Raising a child in South Korea is no easy task. As soon as their child is a toddler, many parents are frantically searching for elite private preschools.

By the time these toddlers turn 18 and become teenagers, they will face the stressful eight-hour national college entrance exam to win a ticket to a prestigious university.

But getting past this milestone is a difficult, costly and stressful journey for both parents and children. Many researchers, policymakers, teachers and parents blame the country’s repressive education system for a host of problems, from educational inequality to youth mental illness and even the country’s plummeting birth rate.

Hoping to address these problems, the South Korean government has taken a controversial step: simplifying the college entrance exam.

South Korean students take the national college entrance exam at a school in Seoul on November 17, 2022. (Photo: Getty)

Speaking at a press conference on June 26, South Korean Education Minister Lee Ju-ho said that all difficult questions in the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) will be eliminated.

Mr Lee said the classic series of difficult questions sometimes included knowledge that was not covered in the public school curriculum, giving students who took private tutoring classes an advantage. He added that although tutoring was a personal choice, many felt it was a necessity due to the pressure of fierce competition to score high on exams.

“We are looking to break the vicious cycle of private education increasing the burden on parents and eroding the fairness of education,” Mr. Lee said.

Tricky questions and life-changing exams

By the time Korean teenagers enter high school, much of their lives revolve around studying and preparing for the CSAT - a pivotal moment that determines a student's future.

The reason why Korean students are so afraid of this exam is because of the classic set of difficult questions that have been on the exam for many years. These “deadly” questions range from advanced calculations to extremely difficult literary excerpts.

Faced with the pressure of achieving high scores in tough exams, most Korean students choose to take private tutoring or study at private cram schools (hagwons), which makes their study schedules packed.

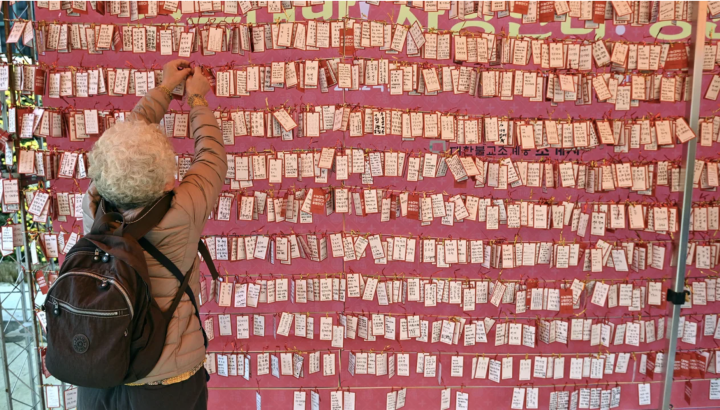

A student's grandmother hangs a name tag for her grandson at a temple in Seoul, praying for his success in the university entrance exam. (Photo: Getty)

According to CNN , most Korean students go to school during the day to attend regular classes. After school, they quickly go to cram schools to study in the evening. Then they return home and continue to study by themselves until early morning.

As a result, the private exam preparation industry in South Korea has grown enormously and is hugely profitable. According to the Ministry of Education, in 2022, South Koreans spent a total of 26 trillion won (nearly $20 billion) on private education. That’s nearly as much as the combined GDP of countries like Haiti ($21 billion) and Iceland ($25 billion).

Minister Lee said that in 2022, students in elementary, middle and high schools spent an average of 410,000 won ($311) a month on private education - the highest figure since the education ministry began tracking the data in 2007.

This is also why many Korean parents of all income levels pour all their resources into their children's education, fearing that their children will fall behind. The burden is significantly higher for poor families, who have to spend a larger portion of their income on their children's education than more affluent households.

The education race with huge costs

This educational race is taking a heavy toll on both students and parents. Critics have long argued that the pressure on students to perform is a factor in the mental health crisis in South Korea – which has the highest suicide rate among OECD countries.

Last year, the South Korean health ministry warned that suicide rates were rising sharply among teenagers and young adults in their 20s. A 2022 government survey also found that among nearly 60,000 middle and high school students nationwide, nearly a quarter of boys and a third of girls admitted to having suffered from depression.

Most South Koreans believe that “giving up or delaying having children is a way to avoid poverty.” (Photo: Getty)

Education also puts heavy pressure on parents. Experts believe that the huge expenditure on children's education is one of the main reasons why Koreans are increasingly reluctant to have children.

South Korea consistently ranks as the most expensive country in the world to raise children from birth to 18, largely due to the cost of education. Many couples feel they can only focus their resources on one child.

In 2022, South Korea's fertility rate fell to a record low of 0.78 – 50% lower than the standard (2.1) to maintain a stable population density, and much lower than Japan (1.3) – the country with the world's oldest population.

“The high cost of raising children takes up a large portion of the budgets of low-income families. Without additional income, having children leads to lower living standards and puts low-income families at risk of poverty,” the OECD report said in 2018, adding that “forgoing or delaying having children is a way to avoid poverty.”

A step in the right direction?

Efforts to address the problem have so far been largely ineffective. The South Korean government has spent more than $200 billion over the past 16 years to encourage people to have more children, but with little success.

Activists say South Korea needs deeper changes instead, such as dismantling entrenched gender norms and providing more support for working parents.

Regarding the goal of simplifying the CSAT exam, many organizations and people welcomed this decision, saying that it is necessary to free students from excessive competition.

On June 26, the education minister criticized private education centers for profiting from the anxiety of parents and students, while pledging to make the system fair and “eradicate” the culture of extra tutoring.

To this end, the government has set up a hotline for citizens to report misconduct by these establishments. The government will also provide more after-school tutoring programs in the public sector, and provide better childcare services to prevent students from being forced to attend cram schools, the minister said.

The South Korean Ministry of Education last week released a number of mock tests, which compile questions drawn from previous CSAT tests to assess the percentage of students who can solve difficult questions, thereby eliminating tricky questions from future tests.

Phuong Thao (Source: CNN)

Useful

Emotion

Creative

Unique

Wrath

Source

Comment (0)