The pay gap is a motivator

When Mana Hayashi moved to Australia last October, she knew it was going to be an adventure. But what surprised the Japanese woman was how much money she could make.

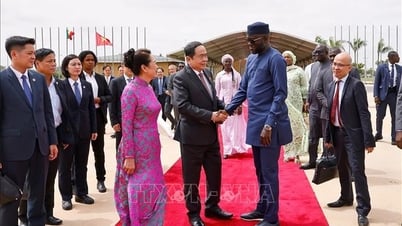

Mana Hayashi prepares sashimi at a restaurant in Melbourne, Australia, where she earns a much higher salary than she did as a nutritionist in Japan. Photo: WSJ

Hayashi, 26, landed part-time jobs at a Japanese bar, a sushi restaurant and a cafe, and was soon earning about $2,800 a month — double what she earned as a nutritionist at a hospital in Japan.

“In my experience, I feel that wages for basic workers in Japan are very low,” said Hayashi, who has worked at the hospital for about two years but has not received a significant pay rise, which is normal in a country where wages have remained virtually unchanged for three decades.

Japan has long attracted workers from developing countries in search of higher wages. But surprisingly, the yen's fall to a three-decade low and economic stagnation mean that more and more young Japanese feel it would be profitable to go in the opposite direction.

Even after the planned increase in October, Tokyo’s minimum wage will be equivalent to just $7.65 an hour, compared with $15 in New York. Median household income in Japan in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, was about $29,000 at current exchange rates, compared with $70,784 in the U.S. that year, according to government statistics in both countries.

The typical Asian-American household in the US earns more than $100,000 – more than three times what a typical Japanese family earns.

With inflation running at around 3%, Japan's price-adjusted wages have fallen year-on-year for 15 straight months through June. In the US, inflation-adjusted average hourly wages rose 1.1% in July from a year earlier.

The "reverse flow" wave

It is no wonder that more and more young Japanese people are asking whether they can make money working abroad?

Re-abroad, a Tokyo-based company that helps people study and work abroad, said the number of consultation requests in July more than tripled from a year earlier.

The number of Japanese arriving in Australia on working holiday visas, which provide temporary work permits for young people, nearly tripled to 14,398 in the year to June 30, according to Australian Government data.

Job search site Indeed says it is seeing more Japanese looking for work overseas. Indeed economist Yusuke Aoki says the trend could continue because Japanese companies, which traditionally prefer to hire new graduates, are now more open to job-hoppers. That means young Japanese feel more comfortable going abroad for a few years.

Stagnant wages are also a problem for Japan in attracting workers. With a shrinking population, Tokyo wants more workers from places like Southeast and South Asia, but it is losing competitiveness with countries like South Korea, which are also looking for foreign workers.

Wages have remained virtually unchanged in Japan for the past three decades. Photo: Bloomberg

Hayashi, a Japanese worker in Melbourne, said she had dreamed of living overseas but felt she didn’t have enough money. After hearing from a friend that she could earn more money in Australia, she decided to take the plunge.

“After less than a year, my Australian bank account started to exceed my Japanese bank account,” Hayashi told the Wall Street Journal, adding that she was saving nearly half her income so she could study childcare in Australia and stay there if she could get a long-term visa.

Hayashi recently cut back on two part-time jobs to focus more on her studies, but she said she still earns more than she did in Japan.

Makoto Nachi, 24, got a job after graduating from university selling circuit breakers and converters at a Japanese electronics company. Last year he decided to move to Australia, partly because he had always wanted to try living abroad and because he heard he could make a lot of money.

Working at a teriyaki restaurant, he said he doubled his income and saved more than $10,000 when his Australian visa expired.

In the age of remote work, another option for some is to earn dollars while still in Japan. Aiko Haruka, a 42-year-old woman in Osaka, quit her job at a Japanese foreign bank branch because she wanted to be home more often with her two young daughters.

Speaking to a Wall Street Journal reporter, she said she had received contracts to work for American technology companies, including helping with search engines and voice recognition.

Thanks to her salary in US dollars, she earned more than she did in her full-time office job at a Japanese company. “I can only assume that the Japanese economy will weaken. I want to diversify my risk by earning in different currencies,” said Aiko Haruka.

Quang Anh

Source

![[Photo] Many dykes in Bac Ninh were eroded after the circulation of storm No. 11](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/15/1760537802647_1-7384-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Conference of the Government Party Committee Standing Committee and the National Assembly Party Committee Standing Committee on the 10th Session, 15th National Assembly](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/15/1760543205375_dsc-7128-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam attends the 18th Hanoi Party Congress, term 2025-2030](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/16/1760581023342_cover-0367-jpg.webp)

![[Video] TripAdvisor honors many famous attractions of Ninh Binh](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/16/1760574721908_vinh-danh-ninh-binh-7368-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)