The US political establishment is working to finalize a plan to raise the debt ceiling, but even if successful, it will not eliminate the risks for the country or the world .

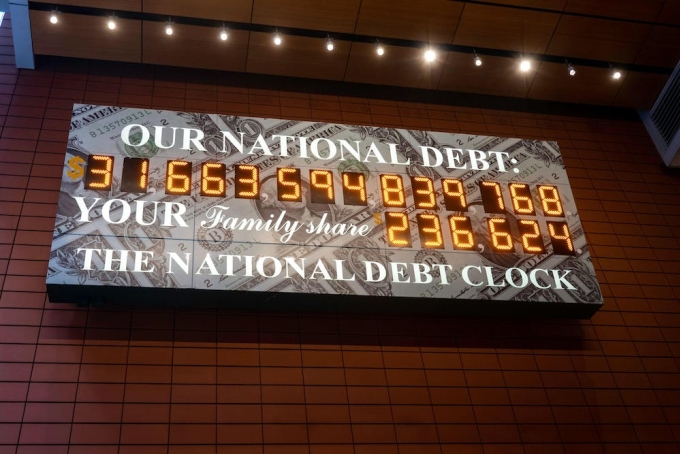

On a wall in Manhattan, not far from Times Square (New York), the U.S. national debt clock has risen from $3 trillion (when it was inaugurated in 1989) to over $31 trillion. After years of continuous increases without any apparent recession, and having been moved from a busy street corner to a quieter alley, the clock has largely gone unnoticed.

But now, the relentless escalation of public debt, as reflected by the clock, is becoming a major concern. The figures are now soaring above the US debt ceiling, and that poses a risk not only to the country but to the global economy .

The debt ceiling is the maximum amount of money Congress allows the U.S. government to borrow to meet basic needs, from paying for health insurance to military salaries. The current total debt ceiling is $31.4 trillion, equivalent to 117% of U.S. GDP. On May 1st, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that the government would run out of cash reserves and funding options as early as June 1st.

At that point, the US would face either a national debt default or drastic cuts in government spending. Either outcome would also devastate global markets, according to The Economist .

Because a default would erode confidence in the world's most important financial system. Meanwhile, choosing large-scale budget cuts could trigger a deep recession for the world's largest economy.

Even if Congress manages to raise the debt ceiling before anything serious happens, the move would still be a wake-up call about the deteriorating and difficult-to-recover financial health of the United States.

The US debt clock in Manhattan, New York, in November 2022. Photo: Patti McConville

The Economist stated that the debt ceiling is a political invention of the US with no fundamental economic meaning, and no other country would tie its own hands so brutally. And because it is a "political invention," it also needs a "political solution."

Investors began to worry, unsure whether Democrats and Republicans could work together to resolve the issue. Treasury yields maturing in early June rose one percentage point following Yellen's warning, a sign that fewer people wanted to hold U.S. government bonds.

A bill proposed by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy would raise the debt ceiling by 2024, while cutting trillions of dollars in spending over the next decade and abandoning climate change plans. The bill was passed by the Republican-controlled House on April 27th, but because it was not initiated by Democrats, it will not pass the Senate.

However, it is being bet that American politicians will somehow find a way to break the deadlock, as they have done in the past. President Joe Biden has invited leaders from both parties to the White House on May 9th. There, they will negotiate to create a mutually satisfactory debt ceiling bill.

If and when this happens, the public debt clock will no longer sound the alarm. But the fact remains unchanged: America's finances are increasingly precarious. In other words, the core measure of fiscal vulnerability is not how much the U.S. owes, but how large its budget deficit is.

Over the past half-century, the U.S. federal budget deficit has averaged around 3.5% of GDP per year. Some politicians consider this level evidence of wasteful spending. Meanwhile, in its latest update in February, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected the deficit would average 6.1% over the next decade.

According to The Economist , this is still a conservative forecast because the CBO is not taking recessions into account, but rather normal economic conditions. Even without the massive spending seen during Covid, a recession would still lead to a larger deficit as tax revenues fall while social security spending, such as unemployment insurance, increases.

Additionally, the CBO initially estimated that spending on subsidies for things like electric vehicles and renewable energy under the Biden administration would cost around $400 billion over the next decade. But because so much of the subsidy went in the form of unlimited tax credits, Goldman Sachs now estimates the actual amount needed would be $1.2 trillion.

Furthermore, the CBO only makes predictions based on current law. As the political landscape changes, so do the laws. In 2017, Donald Trump implemented massive tax cuts, which are set to expire in 2025. When making predictions, the CBO should have assumed they would end as planned. However, very few politicians want to raise taxes. Biden is also seeking to forgive student debt, which would further increase the deficit.

In short, considering only the fundamental variables, including higher spending on industrial policy and continued tax cuts, the average budget deficit will be 7% over the next decade, and nearly 8% by the early 2030s, according to The Economist .

Year after year, increasing borrowing will only fuel the mountain of national debt. The CBO forecasts that federal debt will double, reaching nearly 250% of GDP by the middle of the century. Before that time, New York's debt clock, currently running at 14 digits, will need a 15th digit as public debt surpasses $100 trillion.

There are no clear thresholds for public debt or deficits that, if exceeded, would immediately become a serious problem. Instead, widening these two indicators has an "eroding" effect on the economy. As the mountain of debt grows higher, coupled with rising interest rates, debt repayment becomes even more difficult.

At the beginning of 2022, the CBO projected an average interest rate for 3-month US loans of 2% for the next three years, but has now revised it to 3.3%. Interest rates could fall in the future or remain high for an extended period. In the current high-interest-rate environment, large deficits could create problems.

To raise funds through borrowing, the government must attract a larger portion of private sector savings. This leaves less capital available for business spending, reducing investment capacity. With less new capital injected, income growth and people's productivity slow down. The result will be an economy that is both poorer and more volatile than when budget deficits are controlled.

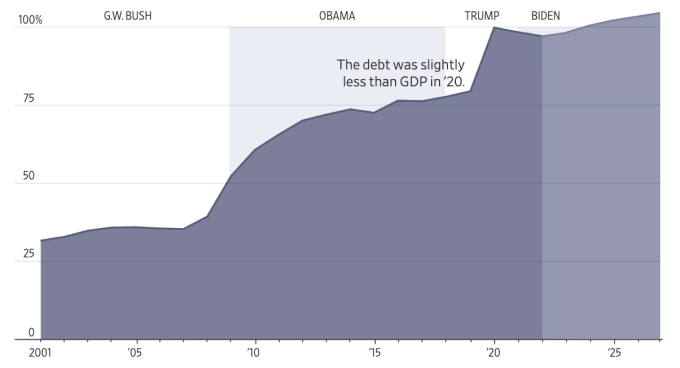

The ratio of US public debt to GDP (%) across different presidencies. Graphic: WSJ

The White House estimates that funding for social security and healthcare programs will collapse in the early 2030s. At that point, the U.S. will face a fundamental choice between cutting benefits and raising taxes. The same will apply to all other financial aspects of the federal budget.

"The average American has lived through the 21st century with presidents saying we have no problems. So why should people bother with difficult reforms now?" said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who headed the CBO under George W. Bush. He predicted a generation of voters who wouldn't be able to get anything they wanted, because the money had already been spent in the past.

Doug Elmendorf, who headed the CBO under Barack Obama, said Republicans have learned that cutting benefits is toxic, while Democrats know they must avoid raising taxes. Both approaches are very costly for the federal budget. "So it's increasingly difficult for each side to develop a sustainable fiscal policy plan, let alone agree on a set of policies," he said.

Phiên An ( according to The Economist )

Source link

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 3] Ultra-thin rice paper takes off.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F28%2F1769562783429_004-194121_651-081010.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)