The workload is too great while the manpower is too thin, Russian mine clearance engineers in Ukraine bet their lives with death every day.

Oleksandr Slyusar, a Ukrainian engineer with a permanent smile, spent 30 hours under Russian artillery fire in Staromaiorske, a strategic village in the Donetsk region that Kiev had just recaptured half of. A rocket exploded near Slyusar’s mine-clearing team, wounding one of his comrades.

Slyusar, 38, took his comrade to hospital in the city of Zaporizhzhia, before returning to a secret base near the front line, where the sound of Russian machine guns could be heard. He was preparing to alert an assault unit of the dangers lurking in the Russian minefields ahead.

Slyusar had been suffering from severe back pain for weeks, but the 128th brigade commander could not give him enough time for treatment.

"On paper, my brigade has 30 engineers, but in reality there are only 13. The number on duty right now is 5. I have to inject myself with painkillers every day. There are two mistakes that an engineer often makes: stepping on a mine and becoming a engineer," he said.

Ukrainian soldiers are clearing anti-tank mines. Photo: Washington Post

Ukraine is the most mined country in the world . According to the Slovakia-based research organization GLOBSEC, 173,529 square kilometers of Ukrainian land are contaminated with mines. Countless mines were planted by hand or launched by machine into fields and forests along the front line.

"In some frontline areas, there are up to five mines per square meter," said Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov.

There are mines with cute names like "butterfly mines" that are launched from mortars, helicopters or bombers, embedded in the ground and ready to explode when stepped on.

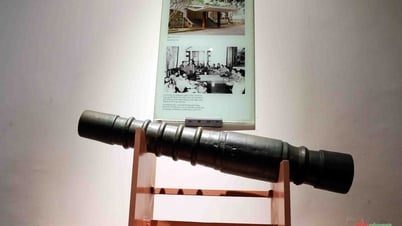

PMN mines have such a large explosive charge that they can cause a soldier to have to amputate a leg, instead of just a foot. MON-50 and MON-90 are mines that, when exploded, shoot sharp steel fragments within a radius of 90 meters.

The mines that Ukrainian soldiers fear most are the POM-2 and POM-3. They are deployed by rockets and then parachuted to the ground, with a launch mechanism ready to activate when a seismic sensor detects approaching footsteps. When activated, the mine soars to chest height and explodes, releasing about 1,850 fragments with a lethal range of 16 meters, capable of disabling an entire concentrated squad.

"You can't dismantle them and you can't survive if you get close to them. All you can do is destroy them by shooting them from a distance with an AK," Slyusar said.

Ukrainian sappers typically approach the minefields at night and begin work just before dawn, hoping to avoid Russian artillery fire. They work in four-hour shifts, during which time they can clear an area 60 centimeters wide and 100 meters long.

They crawled on the ground, using 60cm metal rods to probe the ground and using detonators to destroy anything they found. When spotted by enemy troops, they would throw smoke bombs to quickly retreat. It is not surprising that the soldiers clearing mines to clear the way for the army may not return from the mission.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense does not disclose the exact number of sappers it has. In May, it said there were about 6,000 sappers on active duty, but that number is probably much lower.

Ukraine has called on the West to provide more mine-clearing equipment. The Ukrainian Defense Ministry also recently announced that it would build its own mine-clearing equipment to clear minefields.

Slyusar said that the protective gear and mine-clearing vehicles that the West had provided were of little use on the front lines. “The machines would be hit by Russian artillery, and I couldn’t wear heavy protective gear in the woods,” he said.

The 13 men in Slyusar's unit had only night-vision goggles and "spider boots" that could protect their feet from being injured if a mine exploded. Two of Slyusar's colleagues, Kostyantyn, 38, and Andriy, 39, both lost their feet in the past week. But Slyusar said that "people are the most important factor," not equipment.

Russia's supply of mines seems endless. "They are everywhere. I can't see where it ends," said Slyusar, who has attended training courses in the US, UK and Canada.

Self-inflicted wounds pose a major challenge for surgeons. Serhiy Ryzhenko, director of the Mechnikov hospital in Dnipro, said doctors there had treated 21,000 soldiers since the conflict began. After artillery fire, landmines are the biggest killer.

"Every day Mechnikov hospital receives 50-100 people with very serious injuries. Of the 21,000 soldiers we receive, about 2,000 have lost limbs," he said.

A Russian POM-3 mine in eastern Ukraine. Photo: Telegraph

The minefields are not only a major obstacle to Ukraine's counterattack, but could also have lasting effects on the country.

The Ukrainian army has detailed maps of where they have laid mines. “Since this is our land, we have to take care of it,” said Yuri Sak, an adviser to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, adding that Russia would be unlikely to share such documents after the war even if it had them.

Pete Smith, Ukraine program manager at the demining NGO Halo, said the level of landmine contamination in Ukraine is unprecedented in modern history. The NGO currently has 900 deminers in Ukraine, mostly local, and expects that number to rise to 1,200 by the end of the year.

“If you wanted to clear all the mines in Ukraine in 10 years, you would need at least 10,000 people,” he said, based on the number of mines laid in Ukraine so far.

Thanh Tam (According to Guardian )

Source link

Comment (0)