Even today, I still remember the words of General Dương Văn Minh and Brigadier General Nguyễn Hữu Hạnh spoken on Saigon Radio at 9:00 AM on April 30, 1975: "...we request all soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam to remain calm, cease fire, and stay where they are to hand over power to the revolutionary government in an orderly manner and avoid unnecessary bloodshed of our compatriots."

It was a joy that the war ended in an instant, the people of Saigon were safe, and the city remained intact.

On the afternoon of April 30th, I left my home in District 3 to visit my mother in Thi Nghe.

My family has nine brothers, and five of them served in the South Vietnamese Army: one became a disabled veteran in 1964, one died in 1966, one was a sergeant, one was a private, and one was a lieutenant.

My two older brothers had already received their military numbers; only my adopted younger brother and I were left without them. That afternoon, when my mother saw me, she choked back tears and said, "If the war continues, I don't know how many more sons I'll lose."

Leaving my mother's house, I went to Phu Tho University of Technology (now Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology) to check out the situation.

At the time, I was the third-highest ranking person on the school's leadership team, whose leader had gone abroad a few days earlier.

Upon entering the gate, I saw several staff members wearing red armbands standing guard to protect the school. I was relieved to see that the University of Technology was intact and safe.

It's hard to describe the joy of seeing peace coming to our country, but even 50 years later, I'm still happy. By 1975, the war had lasted 30 years, longer than my 28 years of age at the time. Our generation was born and raised in war; what greater joy could there be than peace?

After the joyful days of peace and reunification came countless hardships. The economy declined, life became difficult, and the border wars in the Southwest with the Khmer Rouge and the 1979 border war in the North with China left many people feeling gloomy, and many chose to leave.

I still try to remain optimistic about the country's peace; after all, I'm still young and can endure hardship. But looking at my child, I can't help but feel heartbroken. My wife and I had another daughter at the end of November 1976, and our child didn't have enough milk, so my father-in-law gave his ration of milk to his granddaughter.

Our government salaries weren't enough to live on, so we had to gradually sell off whatever we could. My wife taught English at the Banking University, at the Polytechnic Training Center of the Patriotic Intellectuals Association, and also gave extra lessons at many private homes, cycling dozens of kilometers until late at night.

As for me, I cycle early in the morning to drop my two children off at their grandmother's house in Binh Thanh District, then head to the Polytechnic University in District 10 to teach. At noon, I return to drop my son off at Le Quy Don School in District 3, then go back to work at the university.

In the afternoon, I would return to Binh Thanh District to pick up my daughter, then go back to our house in Yen Do residential area, District 3, where my wife would pick up our son. I cycled more than 50km every day like that for several years. In the early 1980s, I lost more than 15kg, becoming as thin as I was when I was a student.

Difficulties and shortages were not the only sad things; for us intellectuals from the South, the mental storm was even more serious.

At 28 years old, having returned to Vietnam less than a year after seven years of studying abroad, and holding the position of assistant dean at the then University of Technology - equivalent to the vice-rector of the current Polytechnic University - I was classified as a high-ranking official and had to report to the Military Governing Committee of Saigon - Gia Dinh city.

In June 1975, I was ordered to attend a re-education camp, but I was lucky. On the day I arrived, there were too many people, so it had to be postponed. The next day, an order came that those in the education and health sectors who had to attend re-education camps would have their rank reduced by one level, so I didn't have to go.

One by one, my friends and colleagues left, in one way or another, for one reason or another, but everyone carried with them sadness, everyone left behind their ambitions. By 1991, I was the only PhD holder trained abroad before 1975 at the Polytechnic University who remained to teach until my retirement in early 2008.

Having been associated with Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology for over 50 years, sharing in its historical journey and experiencing both joy and sorrow, even bitter moments, I have never regretted my decision to leave a comfortable life and a promising scientific future in Australia to return home in 1974 and remain in Vietnam after 1975.

I chose to work as a university lecturer with the desire to share my knowledge and understanding with university students, contributing to the development of the country and finding peace of mind through dedication to my homeland and fulfilling the responsibility of an intellectual.

For 11 years as head of the Department of Aeronautical Engineering, laying the foundation for the development of human resources in Vietnam's aerospace engineering industry, I have contributed to training over 1,200 engineers, of whom more than 120 have gone on to pursue doctoral degrees abroad.

It is an even greater joy and source of pride that I was involved in initiating the "For a Developed Tomorrow" program of Tuoi Tre newspaper, starting in 1988, and since then I have been a "pioneer" in empowering many generations of students.

Regarding the "Supporting Students to School" scholarship program, I have been in charge of fundraising for the Thua Thien Hue region for 15 years. Tens of thousands of scholarships, totaling hundreds of billions of VND, have opened up future opportunities for tens of thousands of young people.

By contributing to Vietnam's future, the loneliness I felt during the difficult days after 1975 has gradually faded away.

Thirty years of war left millions of families with heartbreaking losses and left behind deep-seated hatred, prejudice, and misunderstandings. Fifty years of peace, sharing a common Vietnamese home, working together towards a common goal for the country's future, has allowed kinship to resolve hatred and prejudice.

For many years, I found myself caught in the middle: domestically, I was seen as a supporter of the old South Vietnamese regime; abroad, I was perceived as a supporter of the socialist regime. By calmly choosing my ideals to be for my country, my way of life and work naturally became a bridge between the two sides.

Over the past 50 years of peace and reunification, I have forged many close relationships between people on "this side" and "that side," and I am truly proud to have been a part of national reconciliation and harmony.

On the altar in my grandmother's house in Hue, there are three sections: in the middle, high up, are the portraits of my great-grandparents and later my paternal grandparents; on one side are the portraits of my paternal grandparents' children who served in the Liberation Army; and on the other side are the portraits of other children who served in the South Vietnamese Army.

My grandmother had poor eyesight, and in her final years, her vision deteriorated. I think this was partly a consequence of the years she spent weeping over her children who died in the war.

In front of the house were two rows of betel nut trees and a small path leading to the gate. I imagined my grandparents standing at the gate, waving goodbye to their children going to war; I also pictured them sitting on chairs on the porch in the evenings, gazing into the distance, waiting for their children's return; and it was there that I witnessed the heartbreaking scene of elderly parents weeping for their young children in immeasurable grief.

Only countries that have experienced war, like Vietnam, can truly understand the long, agonizing wait of wives and mothers whose husbands and sons are away for extended periods. "The desolate twilight is tinged with purple, a twilight that knows no sorrow. The desolate twilight is tinged with a poignant sadness" (Huu Loan).

Women's fates during wartime were all the same; my mother followed in my grandmother's footsteps. My father "went away as soon as we got married," and each time he came home on leave, my mother was pregnant.

I think during those years, my father also worried about his wife's childbirth at home, wondering how things would go and whether the children would be born healthy. My mother single-handedly raised the children.

Once, while hurrying home on foot before curfew, a grenade exploded near my feet; luckily, I was only injured in the heel.

My mother's generation was luckier because they only had to wait for their husbands, and even luckier because my father returned, and they had a reunion, not having to go through the sadness like my grandmother, "sitting beside her child's grave in the darkness."

My family's story isn't unusual. Several times, reporters have offered to write about the children on either side of my grandparents' families, but I declined, because most families in the South share similar circumstances. My family has experienced less heartbreak than many others.

I've visited war cemeteries across the country, and I've always pondered the immense pain behind each tombstone. I once visited Mother Thu in Quang Nam when she was still alive. Later, every time I looked at Vu Cong Dien's photograph of Mother Thu, with teary eyes, sitting before nine candles symbolizing her nine sons who never returned, I wondered how many other mothers like Mother Thu there were in this S-shaped land of Vietnam.

During decades of peace, even though we had enough to eat, my mother never wasted any leftover food. If we didn't finish it today, we'd save it for tomorrow. It was a habit of saving from a young age, because "throwing it away is wasteful; we didn't have enough to eat in the past." "In the past" were the words my mother mentioned most often, repeating them almost every day.

What's remarkable is that when she talks about the old days – from the years of artillery fire to the long years of scarcity, with rice mixed with sweet potatoes and cassava – my mother only reminisces, never complains or laments. Occasionally, she laughs heartily, surprised that she managed to get through it all.

Looking back, the Vietnamese people, having gone through war and hardship, are like rice seedlings. It's unbelievable where they got such resilience, endurance, and perseverance from such small, thin bodies, where hunger was more common than satiety.

Fifty years of peace have passed in the blink of an eye. My grandparents are gone, and my parents have also passed away. Sometimes I wonder what my family would be like if there hadn't been a war. It's hard to imagine with the word "if," but surely my mother wouldn't have that wound on her heel, my parents wouldn't have had those years of separation, and the ancestral altar of my paternal family would be adorned with the same colored robes...

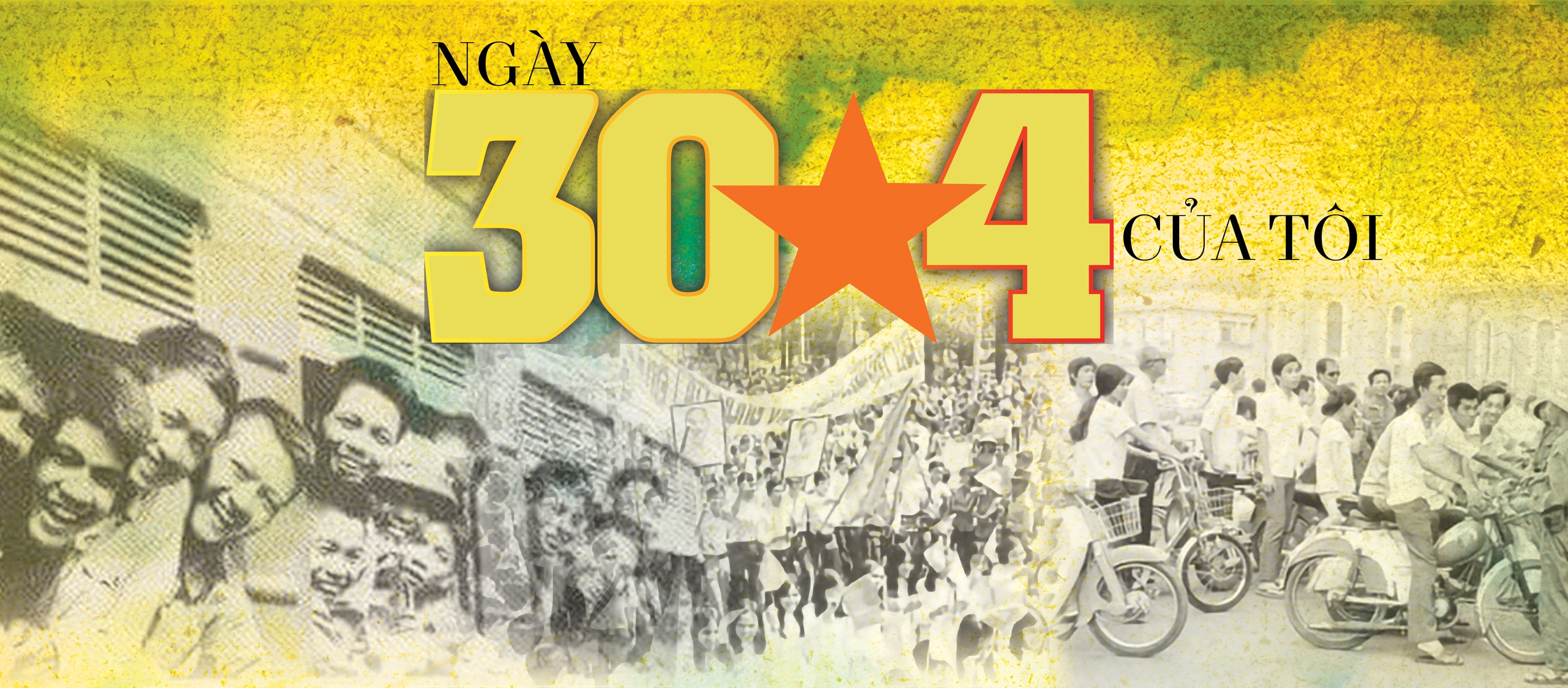

After the fall of Buon Ma Thuot, time, like a galloping steed, surged forward, heading straight towards a day that perhaps no Vietnamese person will ever forget: Wednesday, April 30, 1975.

Within a few dozen days, developments on the battlefield and in the political arena made it clear that South Vietnam would fall. My family's acquaintances were divided into two groups: those frantically arranging plane tickets to flee Vietnam and those calmly observing the situation. The latter group was far larger than the former.

On April 29th, the fighting seemed to have subsided, but the city center became chaotic. People rushed to Bach Dang Wharf and the US embassy, scrambling to find a place to leave.

On the morning of April 30th, news poured in. In the alleys in front of and behind my house, people were shouting and spreading the news through megaphones.

From early morning:

"They're coming down from Cu Chi."

"They've arrived at Ba Queo."

"They're going to Bay Hien intersection," "They're going to Binh Chanh," "They're going to Phu Lam"...

A little after noon:

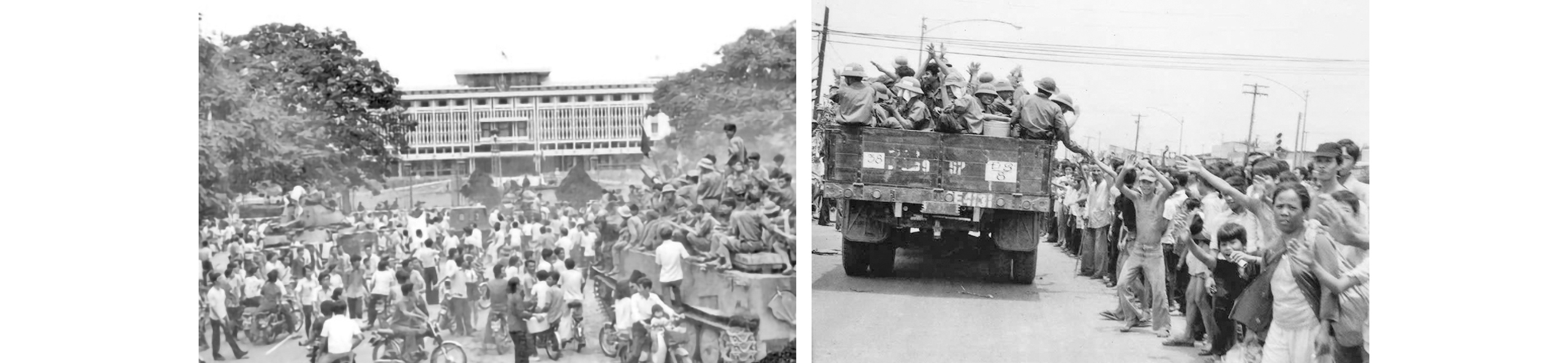

"Their tanks are heading to Hang Xanh", "Their tanks are heading towards Thi Nghe", "Tanks are on Hong Thap Tu Street from the Zoo towards the Independence Palace".

"They're turning into the Independence Palace. Oh no, it's all over!"

The events that followed that morning simply formalized the end of the war. President Dương Văn Minh announced the surrender on the radio.

Some people panicked. However, most families in the neighborhood observed quietly and relatively calmly.

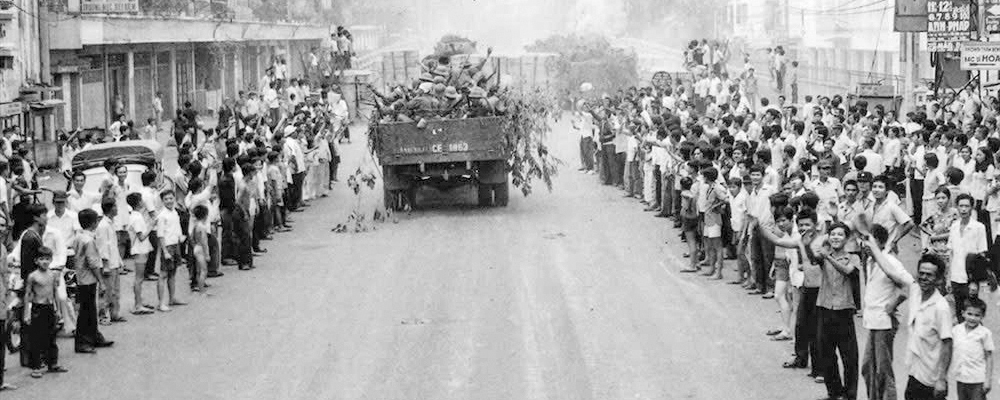

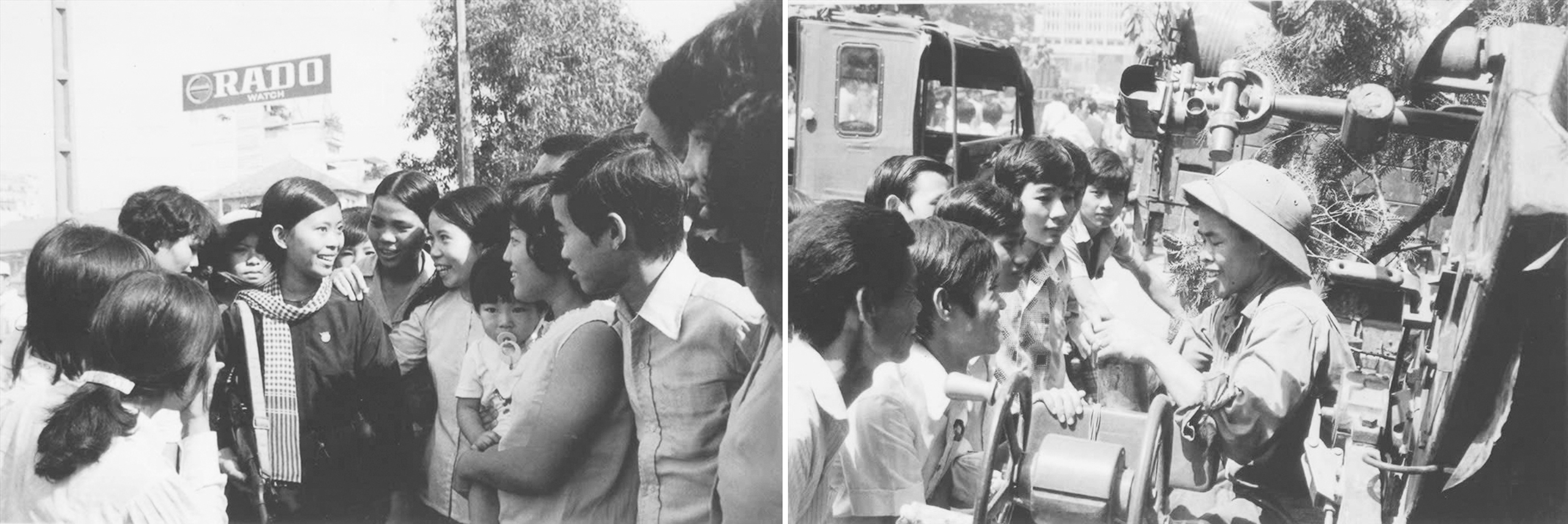

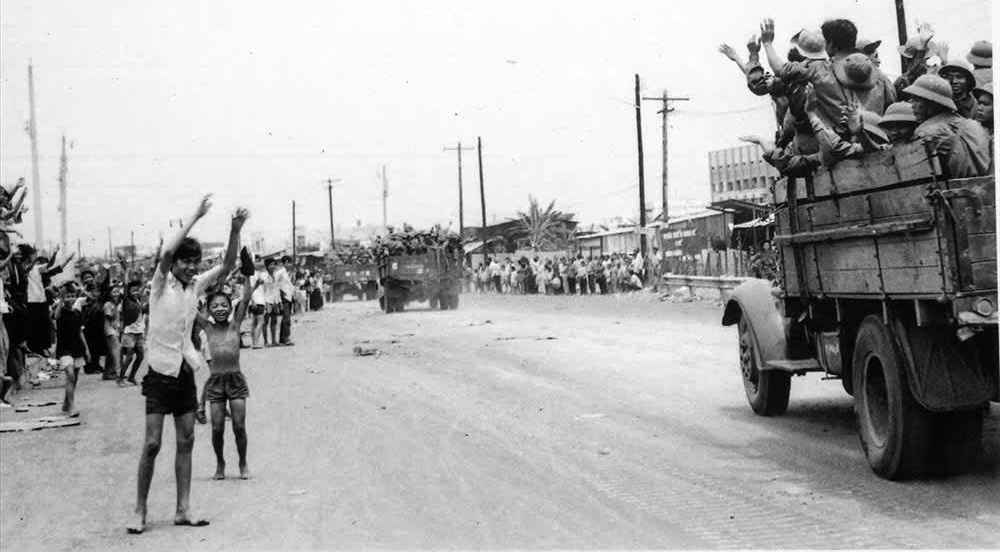

By late afternoon on April 30, 1975, people had begun opening their doors to greet each other. Saigon residents were accustomed to political upheavals, so most were temporarily reassured by the changes they didn't fully understand.

That evening, my father held a family meeting.

My father said, "I think it's good that they've taken the city. This war was huge and long, and it's great that it ended so peacefully. Anyway, the reunification of the country is the most welcome thing!"

My mother said: "No one wants the war to drag on. Now your parents can rest assured that your generation will live a happier life than we did."

Amidst such hopes and anxieties about the distant future, my family also found that the takeover generally went smoothly, with the new government demonstrating goodwill in preventing looting and restoring order and social stability.

In the first days of May 1975, the streets were deserted, like during the Lunar New Year, and had lost their usual neatness. An entire army of several hundred thousand men from the South Vietnamese regime, who had been discharged the day before, had vanished without a trace.

I wandered around Saigon and came across garbage dumps littered with hundreds of brand-new military uniforms hastily discarded, thousands of perfectly good pairs of boots lying around unattended, countless berets and water canteens lying haphazardly... Sometimes I even encountered disassembled guns and a few grenades scattered on the roadside.

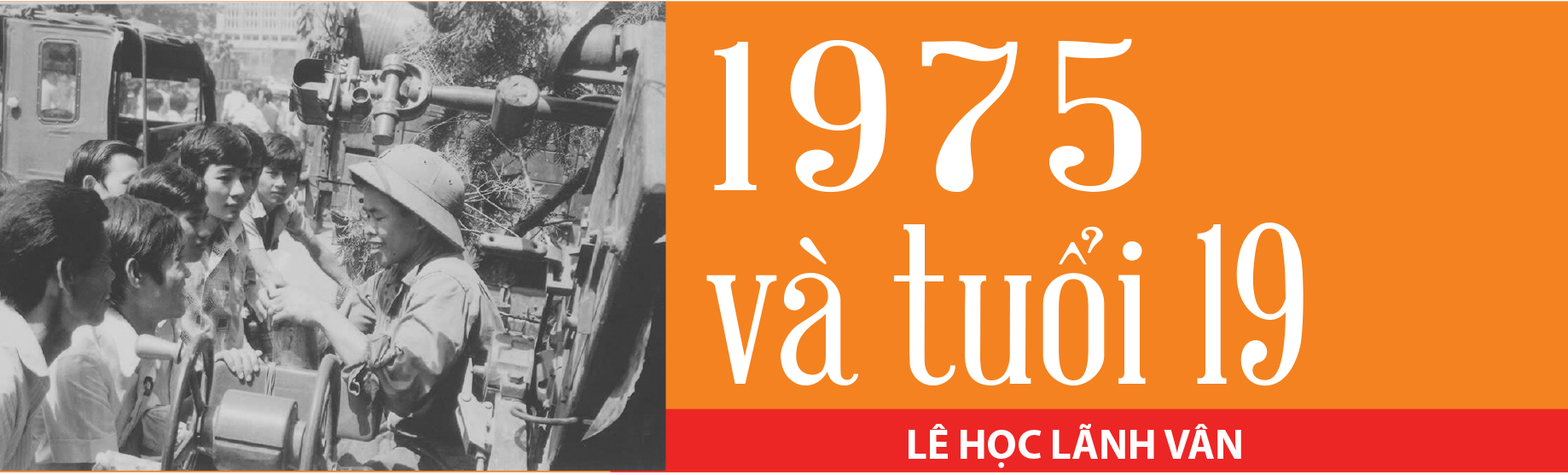

Along the way, we occasionally encountered a few North Vietnamese military vehicles, still covered in camouflage leaves. Everywhere we went, we saw gentle-looking soldiers with wide, bewildered eyes, observing, curious, inquiring, and fascinated.

The initial sense of security and goodwill caused support to outweigh opposition, enthusiasm to outweigh indifference. What was certain was that there was no more war.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Contents: NGUYEN THIEN TONG - NGUYEN TRUONG UY - LE HOC LANH VAN

Design: VO TAN

Tuoitre.vn

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/ngay-30-4-cua-toi-20250425160743169.htm

![[Image] Spectacular performances at the Light Concert celebrating the New Year 2026](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F02%2F01%2F1769901942536_image.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![[Image] Spectacular performances at the Light Concert celebrating the New Year 2026](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F02%2F01%2F1769901942536_image.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 3] Ultra-thin rice paper takes off.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F28%2F1769562783429_004-194121_651-081010.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![OCOP during Tet season: [Part 2] Hoa Thanh incense village glows red.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F402x226%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F27%2F1769480573807_505139049_683408031333867_2820052735775418136_n-180643_808-092229.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)