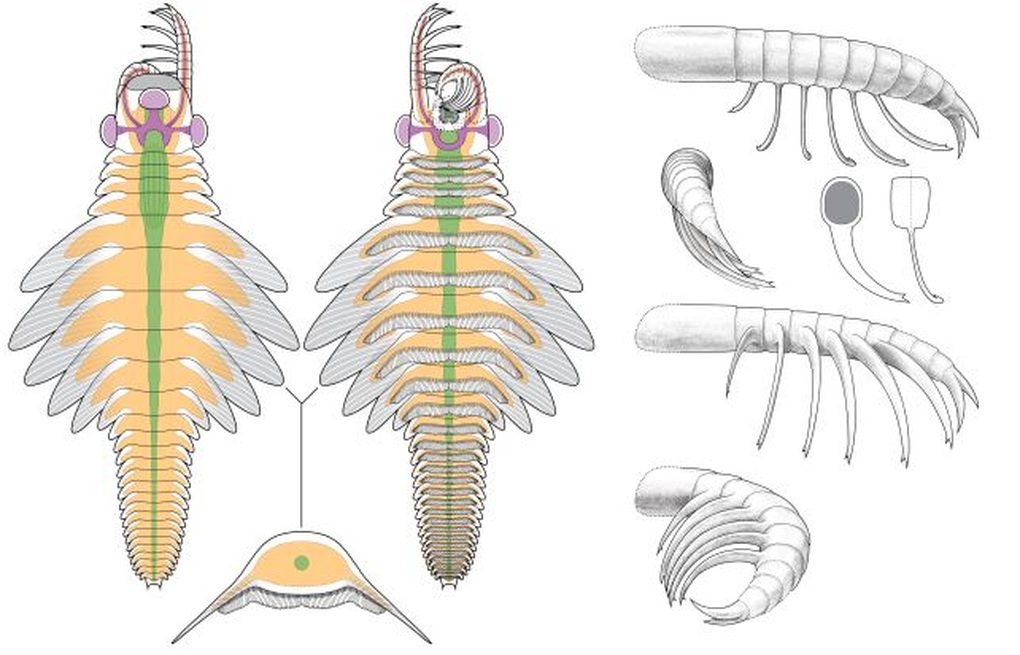

The creature, named Mosura fentoni by scientists , was an extinct radiodont arthropod. It had three eyes, used barbed claws to grab prey, fed with a round, toothed mouth, swam with fins along its sides, and had 26 body segments—the highest number ever recorded among radiodonts.

Luckily, the creature was only about the length of a human finger. In fact, most creatures of that era were quite small.

However, the complex segmented tail structure and unique anatomical features of Mosura prompted paleontologists – Joe Moysiuk (Manitoba Museum) and Jean-Bernard Caron (Royal Ontario Museum) – to devote years of intensive study.

They named the species Mosura because of its resemblance to the popular “Mothra” moth, although it is actually unrelated to modern butterflies.

Mosura had 16 main body segments with gills arranged tightly in the posterior part of the body. This is a classic example of convergent evolution, in which organisms from different groups can develop similar anatomical features as a result of adaptation to the same type of environment – as is the case with horseshoe crabs, woodlice, and many modern insects, which all have respiratory gills in the posterior part of their bodies.

The oceans of the Cambrian period, about 539 to 487 million years ago, were very different from modern marine environments. This was when the diversity of life truly began to explode, marking one of the first chapters in the history of life on Earth.

There is not much information about the Cambrian period, but the Burgess Shale geological layer in Canada is considered one of the most precious paleontological treasures. Formed about 508 million years ago, this layer of rock contains sediments from mudflows flowing across the seafloor, burying and perfectly preserving the bodies of many ancient creatures during the mudflow's deposition.

Those sediments became a Lagerstätte – a term used to describe special fossil sites that preserve fine details, soft tissue, and even internal structures – something that is rare in bioarchaeology.

In this rich ecosystem, radiodonts – an early branch of arthropods – once dominated. The most famous of these was Anomalocaris – a fearsome predator that could grow up to a meter long. While not huge by today’s standards, it was a true “monster” during the Cambrian period.

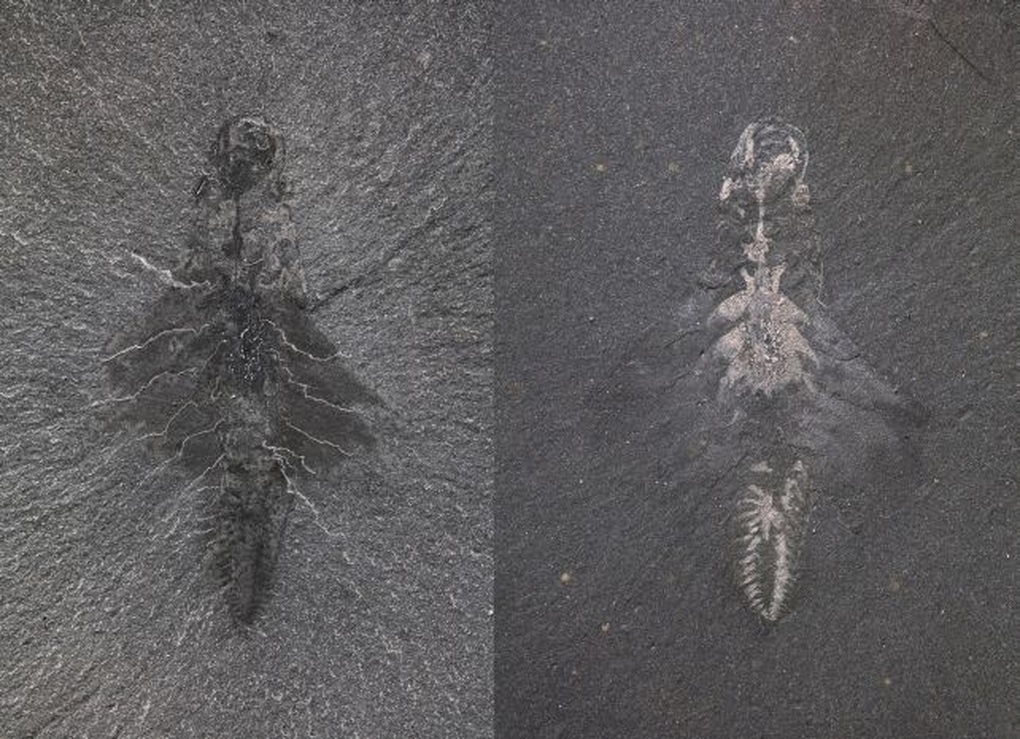

Compared to Anomalocaris, Mosura was much smaller, but possessed extremely unique anatomical features. Scientists Moysiuk and Caron studied a total of 61 Mosura fossils, thereby describing in detail the body structure, including the nervous, circulatory and digestive systems.

They found traces of nerve bundles in the eyes – indicating relatively advanced visual processing, similar to that of modern arthropods. This level of preservation is extremely rare in archaeology, especially in soft-tissue species.

Radiodonts were the first branch to branch off in the evolutionary tree of arthropods – a group that today includes insects, spiders, crustaceans and many deep-sea creatures. Studying Mosura helps scientists better understand the traits shared by their ancestors, and how modern organisms have inherited or adapted them over time.

While many features have been lost in the course of evolution, others have been preserved. Thanks to modern research methods, the excavation and interpretation of fossils like Mosura are opening up surprising answers to the origins of seemingly bizarre and inexplicable biological structures.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/quai-vat-3-mat-tung-tung-hoanh-dai-duong-cach-day-500-trieu-nam-20250527182854069.htm

![[Maritime News] More than 80% of global container shipping capacity is in the hands of MSC and major shipping alliances](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/16/6b4d586c984b4cbf8c5680352b9eaeb0)

Comment (0)