Located on the right bank of the gentle Cai Be River, Ta Nien village, which the Khmer call Crò-tiêl, has been making mat weaving looms for generations. Not only a consumer product, Ta Nien mats are also a symbol of the combination of hard-working hands and refined folk aesthetics. Through the ups and downs of history, the craft village has persistently preserved each sedge blade and each pattern, as if preserving the cultural memory of an entire southern river region.

Traditional profession still throbbing

Mat weaving in Vietnam has a long history, associated with the founder of the profession, the first-ranking scholar Pham Don Le, from Hoi village (now Thai Binh ). After learning the technique of weaving mats from Que Lam (China), he improved the weaving frame, developed the sedge growing profession and spread it throughout the country. From there, craft villages such as Hoi and Nga Son gradually spread following the footsteps of the Vietnamese people on their journey to the South, sowing the seeds of weaving in new lands.

In Ha Tien (ancient Kien Giang ), which was once a meeting point for Vietnamese, Chinese and Khmer people, mat weaving quickly took root. According to many hypotheses, the name "Ha Tien" may have originated from the Khmer word "Kro-tiêl" (mat) combined with the word "Pem" (river mouth), as a vivid proof of the connection between this land and traditional handicrafts. Among them, Ta Nien emerged as one of the typical cradles with long stretches of natural lac gon fields, providing abundant raw materials for mat weaving.

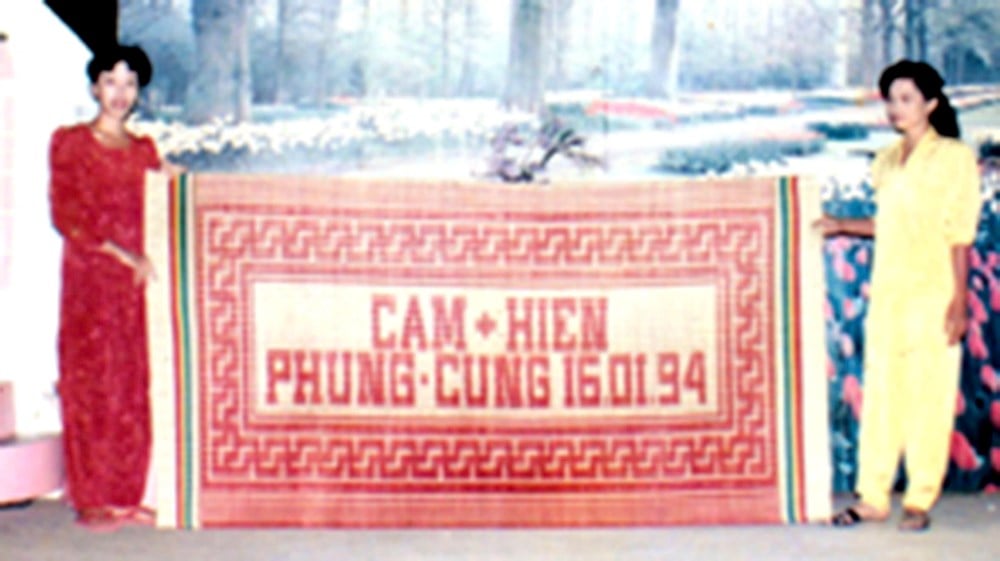

Ta Nien mats are famous for their durability, harmonious colors and delicate patterns, associated with the legend of the national hero Nguyen Trung Truc. In particular, the "Tho" character pattern woven on the mat also carries the depth of culture and indigenous spirit. Throughout the 20th century, Ta Nien mats have appeared at a series of famous fairs at home and abroad, from Hanoi , Saigon to Marseille (France), contributing to introducing Vietnamese culture to international friends. Mats named Ta Nien won a gold medal at the National Fair in 1985, and were the pride of Kien Giang during its brilliant development period from the 18th century to the end of the 20th century.

However, after storm No. 5 in 1997, the mat weaving profession began to fall into a difficult period. Changing consumer tastes, a shortage of successor labor, and rural industrialization caused the craft village to gradually disappear. However, in each old loom, in the memories of the local people, the mat weaving profession is still like a smoldering flame waiting to be rekindled...

The breath of evil in every strand of grass

The main raw material of Ta Nien mat is sedge, a plant that grows naturally in coastal saltwater wetlands, belonging to the Cyperus family. The sedge stalks are 1-2 meters long, light green, with a slender stem and a crown-like fringed tip. People take advantage of this natural growth to harvest up to 3 crops per year, exploiting for 8-15 years on a field.

To make the mat durable, the craftsman must use additional “ba” fibers spun from jute bark, which act as a skeleton to support each sedge. The jute spinning wheels, sharp knives and simple wooden looms have accompanied the Ta Nien craftsmen throughout their lives, weaving countless mats for use in everything from rural markets to luxurious homes.

The mat making process begins with the splitting of the sedge. After harvesting, the sedge stalks are sorted, split in half, the core removed, polished and dried in the sun for 2-3 days. Sunlight is a vital factor, if there is not enough sunlight, the fibers will fade, break easily, reducing the quality of the mat. After drying, the sedge is dyed, each bundle of sedge is soaked in boiled colored water to absorb evenly, then dried again.

The weaving stage is the most important. The mat loom requires two people, one person swings the shuttle, threads the thread through the loom and the other person weaves, pulls the stamping bar to create a tight bond between each sedge thread. Each pair of mats usually takes 4-5 hours to weave, while the high-end mats with intricate patterns can take up to 5-7 days to complete, weigh nearly 10kg and can be used for up to 7 years without deteriorating.

Ta Nien mats are also very diverse, from the common, fast-woven mats; medium mats with uniform materials; mats made to order with meticulous attention to each stage. Based on weaving techniques, mats are divided into three main lines: Ladder mats (high-class, durable, waterproof); dyed mats (simple colors, fast weaving); printed mats (woven with white sedge, printed with patterns after completion).

Once a “fishing rod” for hundreds of households in Vinh Hoa Hiep commune, Ta Nien mats were widely consumed through traders, orders or direct sales in the region. Even before 1975, Ta Nien mats were exported to markets such as Malaysia, Japan, India, France, Germany...

Despite its former glory, Ta Nien mats today face many challenges such as scarcity of raw materials, the decline of traditional crafts, and the lack of interest from young people in continuing them. However, in old houses, the looms still make a clattering sound, and somewhere there are still workers quietly keeping the flame of a heritage alive.

Preserving a craft village

Not only is Ta Nien mats proud of their economic value, they are also famous for their tolerance, from illiterate people, manual laborers to even the disabled. It is a place of refuge, a place to preserve family and village traditions.

However, life has changed. The sedge fields of the past have gradually disappeared. Consumer tastes have also shifted to more convenient products such as rubber mattresses, bamboo mats, and plastic mats. The best quality, patterned, high-tech mats are almost no longer ordered. The remaining craftsmen now only weave mats during the off-season to earn extra income. The entire craft village is quietly struggling to survive in the situation of “taking labor for profit”, with production at a moderate level.

The craft is easy to learn but not easy to maintain. Although the mat weaving process is not too complicated, to create truly beautiful, durable, and tasteful products, the craftsman must be meticulous, creative, and passionate. Unfortunately, the craft is still passed down from family to family in a “father-to-son” manner without proper organization or attention to develop into a real craft village.

The decline of Ta Nien mats is a wake-up call for many other traditional craft villages. In the context of integration and modernization, without practical support policies, cooperative models, and systematic production-consumption linkages, the once-famous values of Ta Nien mats can easily be erased.

Preserving the craft is preserving the village! To preserve Ta Nien mats, the whole community needs to join hands, from local authorities, industry and trade, businesses to cultural organizations. There needs to be clear directions in planning for craft village development, connecting traditional handicraft products with tourism, trade and community cultural education.

Source: https://baovanhoa.vn/van-hoa/tu-tieng-ca-ben-dong-cai-be-den-chieu-lac-ta-nien-144304.html

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man holds talks with New Zealand Parliament Chairman](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/8/28/c90fcbe09a1d4a028b7623ae366b741d)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam attends the opening ceremony of the National Achievements Exhibition](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/8/28/d371751d37634474bb3d91c6f701be7f)

![[Photo] Images of the State-level preliminary rehearsal of the military parade at Ba Dinh Square](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/8/27/807e4479c81f408ca16b916ba381b667)

Comment (0)