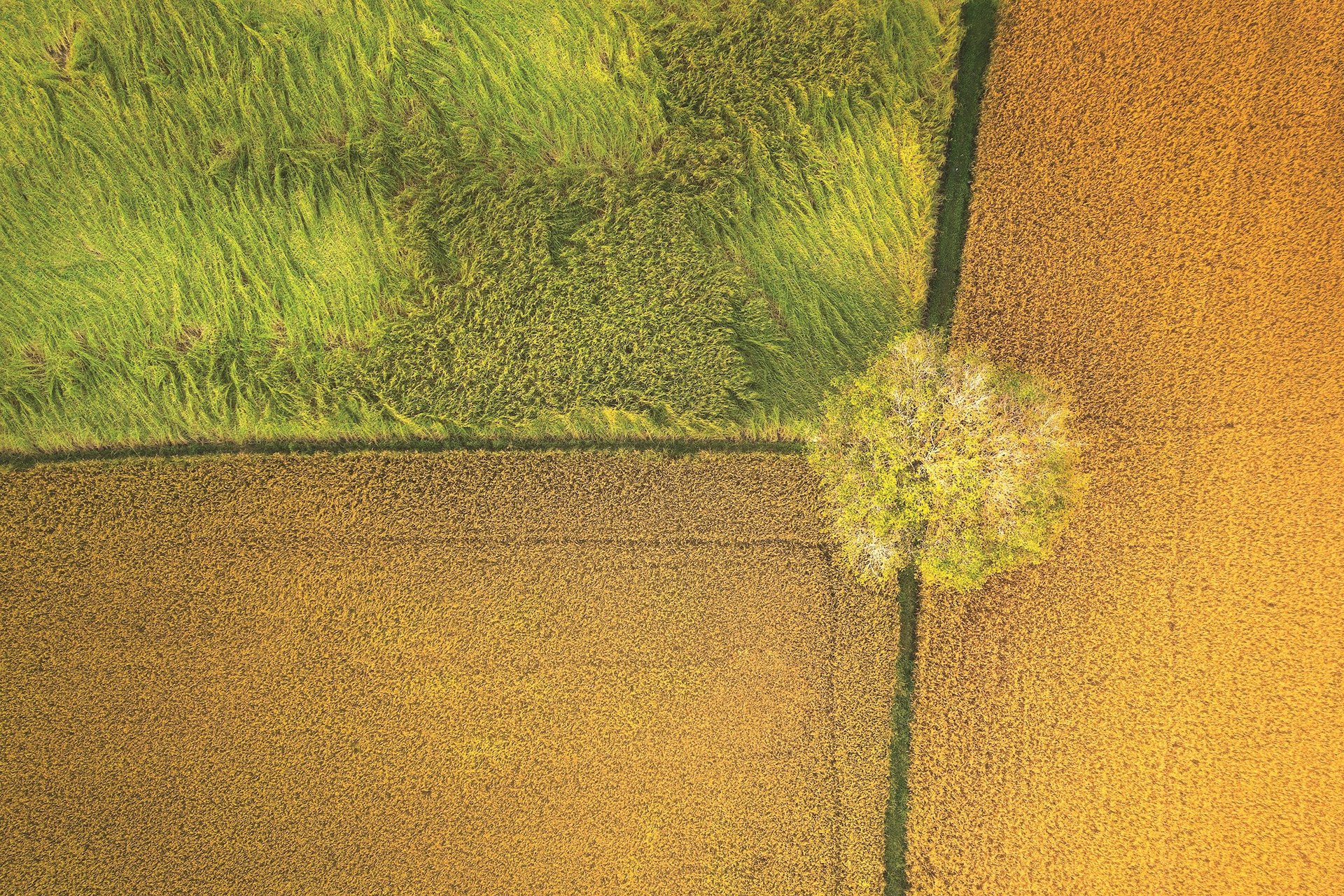

Looking at our country through the eyes of an eagle, isn't that fascinating? You nodded in agreement, saying, "Moreover, aerial photographs make us realize how small the things on this earth are, like children's toys. Even we (you trace your finger along the crowded street in the large photograph hanging in the middle of the room) are just like ants. Seeing how small we are has its advantages."

You said that for a reason.

We went to a cafe together, and my friend told me about a trip back to her old hometown earlier this year. The moment she recognized the house she used to live in through the airplane window, just over ten minutes before landing, she thought, "Where does destiny lie?"

Or perhaps it's your father's spirit right beside you, the one who prompted you to sit by the window, the one who cleared the clouds so you could see and locate the house, thanks to the Thuy Van water tower nearby, and the promontory jutting out at the river confluence. You recognize it at a glance, even though the roof tiles have changed color, a few outbuildings have been added to the back, and the trees in the garden have grown taller.

That's your scientist brain visualizing things based on proportions, but everything below is like humble toys—even the imposing water tower that you used as a landmark to find your way home when you went on a trip far away now shrinks to just over a handspan. At that moment, you fix your gaze on the house and the garden, taking in their pathetic smallness, thinking about yourself, about the battle you're about to face, about how to deliver surprise blows to secure victory.

Just minutes before, when the flight crew announced the plane would land in ten minutes, you were still reviewing your documents, estimating your lawyer's appointment, muttering persuasive arguments to yourself, imagining what your opponent would say, and how you would respond. Visiting your father's grave was a last resort, before leaving with your inheritance. Two and a half days in the place where you spent your childhood, you and your half-siblings probably couldn't even share a meal together, due to your animosity towards each other. They thought it was absurd that you hadn't been close to and cared for your father for twenty-seven years, and now you were showing up demanding a share of the inheritance—like snatching it from someone's hands.

You remember your mother's hard work when she was alive, how she single-handedly built the house from a small plot of land that only had enough space for a yard to grow portulaca, and how she saved up to buy more land and expand it into a garden. Their family couldn't just enjoy their wealth peacefully. No one was willing to give in, and when their viewpoints clashed, they had no choice but to meet in court.

But the moment you look down from above at that fortune, its insignificance makes you think that even a single cut with a knife would shatter it into tiny fragments, nothing more. Memories suddenly transport you back to the train journey your father took you to live with your grandmother, before he remarried a librarian who later bore him three more daughters.

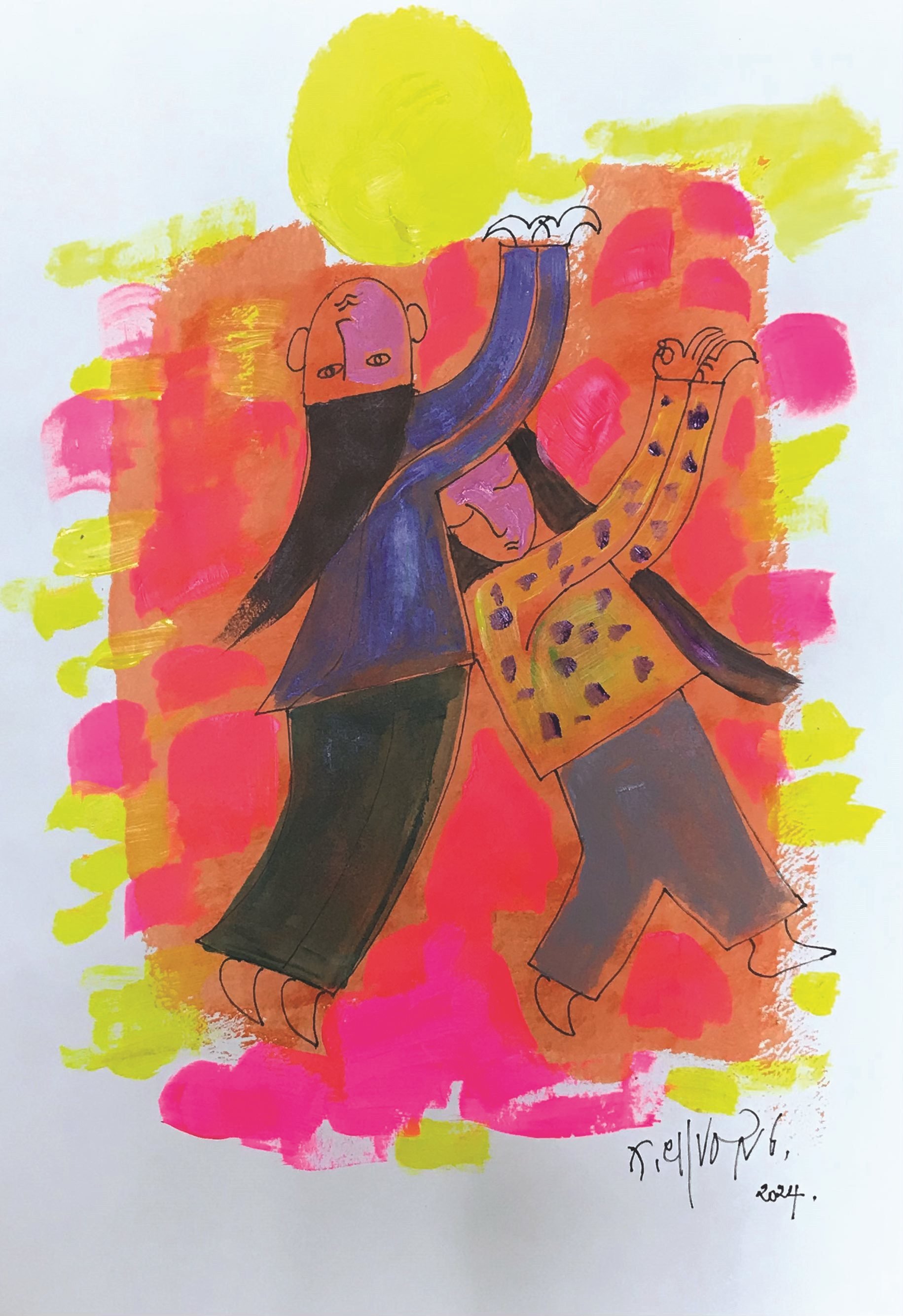

The two friends bought soft seats, speaking sparingly, their hearts filled with a jumble of emotions before their parting, knowing that after this train journey, their feelings for each other would never be the same again. They both tried to shrink back as much as possible, sinking into their seats, but couldn't avoid the chatter around them.

A rather noisy family of seven shared the same compartment, seemingly in the midst of a house move. Their belongings spilled from sacks, some bulged, others were stuffed into plastic bags. The little boy anxiously wondered if his mother hen, sent in the cargo hold, was alright. The old woman worried about her armchair, its legs already loose, fearing it would break completely after this ordeal. A young girl whimpered, unsure where her doll had gone. "Did you remember to bring the lamp for the altar?" such questions were asked abruptly along the sun-drenched train tracks.

Then, still in their booming voices, they talked about their new house, how to divide the rooms, who would sleep with whom, where to place the altar, whether the kitchen should face east or south to be auspicious according to their birth year. They lamented that their old house would likely be demolished soon, before the road leading to the new bridge was built, saying, "When they built it, I cleaned every single brick; thinking back now, it's so sad."

Around midday, the train passed a cemetery spread out on white sand. The oldest man in the family looked out and said, "Soon I'll be lying neatly in one of these graves, and so will you all. Just look." The passengers in the cabin once again turned their gaze towards the same spot, only this time there was no exclamation of wonder or admiration as when passing the flocks of sheep, the fields of fruit-laden dragon fruit, or the jagged mountain. Before the rows upon rows of graves, everyone fell silent.

“And twenty-something years later, I remember that detail most vividly, when I looked at the jumbled houses on the ground,” you said, moving your hand across the table to create a drain for the puddle of water at the bottom of your coffee cup, “suddenly a rather absurd thought popped into my head: that the houses down there were the same size and material as the graves I saw from the train when I was thirteen.”

A phone call interrupted the conversation; that day, I didn't even get to hear the ending before you had to leave. While you were waiting for the car to pick you up, I told you I was so curious about the ending—what about the inheritance, how intense the conflict was between your half-siblings, who won and who lost in that battle. You laughed, saying, "Just imagine a happy ending, but that fulfillment isn't about who gets how much."

Source

![[Image] Central Party Office summarizes work in 2025](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F18%2F1766065572073_vptw-hoi-nghi-tong-ket-89-1204-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)