From thousands of Vietnamese students diligently studying abroad to young PhDs packing their bags and returning home, the question "Stay or return home?" has never been easy to answer.

Many major problems have been raised:

- How can we "nurture" Vietnamese scientists who are capable of "swimming" in the global market?

- Once talented individuals have been trained and honed in an international environment, how can we attract them back home?

- And once they return, what is the solution to the problem of retaining talent, so that they not only stay but also fully realize their potential?

We listened to the stories of young scientists who chose to return to serve their homeland, to gain some insight into the bottlenecks and obstacles they face.

No matter where they are, Vietnamese people always yearn for their homeland. But if they had clear plans and a roadmap, the answer to the question "what will we do for our country today?" would become much clearer to them.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Education and Training , there are currently nearly 250,000 Vietnamese students studying abroad at the high school, university, and postgraduate levels.

This includes nearly 4,000 students studying abroad on state-funded scholarships managed by the Ministry of Education and Training , accounting for approximately 1.6% of the total number of Vietnamese students studying overseas.

Students who study and conduct research abroad using non-state budget funds mainly receive scholarships and are self-funded.

With these choices, the journey of investing in knowledge goes beyond just academic effort; it's also linked to a long-term financial strategy.

The pressure and expectations stemming from that investment can become the deciding factor in whether someone stays or returns after graduation.

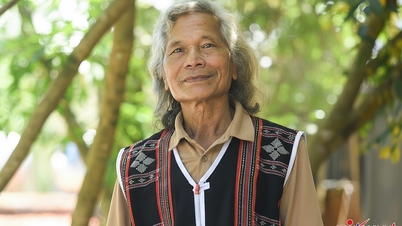

Dr. Pham Thanh Tung is a lecturer at VinUni University. After graduating from Hanoi Medical University, he received a full scholarship from the Vietnam Education Foundation (VEF) to pursue a master's degree at Johns Hopkins and a doctoral scholarship from Harvard University.

Dr. Tung noted that one of the major challenges today is the decrease in international aid for scholarship agreements and Vietnamese government scholarships compared to the past.

This is partly due to Vietnam's entry into the middle-income group, which leads international organizations to prioritize allocating resources to more disadvantaged countries.

"As state-funded scholarships become scarce, many young people have to seek scholarships from universities or cover their own tuition costs."

For self-funded students, financial pressure becomes a crucial factor in the decision to stay or return after graduation, especially when they need time to work abroad to recoup the investment in their degree,” the young PhD holder said.

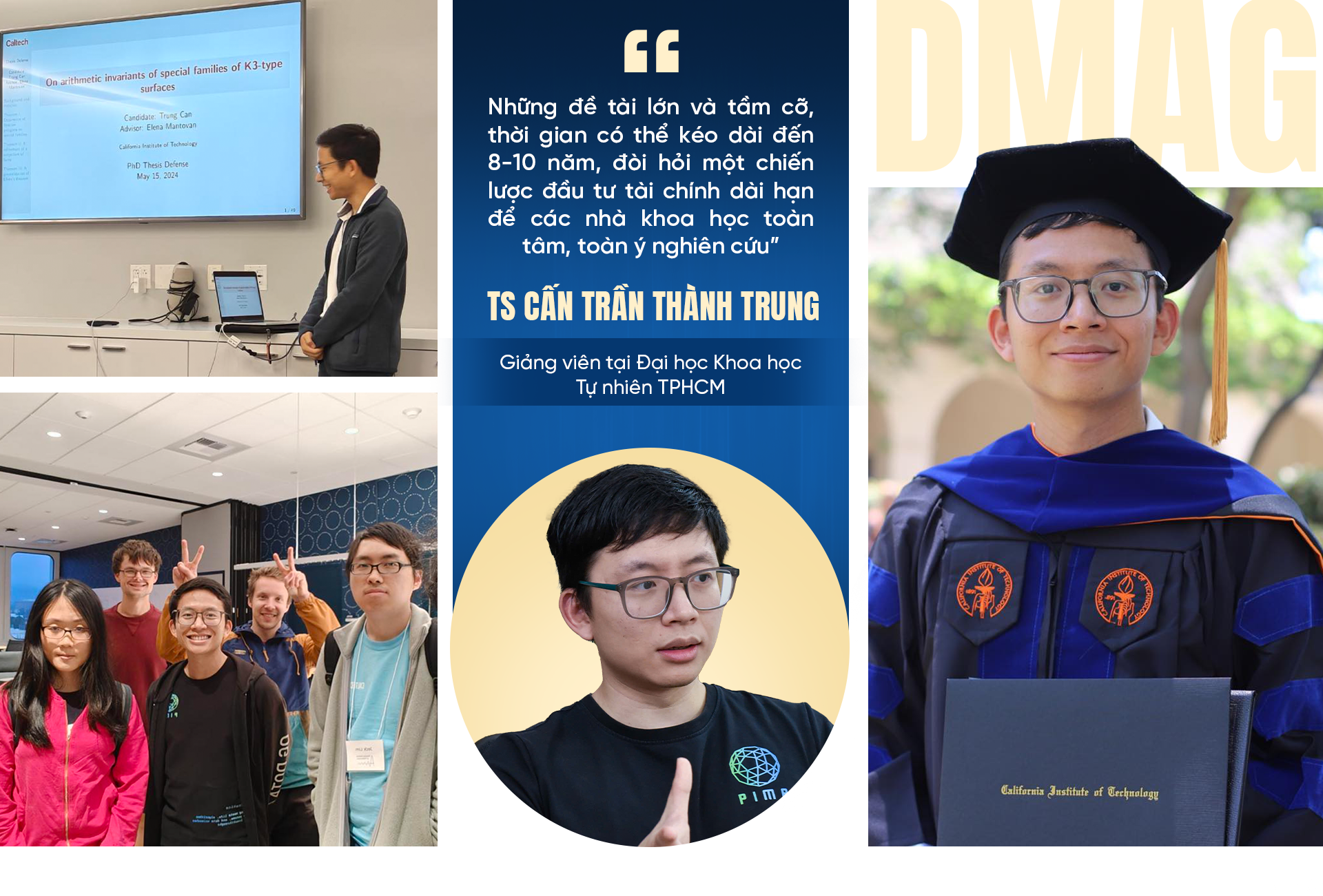

Dr. Can Thanh Trung, a young man born in the 1990s who returned from the California Institute of Technology and is currently teaching at the University of Science and Technology in Ho Chi Minh City, shared:

"In many cases, studying abroad is considered a major investment for the family, leading to pressure to quickly achieve an income level to offset the expenses."

According to the young PhD holder, those who receive full scholarships are generally less constrained financially, while those who self-fund must prioritize high-paying career opportunities, which may lead them to carefully consider whether to stay abroad or return home.

Dr. Thai Mai Thanh is currently a lecturer in the Mechanical Engineering Program at the Institute of Engineering and Computer Science, VinUni University. After completing his PhD in Biomedical Engineering at the University of New South Wales (Australia, 2023), the young man decided to pack his bags and return home.

Dr. Thanh believes that self-funded overseas study is a significant investment, and gaining admission to top universities worldwide is a considerable challenge.

However, the impact of these individuals upon their return depends on the working environment and conditions in their home country.

According to him, state-sponsored scholarship programs can create clearer commitments and guidance, helping those who return to make a lasting impact.

From Dr. Thanh's perspective, many students are doing research in Vietnam but then stop and don't continue. "The allure of an international environment remains very strong," Dr. Thanh explained.

"Convincing PhD students in Vietnam to pursue doctoral studies is extremely difficult, because many of the students I'm supervising could easily obtain PhD scholarships abroad," Dr. Thanh shared.

According to Dr. Thanh, to truly attract them, it is necessary to provide a laboratory with complete infrastructure, implement new research topics and sufficiently large problems, and also offer other benefits such as health insurance.

Abroad, there are three core conditions that help young researchers feel secure in staying: a visa, a good income, and insurance.

Dr. Pham Sy Hieu, Researcher at the Institute of Materials Science, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, holds two doctoral degrees: one in Chemistry from the University of Artois (France) and a Doctor of Science degree from the University of Mons (Belgium).

This young PhD believes that in the story of "returning home" after studying abroad, the group who go on scholarships plays a special role. These individuals have their tuition and living expenses covered by the State or international schools and often have a commitment to return and serve their country.

However, a problem also arises: many people, upon returning, are not suited to their positions. This is because the training environment abroad is often highly academic, while research conditions and facilities in Vietnam do not yet meet these requirements.

This has discouraged many people, making research projects difficult or impossible to carry out, leading to some cases where individuals seek to reimburse costs in order to leave their positions.

In the story of returning talent, financial considerations are one of the key factors determining the ability to retain talent.

At the 6th Global Forum of Young Vietnamese Intellectuals, which opened on the morning of July 19th in Hanoi, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Le Thi Thu Hang proposed abolishing the "salary ceiling" regulation in public institutions, especially universities and research institutes, in order to attract and retain Vietnamese intellectuals abroad to return and contribute to the country.

According to Deputy Minister Hang, in order to achieve breakthroughs in science, education, and digital transformation, Vietnam needs a new recruitment and compensation mechanism – one that is not rigidly based on ranks, grades, and coefficients, but rather flexible and competitive.

She also suggested encouraging non-discrimination between the public and private sectors, as both contribute to the overall development of the country.

These recommendations also reflect the reality that young scientists, such as Dr. Can Tran Thanh Trung, have observed and experienced. Dr. Trung points out a difference between Vietnam and developed countries, which is the mechanism for postgraduate training.

In the US, doctoral programs typically last 5 to 6 years with full scholarships, allowing students to fully dedicate themselves to research as a stable career.

In his final year of his PhD program, Trung received a postdoctoral scholarship sufficient to cover his living expenses, allow him to focus on his research, and even save money each month.

This model helps researchers feel secure in committing to long-term projects. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, this mechanism is still quite new.

Dr. Trung cited the example of the United States – where the young Vietnamese man had the opportunity to study and conduct research – where some professors take years off from teaching to focus on research, while still receiving a stable salary.

"For large-scale and ambitious projects, the timeframe can extend to 8-10 years, requiring a long-term financial investment strategy to allow scientists to fully dedicate themselves to the research," Dr. Trung shared.

According to Dr. Trung, recently, some universities have begun to pioneer the application of a combined teaching and research salary model for lecturers, aiming to improve the financial situation for scientists.

Based on practical experience, Dr. Pham Sy Hieu believes that: "Separating these two salary components is often seen in financially independent schools as a policy to retain talent."

At the same time, Dr. Hieu also believes that only when scientists solve the problem of basic necessities can they achieve stable and long-term development.

According to Clause 3, Article 4 of Circular 20/2020/TT-BGDĐT, the standard teaching hour quota for lecturers in Vietnam for one academic year ranges from 200 to 350 standard hours, equivalent to 600-1,050 administrative hours, nearly double that of France (190 hours) and significantly higher than that of the US and Germany (120-180 hours).

When teaching occupies a large portion of the time, the time available for research and pursuing long-term scientific projects is significantly reduced.

Dr. Thai Mai Thanh offered a comparative perspective, arguing that the model of focusing solely on full-time research is typically only found in universities ranked among the top 100 in the world.

"Even at top 200 universities, professors still have to teach multiple subjects, just like my professor in South Korea still teaches 3-4 subjects a year," Dr. Thanh cited as an example.

Dr. Thanh currently teaches three subjects per year. He believes that scientists need to combine teaching and learning, but at a reasonable and balanced level.

By dedicating time to teaching, scientists are also passing on knowledge and experience to future generations, creating value alongside their research work.

The young doctor shared that, in science, focusing solely on research is very stressful.

If results cannot be "measured" in terms of products or announcements, it is difficult to prove their value, because every investment must be transformed into concrete, applicable results that benefit the community.

According to Dr. Thanh, scientists should also put themselves in the position of managers to understand this pressure.

"Even when research projects or studies are unsuccessful or stalled, we can still create value in terms of teaching," Dr. Thanh expressed.

According to Dr. Hieu, besides the issue of remuneration, administrative procedures also become a major obstacle for scientists, preventing them from dedicating themselves wholeheartedly to research.

"When working abroad, I only focus on research; the procedures are handled by the assistants and secretaries of the research center," Dr. Hieu shared.

Conversely, domestically, researchers have to handle everything themselves: from securing research projects and implementing them to disbursing funds.

Each topic or project requires a specific set of documents and administrative procedures, along with confirmation from the managing agency.

"It's very difficult for scientists who constantly have to deal with bureaucratic procedures to concentrate on their research," Dr. Hieu shared.

According to Dr. Thai Mai Thanh, Vietnam is currently investing heavily in scientific research projects, especially those funded by the government.

However, from the perspective of a young scientist who has experience in international research systems, Dr. Thanh sees a significant barrier: young talents find it almost impossible to compete for these large project slots.

In many countries, the research funding allocation system is divided into several distinct levels.

Dr. Thanh gave an example: "About five years after graduating with a PhD, there will be a separate 'playing field' for young scientists, where they compete with their peers to win funded projects."

With an additional 5-10 years of postdoctoral experience, they can access higher-level projects with larger funding sources.

After about 15 years of experience, they become qualified to participate in very large-scale projects that require strong management skills and extensive research experience.

In Vietnam, this mechanism is virtually non-existent. This makes it difficult for young scientists who have recently returned to the country to compete with their seniors who have been with the system for many years.

When applying to scientific councils or project review committees, young candidates have little standing in terms of both experience and achievements, leading to a very low chance of receiving funding.

Dr. Thanh argues that this policy inadvertently creates psychological and career barriers, causing many young people who have completed their studies abroad to hesitate or even abandon the idea of returning home.

"What I want to convey is to give young people a real chance to try and take risks. Society often expects young people to succeed immediately, but the nature of research is about experimentation and learning."

Experienced scientists have the foundation to guarantee results. Meanwhile, young people may lack experience but are rich in new ideas and willing to try bold approaches.

"If there is a good monitoring mechanism along with clear requirements regarding progress and objectives, then even if the results do not meet expectations, the accumulated value from the research process is still very great," Dr. Thanh expressed.

Dr. Thanh believes that if Vietnam categorizes projects according to career stages, provides reasonable financial support, and ensures transparent supervision, more young scientists will be willing to return, bringing with them knowledge and enthusiasm to contribute.

Content: Linh Chi, Minh Nhat

Photos: Hung Anh, Thanh Binh, Minh Nhat

Design: Huy Pham

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/loi-gan-ruot-cua-nhung-nhan-tai-chon-tro-ve-20250828225942356.htm

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

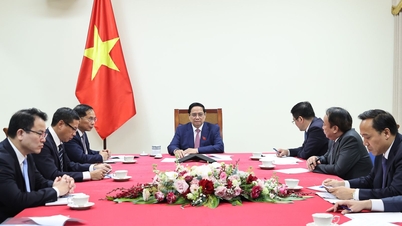

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh holds a phone call with the CEO of Russia's Rosatom Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765464552365_dsc-5295-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[OFFICIAL] MISA GROUP ANNOUNCES ITS PIONEERING BRAND POSITIONING IN BUILDING AGENTIC AI FOR BUSINESSES, HOUSEHOLDS, AND THE GOVERNMENT](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/11/1765444754256_agentic-ai_postfb-scaled.png)

Comment (0)