracle happened, he regained consciousness and was able to speak. He then walked and was able to sit upright in his ox cart for the 1.2 km journey back to the hotel.

Dr. Edward H. Williams arrived half an hour after the accident and could not believe what he saw. Gage was sitting on a chair outside the hotel, talking to people around him with an iron bar. It penetrated Gage's skull, penetrated his left lobe of the brain, rupturing part of his brain and pushing his eyeball out of his eye socket. When Williams examined him, Gage stood up too quickly and vomited. However, the next day he was able to walk normally and said he would return to work in two days.

Back in his hotel room, Gage lay down on the bed while Williams and his assistant treated his wounds and bandaged them. He only needed about 10 weeks to recover, much shorter than other similar injuries. During his recovery, he lost his left eye due to swelling and spent several days in a coma due to a fungal infection of the brain. Even so, the team of doctors who treated Gage were amazed at his speed of recovery. Back home, Gage's parents reported that he was even able to work outside the stable and plow the fields. Hospital tests showed that he had no headaches, although his brain activity was clearly visible through the thin skin over the wound.

In 1859, while in Chile, Gage's health began to decline. He began to suffer from epileptic seizures and behave strangely, unlike his previous self. After a short stay with his mother, Phineas Gage died at the age of 36. Although Gage's body was buried, his skull was sent to the Warren Anatomical Museum for analysis.

Although Gage survived, his friends and colleagues noticed major changes in his personality and behavior, according to Dr. John Harlow, who also treated him. In a 1998 article in the journal BMJ, neuroscientists Kieran O'Driscoll and John Paul Leach explored why Gage "wasn't himself" after the accident. They concluded that while the accident didn't cause much physical damage, it did result in major psychological trauma for Gage.

Before the accident, Gage was cautious, hardworking, and well-balanced. Afterward, he became erratic, brash, vulgar, impatient, hesitant, and more instinctive. But Gage's memory and general intelligence were completely unaffected. This led researchers of the time to discover that different parts of the brain were responsible for different aspects of life. Gage's left hemisphere was the only one affected by the accident. So they found that it was the area responsible for controlling personality and impulses.

Researchers also discovered that the brain has the ability to repair itself. Although Gage's new personality traits appeared almost simultaneously with his recovery, over time he began to revert to his old self. Scientists later attributed this in part to social adaptation. Gage's case became the most prominent example of how social cognition and personality depend on the brain's frontal lobe.

An Khang (According to IFL Science )

Source link

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong attends the 80th Anniversary of the Traditional Day of Vietnamese Lawyers](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/09/1760026998213_ndo_br_1-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam visits Kieng Sang Kindergarten and the classroom named after Uncle Ho](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/09/1760023999336_vna-potal-tong-bi-thu-to-lam-tham-truong-mau-giao-kieng-sang-va-lop-hoc-mang-ten-bac-ho-8328675-277-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs a meeting of the Government Standing Committee on overcoming the consequences of natural disasters after storm No. 11](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/09/1759997894015_dsc-0591-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)