A moment of glory after more than 40 years of waiting.

In fact, it was a moment that the scientific community had predicted ever since Pfizer and BioNTech applied messenger RNA (mRNA) technology to mass-produce vaccines, helping humanity overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. Even more noteworthy is that the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is the result of decades of tireless research and unwavering perseverance by Dr. Kariko and her colleague Drew Weissman on a technology that had previously been ignored by the rest of the world.

Therefore, it is not an exaggeration to say that the achievements of Ms. Kariko and Professor Weissman partly resemble those of the great astronomer Galileo Galilei when he discovered and firmly believed in the heliocentric theory and the fact that the Earth is spherical, despite the prevailing human belief at the time - especially the Catholic Church - that the Earth was a flat surface and the center of the universe.

Therefore, Kariko and Weissman's 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine once again reinforces that belief and the scientific spirit are always the foundation for great human discoveries, regardless of time, difficulty, and whether or not they are universally acknowledged.

Dr. Katalin Kariko (left) and Professor Drew Weissman were awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Photo: Reuters

It could be said that if the COVID-19 pandemic hadn't emerged in late 2019, mRNA technology would still be celebrated someday in human history. This is because it possesses timeless value and is essential for humanity. As we know, mRNA is not only significant in the early development of COVID vaccines, but also helps the medical community find new approaches to treating incurable diseases, including cancer and HIV.

Kariko herself admitted: “I never doubted it would work. I saw the data from animal studies and I expected it. I always wished I could live long enough to see what I was doing accepted.”

Scientific spirit and perseverance

Looking back, we see that Kariko's lifelong dedication to science is truly admirable. Immediately after graduating from university in Hungary in 1978, she began working with mRNA and would continue this mission for over 40 years afterward.

By 1985, the laboratory where Kariko worked had lost its funding and was forced to close. Quickly and decisively, she sought opportunities in the United States. Her family sold their car to buy a one-way ticket to America as a complete dedication to science.

Kariko worked at Temple University in Philadelphia for her first three years in the United States. She read scientific papers until the library closed at 11 p.m., then stayed at a friend's apartment or simply spread a sleeping bag on the office floor. At 6 a.m., she resumed her experiments and went for a run.

In 1989, Kariko got a job at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. She later collaborated with cardiologist Elliot Barnathan. They realized that mRNA could trigger cells to secrete a desired protein, helping them learn to fight off diseases and viruses—much like training a pet or an AI robot.

Kariko is obsessed with mRNA, and her colleagues say she never gets upset when things go wrong. “ The experiment never goes wrong, but your expectations do,” she often quotes Leonardo da Vinci.

But the turning point came in the late 1990s, when Kariko met immunologist Drew Weissman, who was trying to create an HIV vaccine and exploring different technologies. She introduced him to RNA—information—and then offered to create mRNA for his experiments. “I create RNA, that’s what I’m doing. I’m very good at it,” she confidently told the immunologist.

However, when Weissman conducted experiments, he found that Kariko's mRNA also triggered an inflammatory response – a swift failure. But ultimately, the tireless efforts of the two scientists paid off. Kariko and Weissman succeeded in preventing mRNA from activating the immune system. They published their findings and were granted a patent in 2005.

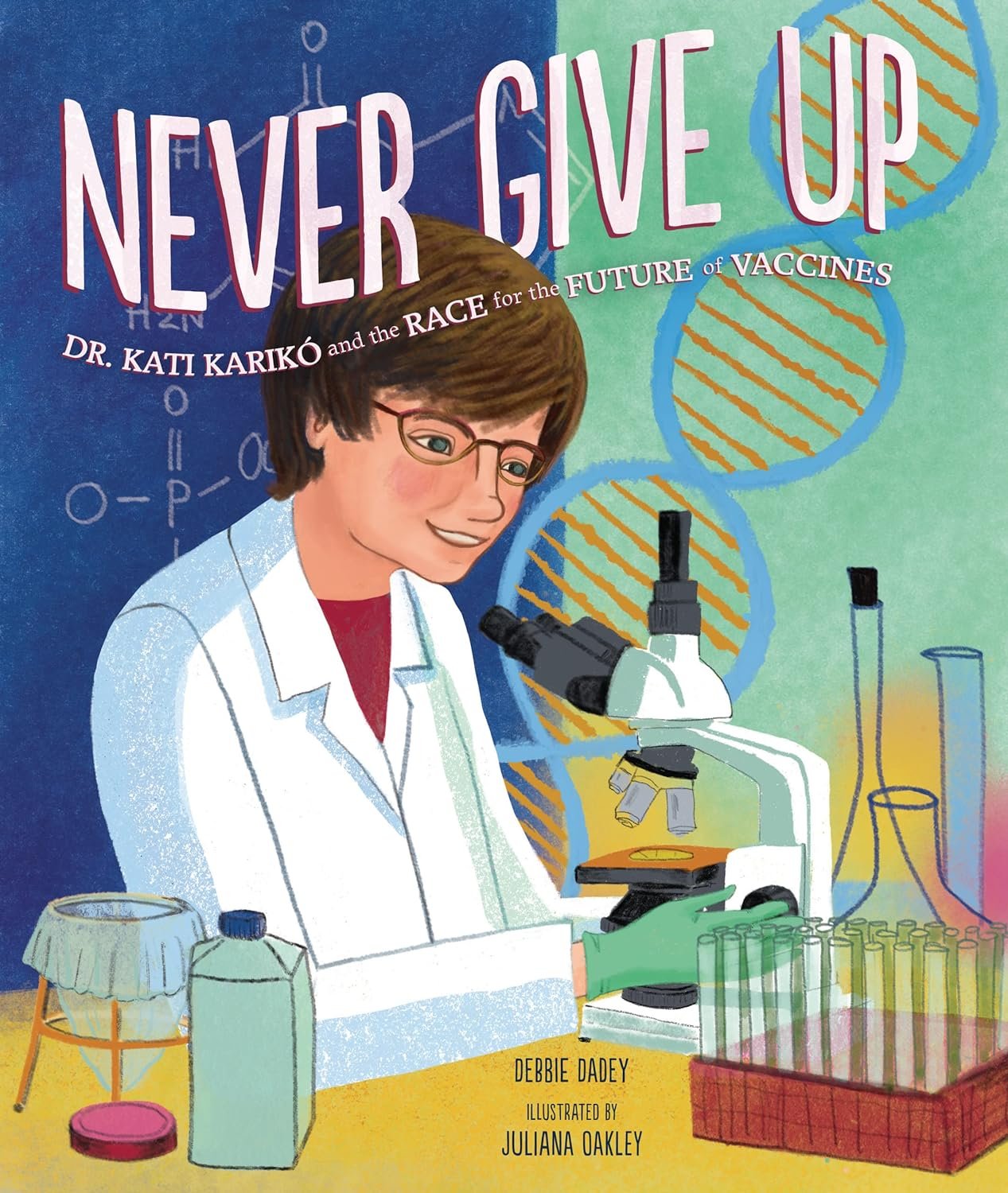

Kariko's career has been a great source of inspiration for books as well as for real life. Photo: Cover of a book about Kariko.

Never give up.

However, that was only a small and short-lived success for Kariko with mRNA. In 2013, she retired from the University of Pennsylvania without any official position. Her career seemed unsuccessful, and her lifelong work on mRNA faded into obscurity. She remained an unknown scientist at that time.

But Kariko refused to give up. She wanted to continue her research and was determined to bring mRNA into practical application. Therefore, she joined BioNTech in Germany, then an unknown startup company that had never even created an approved medical product. Every year, she would live and work in Germany for 10 months.

She recounted her difficult decision at the time: “I could have just sat in my backyard watching the grass grow. But no, I decided to go to Germany, to a biotechnology company with no website, leaving my husband and family behind. What the hell was I doing? For a whole week, I cried every night and couldn’t sleep.”

For months during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kariko would repeatedly ask her daughter, "Watch the news today. And tomorrow, as soon as you wake up, Google 'BioNTech' ." Her daughter, Susan, then a renowned skier and Olympic gold medalist, recalled, "Then one day, she abruptly hung up after a phone call and told me, 'I have to go now, goodbye!'" That was when what she had waited 40 years finally arrived. mRNA technology had been successfully applied to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

Thus, Kariko dedicated her entire career to one great moment, and it came sooner than she expected. It can be said that her journey to winning the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is a great inspiration to the whole world , as well as a reminder: Never despair and always look to the future with optimism!

Huy Hoang

Source

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man visits and works with the National Assembly Committees and the State Audit Office.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/23/1771848141941_ndo_br_bnd-6798-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)