Established in 1975, shortly after the country's reunification, the War Remnants Museum (No. 28, Vo Van Tan Street, Ward 6, District 3, Ho Chi Minh City) is a place that preserves authentic and vivid evidence of war crimes, especially during the period of resistance against the US to save the country.

With an area of about 4,500 square meters, the Museum consists of a main three-story building and an outdoor exhibition area, where war vehicles such as tanks, airplanes, bombs, and a model of a “tiger cage” – a place to detain and torture prisoners in Con Dao. The exhibition content at the Museum is not chronological but is presented mainly in order of issues; orienting the exhibition content towards the community and for the community; building a story in the exhibition connecting the past to the future; organizing forms of exchange related to the exhibition content.

Through many revisions and upgrades, the Museum has built a diverse and in-depth display system with prominent topics such as: "Historical truths", "Memories - Photo collection about the US invasion war in Vietnam", "Vietnam - War and peace ", "War crimes of invasion", "Consequences of Agent Orange/dioxin in the invasion war in Vietnam", "Prison regime in the invasion war in Vietnam", "The world supports Vietnam's resistance", "Weapon artifacts displayed outdoors", Experience room for children: "White Dove"...

War Remnants Museum

I arrived at the War Remnants Museum on a bright sunny day. With each slow step stopping in front of the Museum gate, I couldn’t help but feel my heart beating faster. Quietly lining up with many domestic and foreign tourists waiting for their turn to enter the exhibition room, I didn’t bring much with me, just an open heart and a heart ready to listen to history tell its story through its wounds.

Right from the first exhibition rooms, I felt a melancholy covering the space. Black and white photos, documentary films, simple but haunting lines, bit by bit, hit my senses like a silent scream from the past. I trembled. Not only because of the cold from the air conditioning in the room, but because of a deep shock in my heart: I - a person born in peacetime - had never imagined that war could be so present, so haunting, and so painful!

A corner of the war weapons display room

I walked into the weapons showroom, a cold room with brightly lit glass cabinets – inside were countless types of guns and ammunition, from rifles, submachine guns, to heavy machine guns. The variety and ferocity of that arsenal took my breath away. Not because I admired the technology, but because I was horrified by the scale of the brutal war that America had unleashed on this small land. Behind each gun were blood, tears, and thousands of human lives.

A series of images of massacres, mutilated bodies, naked children running away from bombs and bullets… all made me choke. I didn’t dare to breathe heavily. I was afraid that if I wasn’t careful, every step I took would accidentally step on the memories of the dead – those who had suffered the ultimate pain at the hands of the invaders. I felt like I was lost in the middle of a blood-stained time stream, swept away by every painful glance in the photo, every name engraved on the memorial, every piece of torn cloth still stained with time.

When I entered the exhibition area about the consequences of Agent Orange, I could no longer keep my composure. The photos of the victims, with their deformed figures, lifeless eyes, and deformed bodies due to the poison, really broke me down. I could not hold back my tears. I felt my heart shrink. There was something both indignant, sorrowful, and helpless rising up inside me. How could people be so cruel as to spread such poison on so many lands, bodies, and the future of a nation?

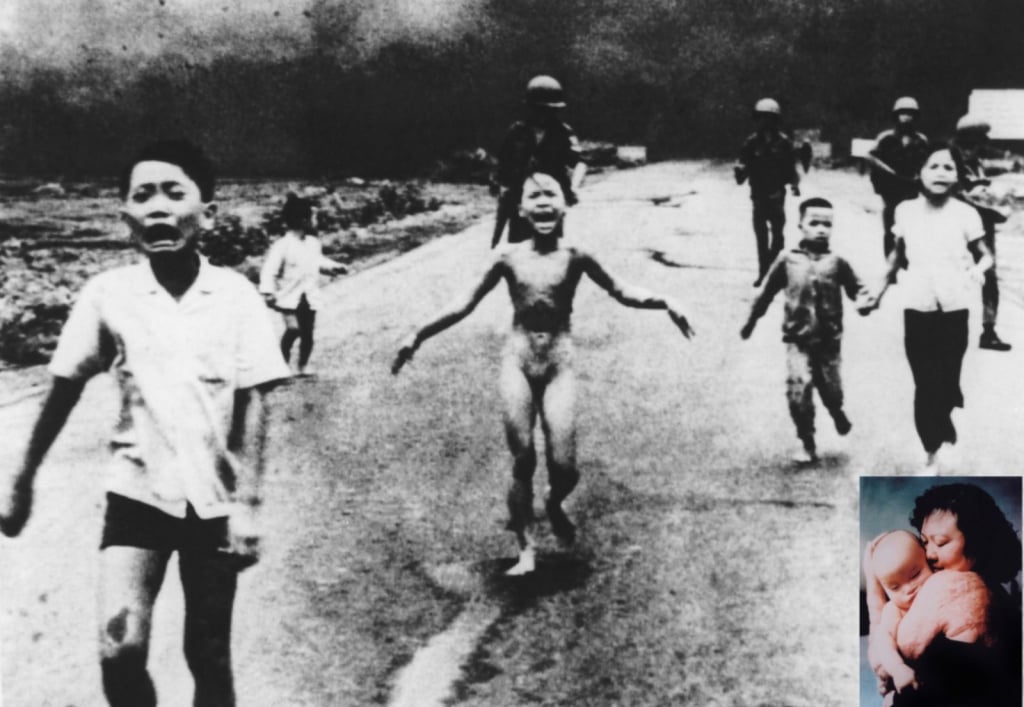

Little girl Phan Thi Kim Phuc was burned by an American Napalm bomb (Trang Bang, Tay Ninh in 1972).

Among the artifacts and images in the exhibition, there was a photo that made me unable to contain my emotions, it was the famous photo of a naked girl, her whole body burned, running in panic on the road after a napalm attack in Trang Bang, Tay Ninh. Around her were other children in panic, behind were Saigon puppet soldiers with guns in their hands.

I stood still in front of that photo for a long time. The first feeling was shock. The photo was black and white, obscured by smoke and fire, but nothing could obscure the naked pain of the children in it. The little girl in the photo – a symbol of the pain of war – seemed to want to scream out her despair on behalf of millions of Vietnamese people who had suffered the disaster of war. I felt myself trembling, my heart aching, partly out of pity, partly out of indignation at the inhumane cruelty that war had sown.

Right next to it are photos of the consequences of Agent Orange – deformed bodies, sad, nameless eyes. Among them is a photo of a mother holding her deformed child in her arms – that maternal love is both beautiful and heartbreaking. But along with that feeling of extreme sadness, in each photo displayed here there is still a belief in justice – a belief that I see in many people in the stories told in this Museum: mothers demanding justice for their children, fathers knocking on the doors of international organizations to fight, victims who have overcome pain to live on and tell their stories. They did not give up, and that makes me admire them more than ever.

Ca Mau mangrove forests were destroyed by toxic chemicals during the Vietnam War.

War not only destroys homes and fields, but also destroys childhoods, casting darkness over innocent lives. I felt that deeply and profoundly when I saw the images displayed at the Museum. They are not simply evidence, but slices of the nation's body, still scarred after many years of peace. And in that space, I felt like I became a part of history - a late witness, but full of emotion and awareness. I admire those who courageously sought justice for the victims, and I admire the tenacious vitality of those who overcame pain to continue living and hoping.

I hate, I am angry. Angry at the hands that sowed war, angry at those who used the name of freedom to trample on the freedom of others. But in the midst of that anger, I realized that my heart was filled with more than just hatred. I know that the greatest thing this place is whispering to me is not to harbor hatred, but to remember. Remember so as not to repeat it. Remember so as to live a worthy life. Remember so as to cherish the peace we have.

Leaving the Museum, my whole body enveloped by the bright sunlight of those historic April days, I felt as if I had just experienced a heavy rain inside. My soul was drenched by loss, but also sparkling with light from stories of overcoming adversity. I suddenly understood that being born in a time of peace was not to be indifferent to the past, but to preserve what our predecessors had exchanged with their blood, tears and souls.

I bowed my head, silently promising myself: to live more kindly, more gratefully, and more patriotically, in the most practical way a young person can, which is to remember, retell, and spread the lessons that the Museum today has sent to my heart.

Thanh Mai

Source: https://baohungyen.vn/bao-tang-chung-tich-chien-tranh-noi-luu-giu-ky-uc-bi-thuong-ma-kieu-hanh-3180764.html

Comment (0)