The alarming rise of "super-productive" scientists

The newsletter of Nature Magazine, a long-standing British science magazine, recently published an article titled The rise in the number of hyper-productive authors worries scientists by author Gemma Conroy (hereinafter referred to as the newsletter of Nature ).

The article discusses the warnings of American and Dutch scientists (through a pre-publication announcement) against the phenomenon of increasing "super-productive" scientists, while Thailand has begun investigating some authors with suspicious publication numbers.

The rise in the number of hyper-productive authors worries scientists published in Nature magazine

At the beginning of the article, the Nature newsletter shares information from a pre-publication study by Dr. John Ioannidis, professor at Stanford University in California (USA) and several other co-authors.

The pre-publication announcement by Prof. Ioannidis's research group is titled Evolving Patterns of Hyper-Productive Publishing Behavior in Science .

According to the definition of Professor Ioanidis's group, extremely productive scientists are those who publish more than 60 articles/year, and the number of extremely productive scientists has increased fourfold compared to less than a decade ago.

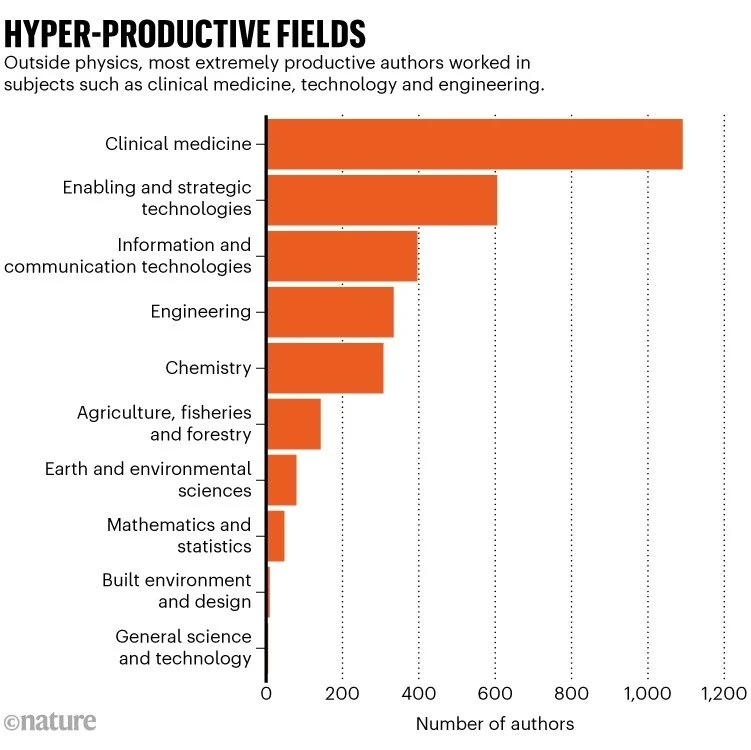

Professor Ioannidis and his colleagues compiled scientific articles, reviews and conference papers indexed in the Scopus database from 2000 to 2022, examining the increase in super-productive scientists by country and by field (except physics, a field in which, due to its specificity, scientists in this field inherently have a large number of publications).

This shows that the field of clinical medicine is home to most of the “hyper-productive” authors (excluding physics), with nearly 700 “hyper-productive” researchers by 2022. Agriculture , fisheries and forestry saw the fastest growth in the number of “hyper-productive” researchers (up 14.6 times between 2016 and 2022). This was followed by biology, mathematics and statistics.

Statistics of fields with many "super-productive" authors from high to low (except physics): clinical medicine, strategic technology, engineering, chemistry, agriculture, forestry and fisheries, environmental and earth sciences, mathematics and statistics, design and built environment, general science and engineering

In 2022 alone, 1,266 scientists (non-physicists) published an average of 5 papers per day (the number of "super-productive" scientists in 2016 was only 387 authors). Professor Ioannidis's group said that surprisingly, the growth rate increased very rapidly starting from 2016 (with signs of increasing since 2014).

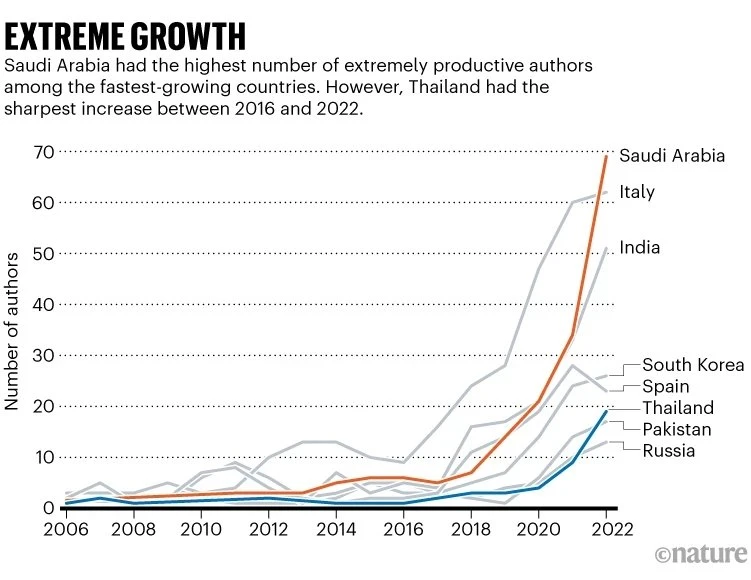

By country, most countries have more than doubled the number of "hyper-productive" authors between 2016 and 2022. Some countries have even made leaps and bounds. For example, Thailand, which had only one "hyper-productive" scientist in 2016, has 19 "hyper-productive" authors in 2022. This is the country with the largest increase in "hyper-productive" authors compared to all countries. But Saudi Arabia is the country with the largest absolute growth, increasing from 6 to 69 "hyper-productive" authors.

Consequences of the policy of counting cards and giving bonuses

The Nature newsletter quoted Professor Tirayut Vilaivan, a member of the Office of Scientific Integrity, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, Thailand, saying that the sudden increase in "super-productive" scientists is a concern for research development standards and policies.

Professor Vilaivan also believes that one of the factors that has led to the country's increase in "super-productive" scientists is Thailand's focus on investing in university rankings, which are based on the number of publications and metrics. Many Thai universities have used monetary incentives to encourage researchers to publish in prestigious journals. If scientists "play" the game right, they can earn up to one million baht (28,000 USD) per year through scientific publications.

Thailand is the country with the highest growth rate of "super-productive" scientists.

Professor Vilaivan added that, according to Nature , the combination of Thailand's growing "publish or perish" culture and monetary rewards is a breeding ground for shady actors. Professor Vilaivan also said that the Covid-19 pandemic was the time when the problem of publishing fake scientific papers began to appear in Thailand.

The Nature newsletter also cited the explanation of Associate Professor David Harding, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand. According to Associate Professor Harding, the increase in the phenomenon of "super-productivity" is contributed by the country's research funding policy, which has shifted to prioritizing large interdisciplinary teams (instead of small groups). Therefore, scientists can easily have their names listed as authors on more scientific papers.

Investigating scientist who published suspicious results

According to Nature , this increase in the number of “super-productive” authors has raised concerns in the scientific community that some scientists are using questionable methods to publish scientific papers. “I suspect that questionable research practices and fraud may be behind some of the most extreme behavior,” said Professor Ioannidis, co-author of the aforementioned pre-publication. “Our data provide a starting point for discussions about these issues across the scientific community.”

Sharing with the author of the Nature newsletter, Professor Ioannidis said that to prevent the rising wave of "hyper-productive" scientists, research organizations and funding agencies should focus on the quality of scientists' work rather than the number of papers they publish. This will prevent scientists from taking shortcuts.

But according to Nature , Thai authorities have noticed something unusual about the sudden surge in scientific productivity, and have begun investigating scientists with suspiciously high numbers of publications. Earlier this year, the Thai Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation investigated whether misconduct had occurred at Thai universities by examining scientists with unusually high publication records, or some of their papers were outside their area of expertise. The investigation found that 33 scientists at eight universities had paid to be credited on papers, and dozens more were suspected of having their names on papers they had purchased.

Source link

![[Video] Groundbreaking ceremony of inter-level boarding schools in the border areas of Tuyen Quang and Lao Cai](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/09/1762702287645_lao-cai-ha-giang-6159-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)