|

| Dr. Nguyen Si Dung believes that reorganizing the country is essential for the nation to move into the future. |

In a powerful and symbolic speech, General Secretary To Lam affirmed: "We must reorganize the country to make it more streamlined and efficient." This is not merely a directive on administrative reform, but a declaration of reform of historical significance. Because "the country" here is not just a geographical map, but an entire system of power organizations from the central to local levels. If it is not reorganized to be more streamlined, transparent, and effective, the nation will struggle to thrive in the era of global competition.

Comprehensive and radical reform

Firstly, streamline the central government apparatus: Fewer agencies, higher efficiency. A modern national administrative system cannot have too many agencies with overlapping functions, as this wastes resources and reduces operational efficiency. Therefore, merging ministries with similar functions, such as Finance and Planning and Investment, Transport and Construction, and Natural Resources and Environment and Agriculture , is not only logical but also necessary.

At the central level, streamlining the administrative apparatus is not just about reducing the number of ministries, but also about redesigning their operational and strategic functions. A clear distinction must be made between agencies responsible for long-term strategic policy planning and those responsible for day-to-day administrative implementation. This will create a distinct two-tiered system: a thinking mind and an acting arm, without overlapping or overlapping.

Secondly, local reforms: Large scale – Small apparatus. For the first time in nearly a century, Vietnam has bravely addressed the issue of merging provinces, abolishing the district level, and building a two-tiered government model. For a long time, the three-tiered administrative model (province – district – commune) has been cumbersome, inefficient, and prone to bureaucratic hurdles. The shift to a two-tiered government model (province and commune/ward) aims to reduce intermediate levels and shorten the gap between the State and the people.

District-level administrations, which were previously merely administrative bridges, are becoming a bottleneck. Eliminating this intermediate level would not only save thousands of personnel but also represent a leap forward in thinking about modernizing the state apparatus.

The grand philosophies of "reorganizing the country"

Firstly, the closer the government is to the people, the more effective it is. At the heart of any model of power organization must be the people – the supreme subject of public power. The philosophy of "being close to the people is effective" stems from a fundamental truth in modern public administration: all public power must directly serve the public interest, not merely preserve the power structure.

The two-tiered local government model – province and commune/ward – helps shorten the distance between the administrative center and policy beneficiaries. When the commune level is given more power, clearer budgets, and a stronger organization, they will handle work closer to the people, more effectively, and in accordance with the actual living conditions of the people. Issues such as issuing documents, handling complaints, business registration, and construction permits will no longer have to go through the "intermediate station" at the district level, thereby reducing time, costs, and administrative conflicts.

Furthermore, when power is closer to the people, the pressure from social oversight is also stronger. Local officials cannot easily commit wrongdoing because the people are right there, seeing and knowing clearly. This is precisely the method of preventing corruption and negative practices at their root through transparency, accountability, and public pressure.

Secondly, reduce hierarchical levels and increase the effectiveness and speed of power. One of the chronic ailments of the administrative system is the intermediate level, where power is dispersed, overlapping, and often leads to stagnation. For many years, the district level has existed as a "transit station," lacking sufficient power to make decisions and not close enough to the people to serve them effectively, yet it is a point of origin for bureaucratic procedures, delays, and the "request-and-grant" system.

By reducing these hierarchical levels, power is redesigned to be more linear, seamless, and clear. Decisions no longer go through multiple layers of approval; responsibility is no longer passed back and forth; and the policy flow becomes shorter, faster, and more precise. This not only increases the effectiveness of the system but also clarifies individual accountability, a prerequisite for controlling power.

Instead of "not yet reached" or "unclear authority," citizens and businesses will have quick access to policies, timely government responses, and, most importantly, public trust will be enhanced thanks to clarity, transparency, and consistency in public conduct.

Third, redesigning functions and freeing the system from fragmented thinking is crucial. A common mistake in reform is confusing "mergers" with "substantive reform." Mechanically consolidating entities without redesigning internal functions and processes leads to a "two-headed snake," where functions overlap, responsibilities are dispersed, and productivity declines.

Therefore, reorganizing the country is not just about streamlining the organization, but about redesigning the system according to the principle of function and output. Each agency must have its own specific tasks and clear outputs, without encroaching on each other. Only then will each department truly function as a link in the overall system, instead of working while waiting, managing while avoiding responsibility.

This represents a significant shift from the traditional administrative model to a modern governance model, where power is delegated along with clear responsibilities, and organizations operate according to tasks rather than the old "power map."

Fourth, national strength must come from a lean, powerful, and intelligent system. In the modern world , a powerful nation cannot survive within a cumbersome and conservative system. As technology and globalization shorten distances, even a delayed decision can cause a country to miss opportunities.

Vietnam cannot enter the era of national strength in 2045 with an administrative "framework" designed in the last century. It must be restructured, streamlined, and optimized. This will not only involve reducing staff but also rebuilding the entire national operating system – where technology, data, people, and processes are efficiently interconnected.

Furthermore, "reorganizing the country" is also a starting point for a digital governance system, a digital government, and a digital society. An intelligent, interconnected, and responsive system will be the foundation for Vietnam to not only catch up, but also lead in new fields such as artificial intelligence, Industry 4.0, green economy, and innovation.

|

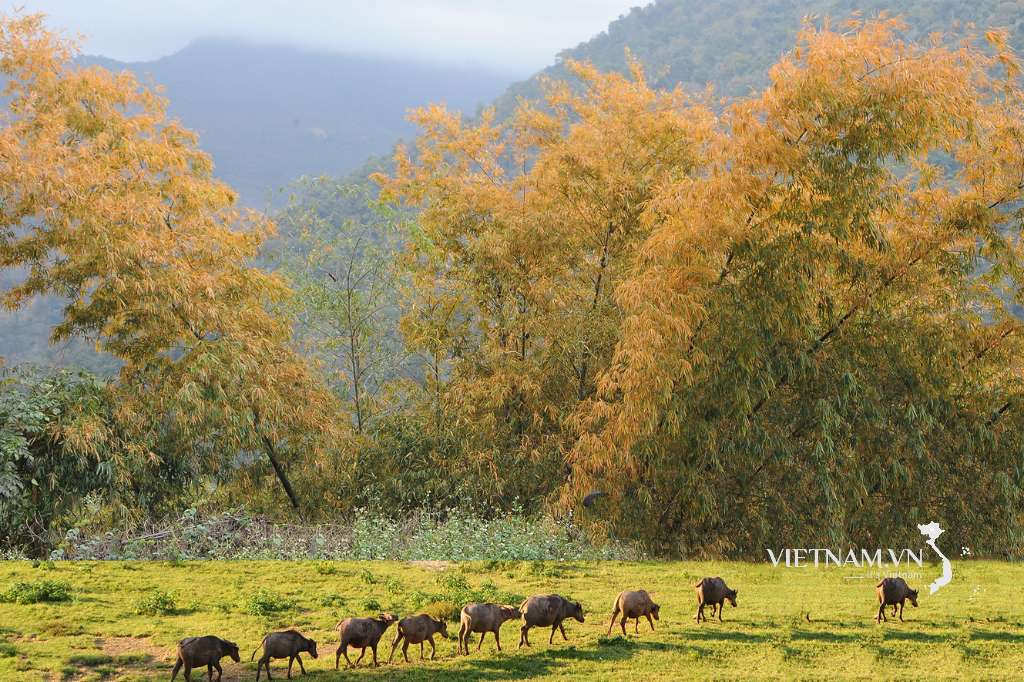

| The two-tiered local government model – provincial and commune levels – helps shorten the distance between the administrative center and policy beneficiaries. (Source: VGP) |

The challenge is significant, but it's a must-do task.

No major reform is easy, and a systemic "reorganization" will inevitably face numerous obstacles. First and foremost is the localistic mentality: Each province, district, and commune is tied to a history and identity, making it difficult to relinquish local names or authority. In many places, administrative boundaries are seen not only as administrative lines but also as symbols of honor and "local sovereignty." Therefore, merging provinces and communes is not simply a technical matter; it touches upon community sentiment, a sensitive issue that is difficult to resolve without empathetic and reasonable dialogue.

This is accompanied by concerns about personal interests and staff positions – a common obstacle in any streamlining of the organizational structure. When organizations merge, administrative levels are reduced, or departments are consolidated, personnel transfers and reassignments are inevitable, and some positions may even be cut. While the goal is to improve governance efficiency, in reality, the direct impact on people's rights is always the biggest obstacle to internal consensus.

Furthermore, a structural obstacle is the lack of consistency within the current legal framework. Many laws related to the organization of the state apparatus, local government organization, budget, decentralization, and delegation of power are still operating under the traditional three-tiered model. Without timely amendments, additions, and unification of the system, reforms could easily fall into a situation where "orders from above are ignored below," or "the top opens the way, but there are no vehicles to run on below." In such cases, major policies are easily undermined by inadequacies in the law and its implementation.

But difficulties are not a reason to delay, but rather a reason to act more decisively. No matter how great these obstacles may be, they cannot be a valid reason to retain a cumbersome, overlapping, and inefficient system. On the contrary, these very difficulties highlight the importance and urgency of reform.

Reorganizing the nation to expand its reach to the wider world.

"Rearranging the country" is not just about reorganizing the administrative map. It is an act demonstrating wisdom, courage, and the aspiration to lead the nation into a new era – where each territorial unit is not merely a geographical boundary, but also an optimal design for development. Therefore, despite the challenges, this is a task that cannot be avoided and must be accomplished.

Vietnamese history has witnessed many administrative reforms, but most were technical or half-hearted. This time, the "reorganization of the country" is a comprehensive institutional revolution, encompassing the redesign of organizational models, functions, and powers, as well as the rebuilding of data infrastructure, resource allocation, and the redesign of relationships between different levels of government.

It requires: Progressive reform thinking, breaking free from old administrative patterns; Political courage to confront local and conservative reactions; The capacity to organize and implement, from institutionalization through legislation to concrete implementation; and the trust of the people, because only when the people are united can reform succeed.

Vietnam is standing at a historical crossroads. To become a developed nation, it cannot carry on a cumbersome and inefficient bureaucracy. It must be streamlined, efficient, and a "reorganization of the nation" is necessary. This is not just about aesthetics, but about ensuring that the bureaucracy truly becomes a tool for development, serving the people and leading the nation into the future.

"Reorganizing the nation" is an institutional cleanup, but more fundamentally, it is a renewal of leadership thinking, a rebuilding of public trust, and the initiation of a new era of powerful development.

Source: https://baoquocte.vn/ts-nguyen-si-dung-sap-xep-lai-giang-son-de-vuon-minh-ra-bien-lon-321964.html

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the Conference on the Implementation of Tasks for 2026 of the Industry and Trade Sector](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F19%2F1766159500458_ndo_br_shared31-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)