While looking to buy plants to decorate his coffee shop, Tran Bao Huy saw people picking bunny ear cactus to stir-fry with meat, and the idea of starting a business popped into his head.

The man born in 1989 immediately called his wife and said: "Close the coffee shop, I have found a new way to start a business."

It was 2021, Tran Bao Huy had just quit his job managing a homestay in Da Lat to return to Khanh Hoa to open a coffee shop. Hearing from friends that the bunny ear cactus was a beautiful decorative plant, he went to buy it.

"The seller pointed to a cactus growing on the fence in front of the door and asked if this was the right variety, then conveniently picked one to cook for dinner," Huy said.

He did not expect this thorny plant to be edible and was even more excited when he was introduced to its other uses such as treating bone and joint problems and diabetes.

While working as a mechanical engineer for a Japanese company in Ho Chi Minh City and later as a homestay owner in Da Lat, Huy had always wanted to start a business in agriculture. Having traveled along Central Vietnam and witnessed many areas being desertified where no plants could survive, Huy thought that prickly pear cactus would be the savior of these lands. Further research revealed that this plant had been experimentally grown in Ninh Thuan as animal feed, but the project failed due to a lack of market demand.

"If fresh ingredients can't compete, then process them into food," Huy told his wife. After watching videos of people in Mexico processing cactus into juice, pickles, cakes... he decided to try it.

Huy ordered 3,000 trees from Phu Yen and temporarily planted them on his parents' land. Seeing her son, who used to work for a foreign company and earned thousands of dollars, quit his job to find a way to grow cacti - a plant that was only used for hedges, Mrs. Tran Thi Que was "worrying", afraid that her youngest son was going crazy.

Huy and his wife went to Da Lat to rent 3,000 square meters of land to grow cacti, preparing ingredients to make some dishes such as pickling and making juice. "But the pickled cacti had a white scum and were slimy, while the juice tasted undrinkable," Huy recalled of the first experimental batch.

He knew he needed to learn about food technology, so he bought books to research and watched foreign videos on how to process cactus. But after a year of experimenting, Huy's product was just failure after failure.

Meanwhile, the cactus garden in Da Lat was slowly dying because snails were devouring it. Huy tried every method to prevent it, from spreading lime powder to scattering eggshells, but after a few days of heavy rain, all his efforts were washed away.

Seeing thousands of cacti withering away, the couple left Da Lat and moved to Ninh Thuan to build a new garden.

The land they chose was Bac Ai, a mountainous district in Ninh Thuan province with a semi-desert climate and arid land, suitable for growing cacti. They rented a 3-hectare plot of land and planted 5,000 new plants. Four months later, the cacti gave their first harvest.

Huy used fresh ingredients to continue his research on making pickled vegetables with fruit juice. After three months, the pickled vegetable product was successful. At this point, he wanted to open a small production workshop with a closed-loop and modern process.

But in a land with more than 95% Raglai and Cham ethnic people, after searching for a month without being able to rent a suitable workshop, Ms. Minh became discouraged and advised her husband to give up and return to the city.

"Give me two more years, and if I don't succeed, I'll listen to you," Huy promised his wife, then wrote a commitment letter himself.

A few weeks later, they found a newly built house, more than a kilometer from the garden, to use as a workshop. Huy bought additional processing machines, presses, material cutters, and sterilizers to process pickled cactus and then sell them experimentally on his personal page.

The product had just become familiar with the market when Huy wanted to expand the factory, the owner asked for the house back. The garden owner also wanted to take back the land. The couple's nearly year's worth of effort was once again wasted.

The young couple gritted their teeth and painstakingly dug up thousands of cactus plants to transport back to their hometown in Phu Yen. "Cactus thorns pricked our hands, faces, and all over our bodies, but no one dared complain, for fear of an emotional outburst," Huy recalled.

After a week of cleaning the garden, the couple was tanned from sun exposure. There were days when they couldn’t even swallow the rice because they couldn’t breathe. Luckily for them, the climate suited their plants, so they grew well, and had enough raw materials to continue researching how to make juice.

In July 2023, the first bottles of cactus juice were successfully produced, and they could be preserved for a year in the natural environment.

"I was so happy I cried," Huy recalled. "It took more than two years of sweat, tears and blood to get the finished product."

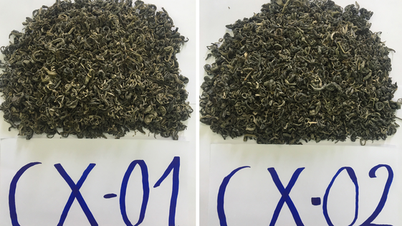

Having achieved success with cactus juice and pickled vegetables, this man continued his research to develop tea bags and starch to aid in the treatment of diabetes.

In early 2024, after receiving the food safety certificate, Huy set up a factory and launched the product on the market. He purchased raw materials from several coastal provinces and called on 20 more households in Phu Yen to grow bunny ear cactus to supply the company.

In mid-2024, Huy's products made from bunny ear cactus entered the final round of the 10th Green Startup - Sustainable Development competition nationwide.

Along with the promotion of word of mouth, the juice, tea bags and cactus powder are becoming more popular in big cities like Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi.

Witnessing Huy's entrepreneurial journey, Mr. Nguyen Xuan Duy, lecturer of the Faculty of Food Technology at Nha Trang University, Head of the Phu Yen Province Startup Club, commented that this man has a determination and perseverance that few people have.

"Huy is the first person to develop food from prickly pear cactus not only in Phu Yen but nationwide," Duy said, believing that Huy's project has great potential to develop into a commercial production and business model in arid areas where it is difficult to grow other crops.

Now that she sees her son appearing in the media, promoting products made from prickly pear cactus, Mrs. Que no longer asks when her youngest son will go to the city to work.

Every time Huy called to ask, his mother laughed: "He looks crazy but he still makes things happen."

Source

![[Video] The craft of making Dong Ho folk paintings has been inscribed by UNESCO on the List of Crafts in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/10/1765350246533_tranh-dong-ho-734-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)