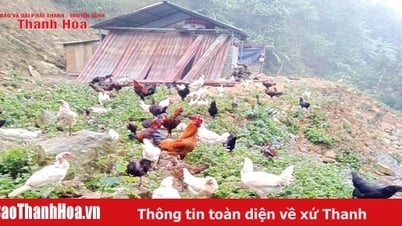

Crops are severely affected by water shortage - Photo: CAMROCKER/CANVA

In new research, scientists at the University of Oxford (UK) point out that this increasing "atmospheric thirst", also known as atmospheric evaporative demand (AED), is responsible for about 40% of the severity of drought over the past 40 years (1981 - 2022).

Think of rainfall as income and AED as spending. If income (rainfall) stays the same, we can still run a deficit if spending (AED) increases. That’s exactly what’s happening with drought: the atmosphere is demanding more water than the land can give, according to ScienceAlert on June 6.

As the Earth warms, this demand increases – drawing more moisture from soil, rivers, lakes and even trees. With thirst increasing, droughts are becoming more severe even without significant reductions in rainfall.

The AED process describes how much water the atmosphere wants from the ground. The hotter, sunnier, windier, and drier the air is, the more water it will need, even if there is no less rain.

So where rainfall hasn’t changed, we’re seeing worse droughts. The thirsty atmosphere is drying things out faster and harder, and creating more stress when water isn’t available.

The team’s new analysis shows that AEDs are not only making current droughts worse, but are also expanding the area affected by drought. Between 2018 and 2022, the global area of land affected by drought increased by 74%, and 58% of this increase was due to increases in AEDs.

The study highlights that 2022 was the most severe drought year in more than 40 years. More than 30% of the global land area experienced moderate to extreme drought conditions. In both Europe and East Africa, drought was particularly severe in 2022 – largely due to a sharp increase in AED despite a small decrease in rainfall.

In Europe alone, widespread drought has affected hydropower, crops and many cities are facing water shortages; putting unprecedented pressure on the water, agriculture and energy sectors, threatening livelihoods and economic stability.

The team's research sheds light on the dynamics of drought. They used high-quality global climate data, including temperature, wind speed, humidity and solar radiation, to measure AED - atmospheric thirst.

The team then applied rainfall and AED metrics to track where, when, and why droughts are getting worse, and calculated the severity of the increase in atmospheric thirst.

The future impacts of atmospheric thirst are significant, particularly in drought-prone regions such as west and east Africa, west and south Australia, and the southwestern United States. Without AED being included in drought monitoring and response planning, governments may underestimate the extent of the risks they face.

The study was published in the journal Nature .

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/bau-khi-quyen-trai-dat-dang-tro-nen-khat-hon-20250606102310503.htm

Comment (0)