According to AP, Arab countries are ready to bring Syrian President Bashar al-Assad out of isolation in the hope that he will stop the trafficking and transportation of captagon - a synthetic drug containing amphetamine stimulant - out of Syria.

The vast majority of the world's Captagon is produced in Syria, while only a small amount comes from neighboring Lebanon. The United States, Britain and the European Union have accused Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, his family and allies of facilitating the production and trafficking of the pill-like drug. They say it has provided his regime with a huge financial lifeline at a time when the Syrian economy is collapsing.

The Syrian government has denied the allegations. Syrian MP Abboud al-Shawakh denied that his country profits from the drug trade and said the government was trying to crack down on it. “Our country is used as a transit route in the region because there are border crossings that are beyond the control of the government,” al-Shawakh said. He also alleged that only armed opposition groups were involved in handling captagon. Many observers have also suggested that opposition groups in Syria are involved in the drug trade.

Syria’s neighbors are the largest and most lucrative market for captagon traffickers. Hundreds of millions of captagon pills have been smuggled into Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries over the years. As Arab countries slowly repair their relationship with Syria, one of the main topics of discussion is the illicit drug industry that has flourished during the conflict there. For them, stopping the captagon trade is a top priority in negotiations with Syria to end its political isolation.

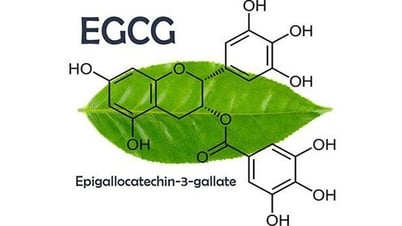

|

Captagon pills seized in the suburbs of Damascus, Syria. Photo: AP |

In early May, Syria was readmitted to the Arab League, which had suspended Syria after the conflict broke out in the country in 2011. Also in May, al-Assad was warmly welcomed at the Arab League summit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. “Al-Assad has made sure that he stops the support and protection of drug trafficking networks,” Saud Al-Sharafat, a former Jordanian intelligence official, told the AP. “For example, he facilitated the handling of drug lord Merhi al-Ramthan.”

Airstrikes in southern Syria in early May reduced the home of notorious drug lord al-Ramthan to rubble. Another airstrike destroyed a suspected captagon factory outside the southwestern Syrian city of Daraa, near the border with Jordan. The strikes came a day after the Arab League formally readmitted Syria. Syrian media recently reported that police had broken up a captagon trafficking ring in Aleppo and found 1 million pills hidden in a pickup truck.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad may hope that by cracking down on the drug trade, he can raise money to rebuild his country, further integrate into the region and even press for an end to Western sanctions, analysts say. Arab states will not be able to pump money directly into the al-Assad regime because of sanctions, said Karam Shaar, a senior fellow at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, a Washington-based nonprofit think tank. But they could channel money through UN-led projects in government-held areas to help al-Assad fight the captagon trade. A Saudi official said that anything Riyadh could provide to Syria would cost less than the damage captagon has done to Saudi youth.

The normalization of relations between Arab states and the “red carpet” treatment of President al-Assad has the United States and other Western governments concerned that it will undermine efforts to push al-Assad to make concessions to end the long-running civil war in Syria. They want al-Assad to adhere to the peace process outlined in UN Security Council Resolution 2254 (2015), which calls on President al-Assad’s government to negotiate with the opposition, rewrite the constitution and hold UN-supervised elections.

LAM ANH

Source

![[Maritime News] More than 80% of global container shipping capacity is in the hands of MSC and major shipping alliances](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/16/6b4d586c984b4cbf8c5680352b9eaeb0)

Comment (0)