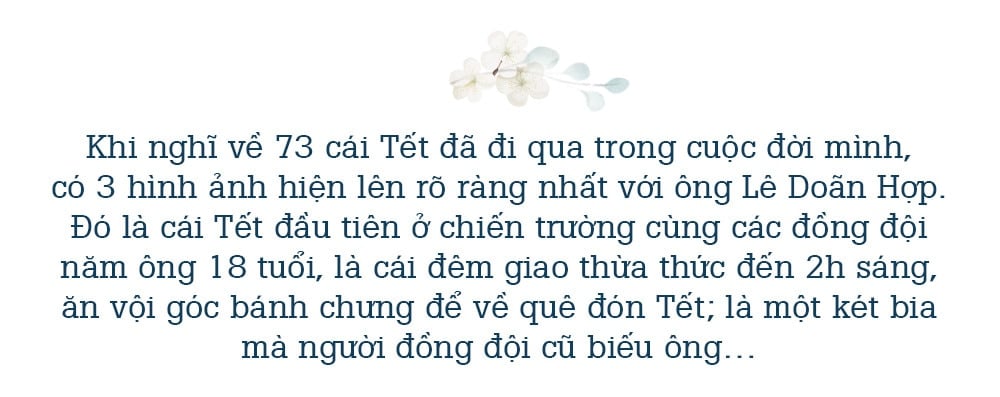

Talking with former Minister of Information and Communications Le Doan Hop on the occasion of the Year of the Dragon, summarizing the past year, he "boasted": "Last year, I flew 82 flights across the North and South". Although he has been retired for 12 years, he still writes poetry, writes books and is especially "in demand" going everywhere to talk and share. Before he retired, a reporter asked: "When you retire, where will you go?", he did not hesitate to answer: "I will go to a place that meets 4 conditions: has the most friends and colleagues; has the most children and grandchildren; has the best health care system and that must be the place where I have the most favorable opportunities to work in the media". He chose Hanoi as his "residence" for the last years of his life. But every time Tet comes, like every year, he returns to the house where he was born and raised in Nghe An. Only in the past 5 years, when his father passed away and his mother was weak, did he bring her to Hanoi to take care of her until she passed away. For him, "wherever mother is, there is Tet."

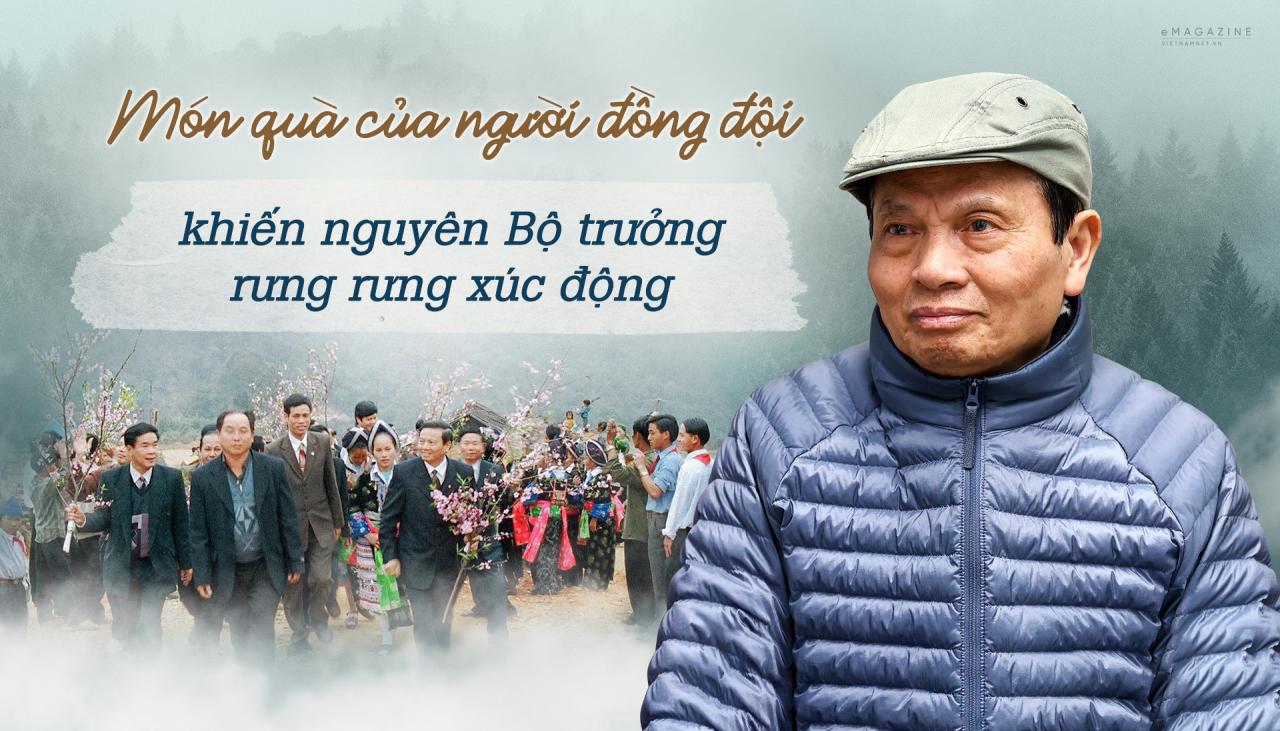

When asked about the Tet holidays he remembers the most, three images suddenly appeared in his memory. “That was Tet on the battlefield in the year of the Rooster 1969. At that time, I was 18 years old, the first time I was away from home, the first time I celebrated Tet on the battlefield in the Southeast region. In the blazing sun, I missed the cold, the drizzle of the North. The feeling of homesickness surged. We had no banh chung, no pork. We shared a cake of dry food, sat together and told stories about Tet in our hometown.” Recalling the Tet holidays of his childhood, he could not forget the image of poverty but full of humanity. “Tet in the past made people look forward to and wait because only on Tet could we have things that were never available on normal days.” “Only during Tet can we eat rice without additives. Only during Tet can we wear new clothes. During Tet, children can go out all day without being scolded by their parents. During Tet, no one speaks harshly to each other. All of these things create an extremely sacred atmosphere.” Remembering the anecdote about eating rice without additives, he shared a story he heard. “In 1961, Uncle Ho returned to Nghe An . He went down to the provincial party committee's dining room and saw only rice without additives. He asked: 'Doesn't our hometown eat rice without additives anymore?'. At that time, the provincial party committee secretary, Vo Thuc Dong, didn't know how to answer, but the catering lady quickly said a very truthful sentence: 'When you come back, the whole province is happy. We cook a meal without additives to celebrate. When you leave, our family will eat rice without additives to make up for it.'” That said, to know that, during those hungry and miserable days, eating a meal without additives was considered a celebration. But on Tet, not only do they not have to eat rice mixed with other ingredients, they also get a slice of banh chung, a piece of fish, or a piece of meat that they never have on normal days. All year round, children have to wait until Tet to have a new set of clothes to wear. "Sometimes they don't even dare to wear them because their friends' clothes are torn, and they feel ashamed when they wear new clothes." That's why he once wrote a few verses when remembering those difficult days: "I wish for a beautiful dress, which I only get once a year , waiting for the afternoon of the 30th of Tet , wearing it makes my heart flutter."

When asked about the Tet holidays he remembers the most, three images suddenly appeared in his memory. “That was Tet on the battlefield in the year of the Rooster 1969. At that time, I was 18 years old, the first time I was away from home, the first time I celebrated Tet on the battlefield in the Southeast region. In the blazing sun, I missed the cold, the drizzle of the North. The feeling of homesickness surged. We had no banh chung, no pork. We shared a cake of dry food, sat together and told stories about Tet in our hometown.” Recalling the Tet holidays of his childhood, he could not forget the image of poverty but full of humanity. “Tet in the past made people look forward to and wait because only on Tet could we have things that were never available on normal days.” “Only during Tet can we eat rice without additives. Only during Tet can we wear new clothes. During Tet, children can go out all day without being scolded by their parents. During Tet, no one speaks harshly to each other. All of these things create an extremely sacred atmosphere.” Remembering the anecdote about eating rice without additives, he shared a story he heard. “In 1961, Uncle Ho returned to Nghe An . He went down to the provincial party committee's dining room and saw only rice without additives. He asked: 'Doesn't our hometown eat rice without additives anymore?'. At that time, the provincial party committee secretary, Vo Thuc Dong, didn't know how to answer, but the catering lady quickly said a very truthful sentence: 'When you come back, the whole province is happy. We cook a meal without additives to celebrate. When you leave, our family will eat rice without additives to make up for it.'” That said, to know that, during those hungry and miserable days, eating a meal without additives was considered a celebration. But on Tet, not only do they not have to eat rice mixed with other ingredients, they also get a slice of banh chung, a piece of fish, or a piece of meat that they never have on normal days. All year round, children have to wait until Tet to have a new set of clothes to wear. "Sometimes they don't even dare to wear them because their friends' clothes are torn, and they feel ashamed when they wear new clothes." That's why he once wrote a few verses when remembering those difficult days: "I wish for a beautiful dress, which I only get once a year , waiting for the afternoon of the 30th of Tet , wearing it makes my heart flutter."  He called the Year of the Pig - the year he carried out his duties as Minister of Culture and Information - a Tet of dedication. On New Year's Eve that year, he initiated the implementation of art programs to celebrate spring on the streets around Hoan Kiem Lake. While his family was still in Nghe An, he stayed to directly direct and enjoy the art program until 2am. Before that, he told the driver to buy banh chung in advance because he knew that no one would sell anything the next morning. At 4am, the Minister and the driver sat down to cut banh chung and eat it, then got in the car and drove straight from Hanoi to his hometown to celebrate Tet with his family. He will probably never forget that memory of a leader's Tet, although it was hard but full of joy in contributing to the spiritual life of the people of the capital. He said, in the past, there was no such thing as going to wish superiors a happy new year, only wishing each other a happy new year. The cultural tradition of the Vietnamese people is to be grateful and repay gratitude. Knowing how to repay gratitude is culture and morality. “In the past, people only wished each other with words, not with material things. Tet gifts were the first kilo of sticky rice of the season, the basket of newly dug potatoes, the things they produced themselves, given to those who had done them a favor, those who had helped them in work and life.”

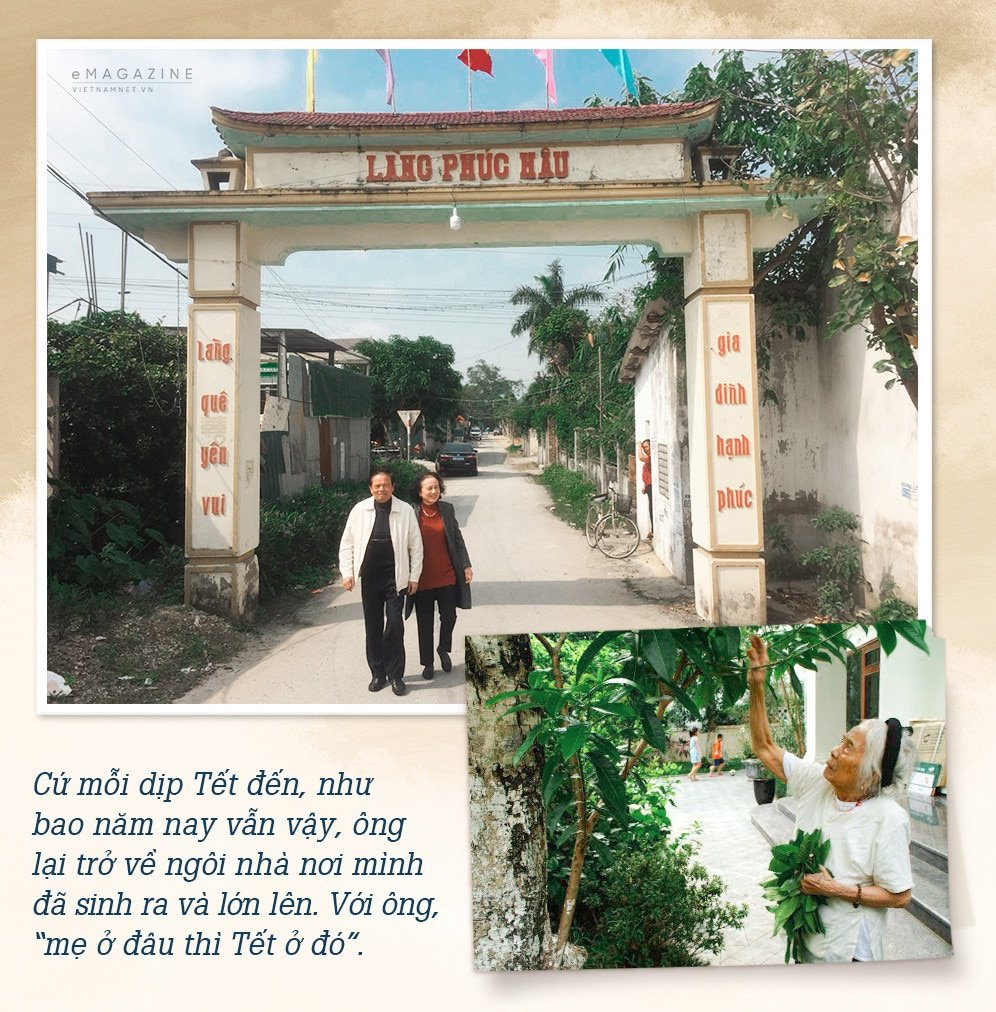

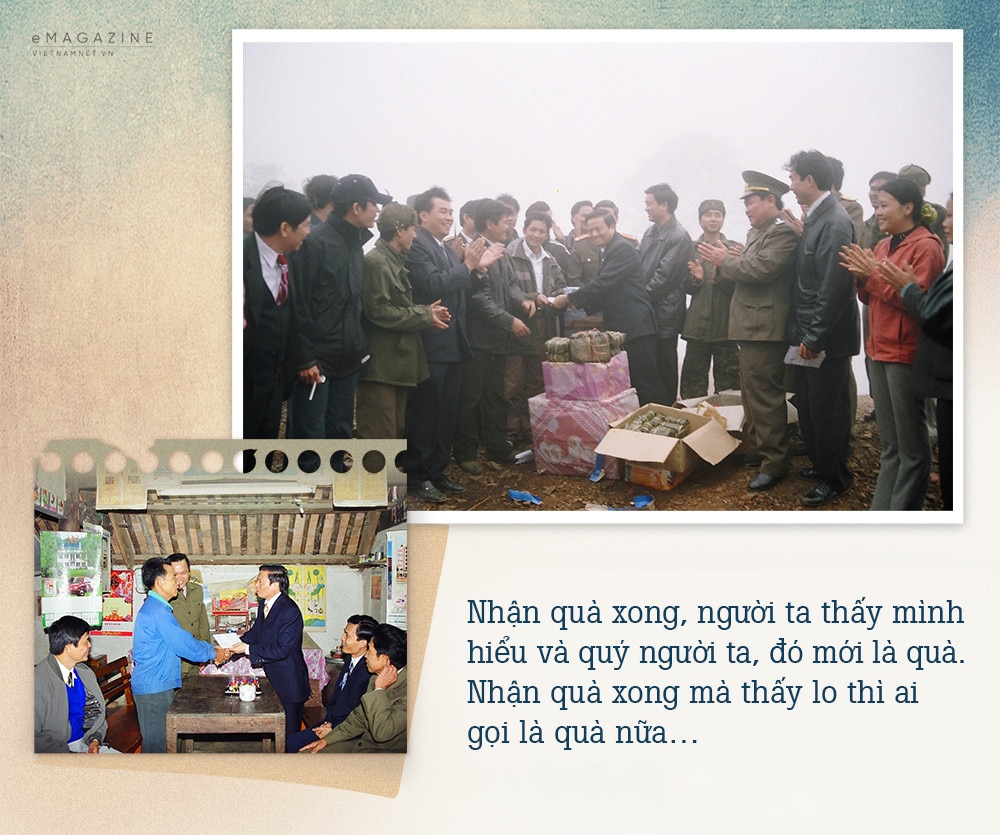

He called the Year of the Pig - the year he carried out his duties as Minister of Culture and Information - a Tet of dedication. On New Year's Eve that year, he initiated the implementation of art programs to celebrate spring on the streets around Hoan Kiem Lake. While his family was still in Nghe An, he stayed to directly direct and enjoy the art program until 2am. Before that, he told the driver to buy banh chung in advance because he knew that no one would sell anything the next morning. At 4am, the Minister and the driver sat down to cut banh chung and eat it, then got in the car and drove straight from Hanoi to his hometown to celebrate Tet with his family. He will probably never forget that memory of a leader's Tet, although it was hard but full of joy in contributing to the spiritual life of the people of the capital. He said, in the past, there was no such thing as going to wish superiors a happy new year, only wishing each other a happy new year. The cultural tradition of the Vietnamese people is to be grateful and repay gratitude. Knowing how to repay gratitude is culture and morality. “In the past, people only wished each other with words, not with material things. Tet gifts were the first kilo of sticky rice of the season, the basket of newly dug potatoes, the things they produced themselves, given to those who had done them a favor, those who had helped them in work and life.”  Mr. Hop said that during his time as an official, he also went to wish many people a Happy New Year, but he often chose "cultural gifts". "After receiving a gift, people feel that they understand and appreciate them. If they feel happy after receiving a gift, then that is a gift. If they feel worried after receiving a gift, then who would call it a gift anymore... And the recipient must also have a culture of receiving the gift so as not to offend the giver while still maintaining dignity and ethics. If you have contributed to the person, then accept it and only accept it within cultural and safe limits." According to him, Tet gifts are not material things but a signal that people think of each other during Tet. And thinking of each other is culture."

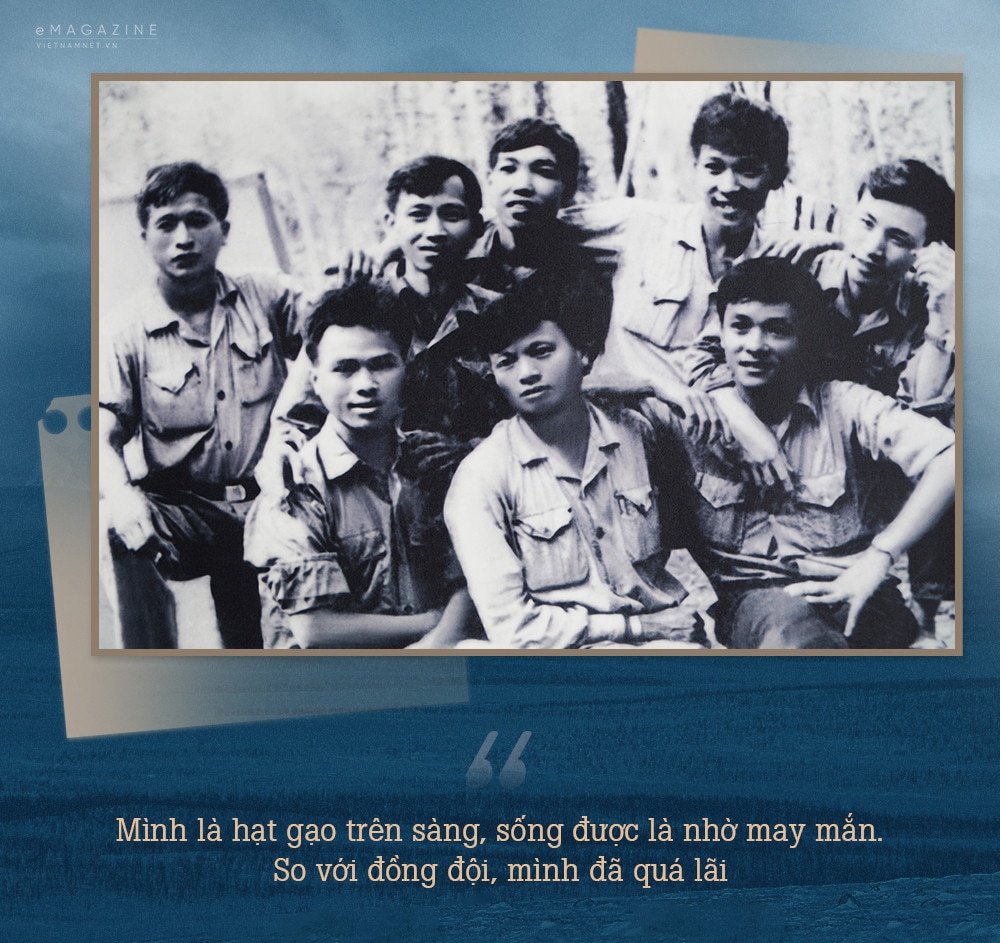

Mr. Hop said that during his time as an official, he also went to wish many people a Happy New Year, but he often chose "cultural gifts". "After receiving a gift, people feel that they understand and appreciate them. If they feel happy after receiving a gift, then that is a gift. If they feel worried after receiving a gift, then who would call it a gift anymore... And the recipient must also have a culture of receiving the gift so as not to offend the giver while still maintaining dignity and ethics. If you have contributed to the person, then accept it and only accept it within cultural and safe limits." According to him, Tet gifts are not material things but a signal that people think of each other during Tet. And thinking of each other is culture."  Before becoming an official, Mr. Le Doan Hop was a soldier. He went through life and death with 516 comrades in a battalion, and at the end of the war, 51 people were still in the army to enter the Saigon military administration. "I am just a grain of rice on a sieve, living is thanks to luck. Therefore, I dare to affirm that during my years as a leader from the local to the central level, no one criticized me as a 'greedy person'. Because compared to my comrades, I was too profitable."

Before becoming an official, Mr. Le Doan Hop was a soldier. He went through life and death with 516 comrades in a battalion, and at the end of the war, 51 people were still in the army to enter the Saigon military administration. "I am just a grain of rice on a sieve, living is thanks to luck. Therefore, I dare to affirm that during my years as a leader from the local to the central level, no one criticized me as a 'greedy person'. Because compared to my comrades, I was too profitable."  One of his comrades at that time was the one who “gave” him a special Tet gift that he still remembers clearly. “I had a friend who fought and died together in the same unit. After the war, he returned to his hometown, his family situation was very difficult. He had a daughter who studied at university in the field of archives, but after 3 years of graduation she could not find a job. At that time, in the 2000s, I was the Chairman of the People's Committee of Nghe An province. One day, my friend and his wife and their daughter rode their bicycles to my house to ask for a favor. The wife said: “Every time my husband saw Mr. Hop on TV, he bragged that ‘Mr. Hop used to be in the same unit as you’. But the wife replied: “You always brag about knowing Mr. Hop but you don’t dare to ask him to find a job for your child.” After listening to his wife for a long time, my friend finally agreed to come to my house to present his wishes.” Mr. Hop further explained that when he was the leader of the People's Committee of Nghe An province, he realized that the capacity of commune cadres was very weak, while bachelors had no jobs. He discussed with the Standing Committee to come up with a very drastic policy: All students who graduated from regular universities with good grades or higher and did not have jobs were invited to submit their applications to the Provincial Personnel Organization Committee. After that, the province would arrange at least one person for each commune, implementing the policy of the province paying the salary, the district managing, and the commune using. "No educated person would have to go looking for a job" - he said. Returning to the story of the comrade asking for a job for his daughter, Mr. Hop immediately wrote a letter to the commune chairman asking for a job in the locality for his daughter. "Because her family is poor, she has no place to live in Vinh, so working in her hometown is the best." "I think that is a very normal help in my position to a comrade - someone who was willing to sacrifice his life to protect the Fatherland." “But the most touching was that Tet holiday,” he continued. “The couple, their daughter and her boyfriend rode two bicycles. The daughter sat behind her boyfriend, holding a case of beer, to my house to thank him. The wife said a few words that moved me to tears: “Mr. Hop, my children and I will never forget your kindness. Do you know, the first month I received my salary, I held the money my daughter brought home to give to my mother and cried.” “The Tet gift was just a case of beer, but it was more precious than gold. That was a Tet gift that I cherished and was proud to receive. I was happy to receive the gift, and the giver was also happy, because it was affection and culture.”

One of his comrades at that time was the one who “gave” him a special Tet gift that he still remembers clearly. “I had a friend who fought and died together in the same unit. After the war, he returned to his hometown, his family situation was very difficult. He had a daughter who studied at university in the field of archives, but after 3 years of graduation she could not find a job. At that time, in the 2000s, I was the Chairman of the People's Committee of Nghe An province. One day, my friend and his wife and their daughter rode their bicycles to my house to ask for a favor. The wife said: “Every time my husband saw Mr. Hop on TV, he bragged that ‘Mr. Hop used to be in the same unit as you’. But the wife replied: “You always brag about knowing Mr. Hop but you don’t dare to ask him to find a job for your child.” After listening to his wife for a long time, my friend finally agreed to come to my house to present his wishes.” Mr. Hop further explained that when he was the leader of the People's Committee of Nghe An province, he realized that the capacity of commune cadres was very weak, while bachelors had no jobs. He discussed with the Standing Committee to come up with a very drastic policy: All students who graduated from regular universities with good grades or higher and did not have jobs were invited to submit their applications to the Provincial Personnel Organization Committee. After that, the province would arrange at least one person for each commune, implementing the policy of the province paying the salary, the district managing, and the commune using. "No educated person would have to go looking for a job" - he said. Returning to the story of the comrade asking for a job for his daughter, Mr. Hop immediately wrote a letter to the commune chairman asking for a job in the locality for his daughter. "Because her family is poor, she has no place to live in Vinh, so working in her hometown is the best." "I think that is a very normal help in my position to a comrade - someone who was willing to sacrifice his life to protect the Fatherland." “But the most touching was that Tet holiday,” he continued. “The couple, their daughter and her boyfriend rode two bicycles. The daughter sat behind her boyfriend, holding a case of beer, to my house to thank him. The wife said a few words that moved me to tears: “Mr. Hop, my children and I will never forget your kindness. Do you know, the first month I received my salary, I held the money my daughter brought home to give to my mother and cried.” “The Tet gift was just a case of beer, but it was more precious than gold. That was a Tet gift that I cherished and was proud to receive. I was happy to receive the gift, and the giver was also happy, because it was affection and culture.”

Article: Nguyen Thao

Photo: Pham Hai, Character provided

Design: Nguyen Ngoc

Vietnamnet.vn

Source link

![[Photo] Closing of the 13th Conference of the 13th Party Central Committee](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/08/1759893763535_ndo_br_a3-bnd-2504-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)