A recent two-day meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, brought together journalists and academics from around the world to discuss how to implement those rules and agree on principles that could help shape legislation. So far, more than 50 organizations have signed on to the principles.

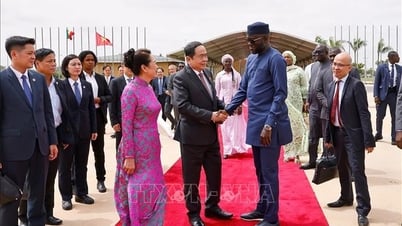

The world of journalism is putting pressure on tech companies to pay for using news to make a profit. Photo: Poynter

The war of the press world

In the spring of 2021, Australia passed a “world-first” law aimed at addressing the unfair relationship between big tech giants and news publishers. Since then, about $140 million has been paid to Australian news organizations. Canada then passed Bill C-18 in June, and the UK is likely to adopt new competition rules by the end of 2023. Indonesia’s president is expected to issue a decree that would force social media and tech platforms like Facebook and Google to pay for news.

The US is lagging behind in this fight, as the bipartisan Journalism Competitiveness and Preservation Act has yet to be passed. The conference, “Big Tech and Journalism,” organized by Michael Markovitz of the GIBS Media Leadership Think Tank, is an effort to help policymakers and stakeholders craft agreements that improve on what Australia and Canada have done.

A statement of global principles drafted at the meeting calls for more transparency on how fees are calculated, including for smaller news outlets, and how the money received is spent on journalism.

“Both platforms and publishers should adopt the highest possible level of transparency so that all parties can assess the fairness of any arrangement and so that third parties can assess the full impact of the mechanism. For example, mechanisms could require platforms and publishers to share data on their scale and operations, as well as their ad placements,” reads section 7 of the principles.

Many journalists from Latin America and Africa who attended the meeting were intrigued by the new rules but still had concerns about who would ultimately receive money from Google and Meta. They wanted to ensure that any compensation mechanism accurately reflected the true value of news, and that real news was distinguished from regurgitated news, and especially from news that had been “remixed” by artificial intelligence from original sources.

Need solidarity of all

Transparency has long been a sticking point, with news organizations around the world that receive money from Google and Meta signing non-disclosure agreements. The secrecy has hurt smaller news organizations because they don’t know how to price and what they can ask for.

Google is also striking deals in countries without bargaining rules. In Taiwan, Google negotiated a three-year deal with news organizations worth just $10 million, after facing pressure from a regulation similar to Australia’s.

In South Africa, Google has not provided details of the discussions, but several news organizations have been told by Google that the company will work directly, through the Google News Showcase project, as it does in Australia, with the 10 largest publishers and others will be covered by a fund created by Google.

Because the agreements between Google or Meta and news organizations are confidential, it is unclear exactly how they work. Publishers say they do not receive direct payments, but are paid in technology products and some form of service fee.

In Australia, publishers have said it's a "joke." In Brazil and Spain, the payments come in the form of having their news prioritized by Google through its "Google Discover " channel, a personalized news feed aimed at advertisers.

In South Africa, there is some division among news organizations, with the South African National Editors Forum and others asking Google to only fund news organizations that are members of the South African Press Association. Some sources say Google has agreed to that condition.

Against this backdrop, efforts are being made to prevent fragmentation in the media industry, in order to counter the misconception that only large or established media benefit from these efforts.

“If you move together, they can’t divide you,” said BBC Media Action’s Helena Rae, who is working with Indonesia’s Press Council on a bill modelled on Australia’s.

Nelson Yap, publisher of the Australian Property Magazine, a small specialist news outlet in Australia, has been talking to fellow media leaders around the world about the importance of sticking together. “Publishers of all sizes need to band together,” Yap advises.

How to calculate?

But even if news organizations were granted collective bargaining rights, they would struggle to value their products. How valuable is news on Google or Facebook? Should that value be determined by traffic? And what data do policymakers have to make decisions?

Google and other tech platforms are reaping huge benefits from press coverage, but have always shied away from sharing the profits. Photo: GI

As part of the pricing process, news organizations around the world are looking at ways to pay for it. In Switzerland, news organizations hired a leading behavioral economist to help them determine the value of news in Google search. The results were presented at a conference and received acclaim for their efforts to objectively determine the value of news to platforms.

Research by Fehr Consulting found that when Google searches did not include news, users reported a less satisfying experience and did not return to the site. Using this user behavior research, the economists argued that the presence of news created value for Google, calculating that Swiss publishers would receive 40% of the advertising, or about $166 million.

As such, a global standard for what tech giants like Google and Meta “owe” news organizations is emerging. Journalism associations in several countries have begun calculating what they believe the tech giants owe them.

In addition, policymakers in many countries are increasingly concerned with addressing the weakening of journalism relative to social media and technology platforms that are floating and very little controlled on the internet space.

Hoang Hai (according to Poynter, Cima, FRL)

Source

Comment (0)