|

| There is a legitimate debate about the long-term impact of US liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and whether they are compatible with global climate agreements. (Source: iStock) |

In late January 2024, the US announced that it would suspend applications for liquefied natural gas (LNG) export licenses as it reassesses the economic , environmental and climate impacts of the fuel.

LNG is produced by cooling natural gas into a liquid state, making it easier to store and ship to overseas markets. Natural gas itself is the core ingredient in LNG, and it has been a contentious part of the clean energy debate for decades.

When burned, natural gas emits half as much greenhouse gas as coal. The use of natural gas has helped reduce emissions from the power sector in several countries, including the United States.

However, natural gas is largely made from methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Leaking methane along the supply chain, from production to transportation, threatens to erode the benefits of natural gas as a cleaner-burning fuel.

The immediate reaction to Washington’s decision to ban LNG exports was predictable. Some environmental groups hailed it as a much-needed adjustment, saying it could help the US meet its global climate commitments.

Meanwhile, industry trade groups have attacked Washington’s move, saying it is a counterproductive way to cut greenhouse gas emissions and will undermine the nation’s energy security at a time of increasing geopolitical volatility.

So who's right? Looks like we asked the wrong question!

What matters is not the absolute emissions associated with any cargo ship loaded with LNG departing from the United States, the world’s largest LNG exporter. Rather, when the fuel is exported, the net climate impact depends on what it replaces in the importing country and whether the actual alternatives produce more or less greenhouse gases.

Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine has spurred a surge in US LNG exports to Europe, a fuel used primarily in the power sector for power generation and heating.

If not for the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Europe might still be buying Russian gas. However, evidence shows that Russian natural gas is associated with higher methane emissions than the US natural gas supply chain.

In this context, replacing Russian pipeline gas with US LNG could reduce overall carbon emissions, even with the additional emissions from transporting the fuel across the ocean.

Or to take another example: US LNG exports to India are first used in fertilizer plants or heavy industry, and then in the power sector. This is because solar is the cheapest form of electricity in India. In addition, coal plants generate the majority of electricity, thanks in part to subsidies for the sector.

Given all this, there is no scenario in India, where expensive LNG imports can compete with coal or crowd out lower-carbon renewables. So here too, LNG is almost certainly not going to increase overall emissions from the power sector.

However, this does not mean that US LNG always reduces emissions worldwide. The point of the examples above is that the climate impact of fuels depends on many different factors and must be assessed on a country-by-country basis. Furthermore, whether US LNG reduces net emissions may change over time as countries decarbonize.

There is a legitimate debate going on about the long-term impacts of US LNG exports and whether they are compatible with global climate agreements.

Over the past decade, the way natural gas has helped reduce emissions has been to replace coal-fired power plants. But how long the fuel can continue to help depends on the trajectory of Earth’s emissions and warming.

According to a recent study at the University of Calgary (Canada), LNG exports in general can only reduce global carbon emissions until about 2035, in the scenario where countries achieve the Paris Climate Agreement's goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial times.

That's because by then, there simply won't be enough coal plants in operation to replace them with lower-emission natural gas plants.

|

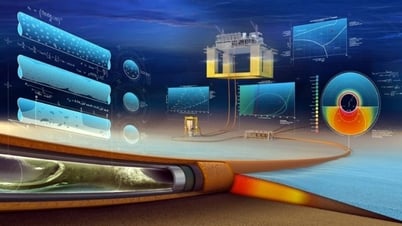

| It would be valuable to consider the climate impact of US LNG exports, especially in the long term. (Source: SMH) |

But if the world misses that temperature target, and most signs suggest it is likely to, natural gas could continue to help cut power sector emissions for a longer period. In a 3°C scenario, natural gas could still replace coal until 2050.

Any climate impact calculations done today need to reflect how US LNG is likely to be used in the future, given changing global demand.

What should America do?

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the Biden administration’s decision to halt exports, one thing is certain: The best thing to do right now to address the climate impact of U.S. LNG is to fix and stop methane leaks along the supply chain as quickly as possible.

In this area, Washington is leading the rest of the world. Federal regulations, government investments and voluntary industry action are poised to reduce methane emissions from the world’s No. 1 economy by more than 80 percent by 2030.

The immediate test, then, is whether other gas-supplying countries can actually be made to meet stricter methane emissions standards. The U.S. Department of Energy is working with several other LNG exporting and importing countries to develop a global framework for monitoring, measuring, reporting and verifying methane leaks.

In a world where LNG consumers like the European Union (EU), Japan and South Korea require suppliers to demonstrate low methane emissions, the United States can lead the world in developing transparent and verifiable low-leakage gas supply chains.

It would be valuable to consider the climate impact of US LNG exports, especially in the long term. Likewise, it would be worthwhile to consider how the fuel could improve global energy security and reduce global carbon emissions.

Each importing country must think carefully about its long-term need for U.S. LNG and develop a sound strategy that balances climate commitments, energy security, and the needs of its people and industries.

Meanwhile, the right question for the US to ask itself is: Are we doing everything we can to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across the entire LNG supply chain, ensuring that it is the cleanest possible energy source for our nations?

The answer starts with doing the hard work to ensure the sector reaches near-zero methane emissions by the end of this decade.

(*) Associate Professor Arvind P. Ravikumar is currently working at the Department of Petroleum Engineering and Geosystems Hildebrand - University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA. He is also a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) based in Washington, USA.

Source

![[Photo] Signing of cooperation between ministries, branches and localities of Vietnam and Senegal](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/24/6147c654b0ae4f2793188e982e272651)

Comment (0)