Prices of benchmark Thai white rice (5% broken) have increased by 22% since India’s ban on non-basmati white rice exports came into effect in July 2023. Global supplies have been disrupted as exports of each of India’s restricted products – non-basmati white rice, parboiled rice and broken rice – have all fallen sharply over the same period.

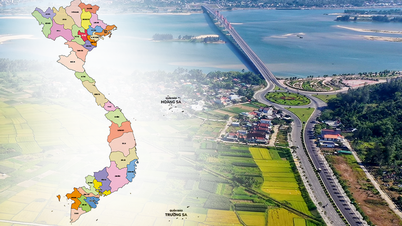

This has left importing countries in South Asia, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa struggling, forcing them to look for alternative sources even as other major rice exporters including Vietnam and Thailand face production losses due to the impact of El Niño.

|

| Illustration |

Global rice production and El Niño

Production is relatively stable worldwide, in part due to the drying effects of El Niño on key producers in Asia. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that global rice production in marketing year 2023/24 will exceed the previous year’s level by about 583,000 metric tons (MT)—an increase of only about 0.1%.

Despite this slight increase, rice exports are still down 3.8 million tonnes, down 5% from last year’s levels. Exports from Pakistan, the US and Myanmar are up by a combined 2 million tonnes, while the combined declines from major exporters such as India, Vietnam and Thailand are down by 5.5 million tonnes. India’s rice exports are down 4.2 million tonnes in 2023/24, down 21%.

Among the top six exporters, Pakistan’s production is estimated to increase by around 3.5 million tonnes (up 64% from last year’s flood-affected crop) while US rice production is up 1.9 million tonnes (up 32% due to higher plantings and yields this year compared to last year) and Myanmar’s output is up 150,000 tonnes (up 1.3%). But these increases are partially offset by El Niño-related production losses in India (down 3.8 million tonnes or -2.8%) and Thailand (down 900,000 tonnes or -4.3%).

On a positive note for global production in the near term, El Niño’s impact on crop conditions in rice-producing countries in South and Southeast Asia was generally favorable through late January, with the exception of dry conditions in southern India. El Niño diagnostic (ENSO) models suggest that the current El Niño may still impact the February-April season in Southeast Asia, but it is expected to weaken significantly over the next few months as Pacific ocean temperatures transition to ENSO-neutral conditions in April-June.

Indian rice exports fall

Amidst this already uncertain global supply situation, India’s export restrictions have added to the market’s stress. India began an escalating round of rice export restrictions in August 2022, banning broken rice exports and imposing additional duties on non-basmati white rice exports (excluding parboiled rice). This was followed by a ban on non-basmati rice in July 2023, followed by further restrictions on basmati and parboiled rice in August.

Broken rice exports are expected to decline in the last quarter of 2022, especially to China (which imports broken rice for animal feed). While exports continue throughout the first half of 2023 to important West African markets such as Senegal, they have been negligible since July 2023. India exported just 28,500 tonnes of broken rice between August and November 2023, down 95% year-on-year. The ban on non-basmati white rice has also led to a similar decline in export volumes. Non-basmati white rice exports totaled around 154,000 tonnes between August and November 2023, down 93%.

Parboiled rice exports, which were not affected by the measures in July, rose 39% in August as exporters switched products to cover losses. In response, India imposed an additional 20% duty on parboiled exports in the same month. Parboiled rice exports fell 69% in September. India’s rice exports totaled 3.7 million tonnes in August-November 2023, down 46% year-on-year. Only basmati rice exports increased, up 12% in August-November 2023 compared to 2022. As a result, India’s rice exports fell in most major markets.

The regions that saw increases (North America, Northern Europe, Southern Africa) were those dominated by basmati rice. But most regions where India’s major rice imports were subject to export restrictions saw declines of 50% or more year-on-year, especially Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, India’s rice exports to West Africa fell by about 1.2 million tonnes, or 54%, while India’s rice exports to countries in East and Central Africa fell by 58% and 80%, respectively.

Are importing countries looking for alternative sources of rice?

India is an important source of rice globally, especially for countries in Africa. How are African countries coping with the loss of imports from India? A comprehensive analysis is difficult due to the relative paucity of monthly import data from many countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, it is possible to focus on three important importers of Indian rice in Africa for which import data are available—Madagascar, Kenya, and Senegal—to better understand the impact of India’s trade practices.

Madagascar’s rice imports from all sources are expected to average 425,000 tonnes in 2023, down 44% from 2022 levels and down 32% from the 2020-22 three-year average. About 80% of the country’s rice imports come from India in the form of non-basmati, unparboiled rice. Since August, most of the country’s rice imports have come from Pakistan.

In the first seven months of 2023, Kenya imported 817,000 tonnes of rice, nearly 70% of which came from India. After the restrictions took effect, rice imports dropped to almost zero. Pakistan had previously been a significant supplier, but imports did not increase (until November 2023) to make up for the drop. Senegal is a major importer of broken rice, which is used in traditional cuisine such as thiéboudienne, a rice and fish dish.

In recent years, India has been the main supplier of broken rice to Senegal, accounting for 64% of total imports in 2022 and over 80% of imports in the January-August 2023 period. Since September, broken rice imports from India have increased and decreased by more than 50%. Senegal has been able to partially offset this decline by increasing broken rice imports from Thailand and Brazil.

The global rice market is in turmoil as El Niño impacts output in South and Southeast Asia and India’s exports are cut in half. Rice-importing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, which have been hardest hit, are scrambling to find alternatives, even as global rice prices have risen more than 20% since India imposed restrictions. However, forecasts that the current El Niño will weaken in the coming months offer some hope for improved future production prospects.

The key question is how long will India’s export restrictions remain in place? India is considering extending the 20% tariff on parboiled rice beyond its March 31 expiration date. Some speculate that nothing will change until after India’s general election in late spring. Given this uncertainty, if India’s exports continue at their current pace (50% of normal) after the election, it seems likely that global export forecasts will have to be revised downward, potentially leading to higher prices and more pressure on food security in rice-importing countries.

Source

![[Maritime News] More than 80% of global container shipping capacity is in the hands of MSC and major shipping alliances](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/16/6b4d586c984b4cbf8c5680352b9eaeb0)

Comment (0)