Calvin Eng is the owner of Bonnie's, a Cantonese Chinese restaurant in New York. He has an unabashed love for monosodium glutamate, or MSG. He even has the word “MSG” tattooed on his arm. His restaurant menu also includes a special drink called the MSG Martini.

“Everything tastes better with MSG, whether it’s Western food or Cantonese food,” he told CNN. “We use MSG in drinks. We use it in desserts or savory foods. MSG is in almost every dish. Salt, sugar and MSG – I always joke that they are the trinity of Chinese cooking.

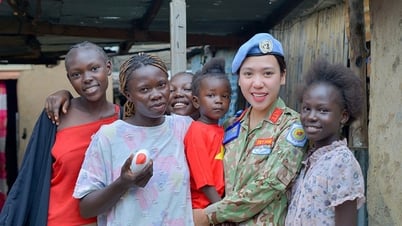

CNN said that the public admission of using MSG — a condiment that once terrified many — will not affect the success of Bonnie's. It has become one of New York's most beloved restaurants since Calvin opened it in Brooklyn in late 2021. Bonnie's has won numerous awards for best new restaurant from a variety of media outlets.

Calvin Eng himself was named one of the best new chefs of 2022 by Food and Wine Magazine. Calvin was also included in the Forbes 30 under 30 list in 2023, and this is just one of his recent achievements.

Once a "taboo" spice

Calvin Eng is among a number of celebrity chefs — including Momofuku's David Chang and Eddie Huang, the American author, chef and co-owner of Manhattan's acclaimed BaoHaus — who are rediscovering MSG and trying to shed the stigma around the centuries-old spice.

“When I was growing up, MSG was taboo,” Calvin told CNN. “My mom never used MSG, but she used chicken bouillon powder in her cooking. As a kid, I had no idea that they were actually the same thing until I grew up and learned about it.”

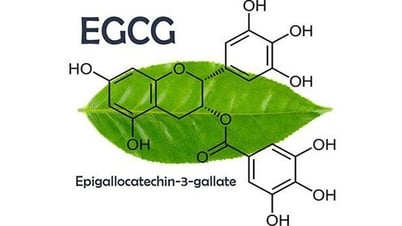

MSG has an interesting history. In 1907, Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda boiled large quantities of kombu seaweed to extract glutamate, which gives certain foods, like dashi stock, a long-lasting savory flavor. He classified the newly extracted substance as “umami” (or savory) and further refined it into MSG, which in its crystalline form can be used like salt and sugar.

A year later, businessman Saburosuke Suzuki bought part of the patent for MSG and, together with Ikeda, founded the Ajinomoto Company to produce the condiment. MSG quickly caught on, becoming a highly regarded condiment, especially among middle-class housewives in Japan.

In the following decades, MSG became famous around the world . The US military even held its first MSG symposium after World War II to discuss how to use the spice to create better battlefield rations and thereby boost soldiers' morale.

But MSG got a bad rap in 1968, when an American doctor submitted an article titled “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” to a medical journal. In the article, he described symptoms such as “numbness in the back of the neck,” “fatigue,” and “palpitations.” He suspected that MSG, along with other ingredients like cooking wine and high sodium levels, might be the culprit.

The article created a seismic shockwave, with negative repercussions against MSG spreading around the world for decades. Restaurants publicly boycotted MSG. Food and beverage advertisers begged consumers not to ask about it. Diners blamed MSG every time they felt sick after a meal.

What are the ingredients of MSG?

“A lot of people don’t realize that MSG is derived from plants,” Tia Rains, a nutrition scientist in Chicago and Ajinomoto’s vice president of customer engagement and strategic development, told CNN. “We make MSG through a fermentation process, very similar to how we brew beer or make yogurt.”

First, sugary plants – like sugar cane or corn – are fermented by bacteria to produce glutamate, an amino acid found in foods. Glutamate is also produced by our bodies and acts as a neurotransmitter.

Sodium is then added to crystallize the glutamate and become MSG, which resembles fine salt, as we see in supermarkets and kitchens today.

“I’m a scientist. I think MSG is one of the most interesting things about science,” Rains said. “We have different receptors on our tongues for different flavors. Under a microscope, the umami receptor on the tongue looks like a trapdoor. Glutamate, as an amino acid, fits perfectly into that receptor.”

So what is umami? In recent years, umami has been called the “fifth taste” – combining the familiar tastes we already know such as sweet, sour, salty and bitter. Interestingly, umami is described as having a slightly salty taste.

When glutamate enters the receptor, it creates the umami taste sensation on our tongue. If the food contains either of the two nucleotides inosinate or guanylate, glutamate can stick to the receptor for a longer period of time.

“In layman's terms, if you want to make an umami bomb, combine glutamate—the core ingredient in umami—with one of these nucleotides (inosinate and guanylate). It's like giving your brain a burst of umami,” Rains explains.

If this all sounds complicated, you’re probably already using glutamate, inosinate, and guanylate in your cooking without even realizing it. For example, carrots and onions are high in glutamate, which enhances the umami taste of beef (which is high in inosinate). Tuna (high inosinate) and kombu seaweed (high in glutamate) also work well together to create a rich umami taste. Foods like tomatoes and cheese also contain glutamate naturally.

“When someone tells me they just went to a Chinese restaurant and had difficulty breathing and chest tightness, I get concerned. I tell them to watch carefully, because MSG is not an allergen. Our bodies make glutamate, so you can’t be allergic to glutamate,” Rains said.

CNN reports that despite the negative claims made by diners about MSG, decades of scientific testing has shown no such thing as a “MSG sensitivity.” Many government agencies around the world, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have deemed MSG a safe food additive.

The Hong Kong Center for Food Safety notes that using MSG can reduce sodium intake, which is linked to health problems such as high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke.

Changing user perception

To this day, negative sentiments continue to permeate much of the discussion around MSG. But a new generation of chefs like Calvin Eng are not afraid to talk about MSG and list it on their menus. Their actions are helping to change outdated perceptions.

“I think our young customers are very aware of MSG and are not afraid to use it. We are proud to embrace and use MSG, to help erase the bad reputation it once had.”

Health concerns aside, some diners view MSG as a quick and easy way to enhance the flavor of their food. Calvin Eng disagrees. He says his restaurant's dishes are prepared the traditional way.

“We make braised dishes and broths by simmering ingredients for hours. We just add a little MSG. What we do is very different from boiling water, adding MSG and then eating that broth with noodles,” he said.

Many of Bonnie's dishes are Cantonese in origin, but with fresh, sophisticated twists. For example, the shop's char siu sandwich is inspired by two dishes: the classic McDonald's McRib and Calvin's mother's favorite black bean short ribs.

To make the dish, Calvin steams the ribs until the meat falls easily off the bone. He then marinates the deboned ribs overnight in a homemade char siu sauce, seasoned with MSG and more. When the meat is ready, it is pressed and flattened and grilled. Finally, Calvin places the grilled ribs, along with onions, pickles, and mustard, on a classic Cantonese bun from his mother’s favorite Cantonese bakery in Chinatown. It has been the most popular item on the menu since Bonnie’s opened.

He hopes that as MSG's reputation improves in the US, the controversial spice will gradually gain a more favorable view elsewhere in the world./.

Source

![[Maritime News] More than 80% of global container shipping capacity is in the hands of MSC and major shipping alliances](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/16/6b4d586c984b4cbf8c5680352b9eaeb0)

Comment (0)