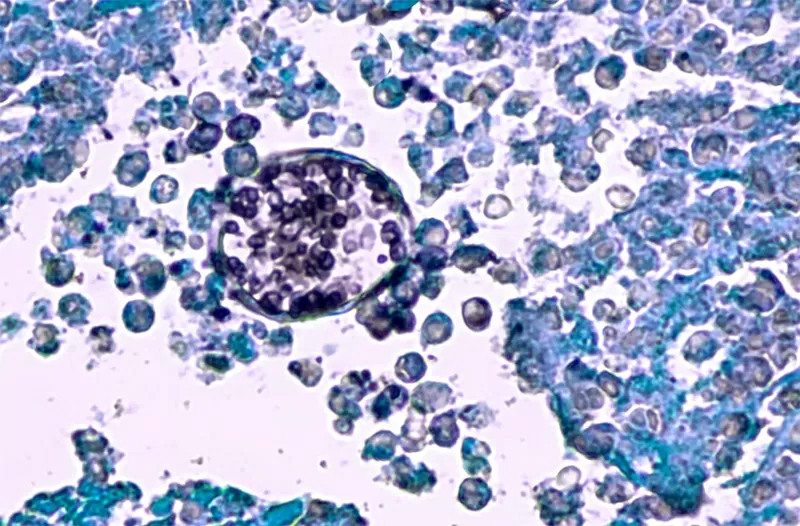

Mucormycosis, which often results in the loss of an eye, is difficult to treat. Photo: Shutterstock |

When most of us think of dangerous infections, we picture bacteria or viruses. But for infectious disease experts like Peter Chin-Hong, one of the most dangerous threats lurking in hospitals and clinics today is fungus.

Chin-Hong’s case list is long: a 29-year-old marathon runner from California’s Valley City whose heart lining was invaded by coccidia, a fungus that lives in soil; a lung transplant recipient who coughed up nodules of mold—fungal growths scattered throughout her lungs—after stopping antifungal medication; and a 45-year-old woman with poorly controlled diabetes who contracted a black fungus that destroyed part of her face and spread to her brain, and died despite multiple surgeries and treatments.

“These cases are no longer rare,” said Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “We see them every day.”

An estimated 6.5 million people develop invasive fungal infections each year, of which approximately 2.5 million die directly from the disease – twice the number of deaths from tuberculosis globally. |

Once considered obscure or opportunistic, invasive fungal infections are now appearing with alarming frequency—in patients and places where doctors have never worried.

Climate change is expanding the geographic range of fungi. Medical advances such as organ transplants, chemotherapy and intensive care are saving lives, but they are also leaving many immunocompromised patients vulnerable.

Even common medical conditions like diabetes increase your risk of developing a serious fungal infection.

This skin fungus is very difficult to treat, has a high risk of death, and treatment methods are limited. |

An estimated 6.5 million people develop invasive fungal infections each year, with approximately 2.5 million deaths directly attributable to the disease – twice the number of deaths from tuberculosis globally.

Many of these deaths occur in people with late-stage HIV and experts warn the problem could get worse as funding for global HIV/AIDS programmes is cut.

The rise in AIDS-related illnesses could exacerbate the fungal crisis, especially in low-resource settings where diagnostic tools and antifungal treatments are already limited, they said.

Adding to the danger is the rise of drug-resistant infections—strains that no longer respond to the limited arsenal of antifungal drugs. Candida auris, a new yeast that first emerged in 2009, has caused deadly outbreaks in hospitals and long-term care facilities.

Experts warn that wider resistance could soon outpace the slow pace of new drug development.

Fungus is not on anyone's radar. It is unobserved and uncontrollable – which means we don't develop mitigation measures. Justin Beardsley, infectious diseases physician and researcher at the University of Sydney |

Mushroom crisis

The World Health Organization warns of serious global gaps in the ability to diagnose and treat fungal infections, including a dangerously thin drug pipeline, with just four new antifungal drugs approved globally in the past decade.

Of the nine drugs currently in clinical development, only three have reached the final stages of patient studies.

“We can expect few new approvals in the next 10 years,” said Valeria Gigante, head of the antimicrobial resistance unit at the WHO in Geneva.

More than half of the antifungal drug candidates under development lack real innovation, limiting their ability to combat emerging resistance, Gigante added.

Justin Beardsley, an infectious diseases physician and researcher at the University of Sydney who contributed to both WHO reports, said the fungal threat remains dangerously overlooked.

“The fungus is not on anyone’s radar,” he said. “It is unobserved and uncontrollable – which means we don’t develop mitigation measures.”

He also pointed to growing concerns about the use of antifungal drugs in agriculture .

Many of the new drugs being developed do not have novel mechanisms of action, says Beardsley. In many cases, new compounds are being introduced into agriculture more quickly to protect crops from diseases like powdery mildew.

“That really frustrates drug developers for humans and raises some public health concerns that our new hopeful drugs will be exposed to the same biological agent in the environment and we will get resistance.”

Another shortcoming concerns diagnosis, with the WHO warning that even when tests exist to identify the deadly fungus, they are often not available in low- and middle-income countries.

Most rely on well-equipped laboratories and trained staff. Gigante said the development of systems to detect invasive fungal infections and determine drug susceptibility also lags behind what is available for bacteria.

Coccidioides fungus seen under a microscope. This fungus causes coccidioidomycosis, also known as valley fever, which is common in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Photo: Shutterstock |

Invisible Enemy

Fungal infections behave differently than bacterial and viral infections. They rarely spread from person to person, but instead most come from the environment—moldy soil, rotting plants, airborne spores. Some spores can even float high into the atmosphere and drift across continents, making them particularly difficult to track or control.

That makes it nearly impossible to fully protect vulnerable patients. Doctors often prescribe preventative antifungals for people at high risk, such as those who have had lung or blood stem cell transplants, but these drugs don’t cover every type of mold, says Chin-Hong.

The professor also added that mucormycosis – a rare but very dangerous fungal infection – is known to be very difficult to treat. If mucormycosis invades the lungs, the mortality rate can be as high as 87%.”

The fungus can also invade the sinuses and spread to the brain, where it has a fatality rate of about 50%. It causes tissue death - cutting off blood flow so antifungal drugs cannot reach the site of infection.

“You have to surgically remove the infected area,” he said. “A lot of times people have to have their eye taken out because it goes up through the sinus cavity, and there’s no good treatment for that.”

Excision – surgical removal of infected tissue – is sometimes possible in the sinuses or skin. But in the lungs, it is often much more difficult.

The reason lung cancer mortality is so high, says Professor Chin-Hong, is that it is not possible to remove only large lung masses. Even when drugs work, they are often less effective in patients who need them most – those with weakened immune systems.

Source: https://baoquocte.vn/chu-y-benh-nam-da-nay-kho-chua-nguy-co-tu-vong-cao-phuong-phap-dieu-tri-con-han-che-310932.html

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman attends the seminar "Building and operating an international financial center and recommendations for Vietnam"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/28/76393436936e457db31ec84433289f72)

Comment (0)