Moustapha & Yu conducted a quantitative study of 35 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and found that a 1% increase in spending on research and development (R&D) can contribute to a 2.83% increase in real GDP growth, demonstrating the pivotal role of innovation in long-term economic growth.

According to World Bank statistics in 2024, in Vietnam, the ratio of R&D spending to GDP has increased from 0.3% in 2013 to 0.43% in 2021. This is a positive step forward, but still low compared to the average of developed countries (usually ranging from 2% - 4% of GDP).

Vietnam still faces many challenges such as limitations in technology adoption and mastery, lack of linkages between businesses and universities, and ineffective exploitation of global intellectual resources.

AVSE Global (Vietnam Science and Expert Organization Global) is a non-profit organization based in Paris, in collaboration with the People's Committee of Ninh Binh province to organize the Vietnam Research and Development Forum 2025 (Vietnam R&D Forum - VRDF 2025) with the theme: "Promoting Vietnam's future through strategic R&D investment".

This event is expected to be a strategic step to promote the transition to a knowledge-based economy, while enhancing endogenous innovation capacity – a key factor for sustainable development and enhancing national status.

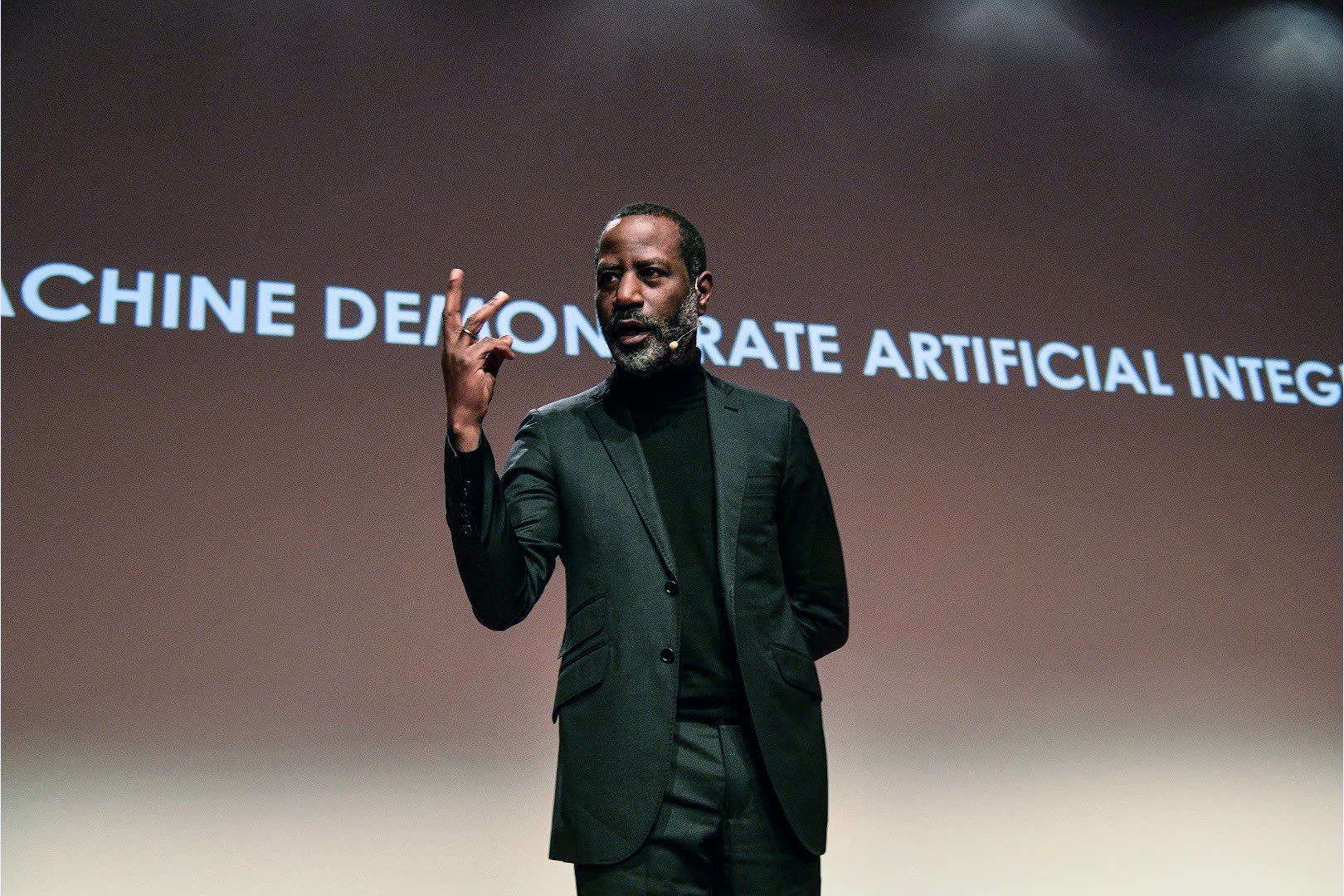

VietNamNet had an interview with Mr. Hamilton Mann about R&D strategy in Vietnam. Mr. Hamilton is an international technology expert, currently Group Vice President at Thales, where he co-leads the global digital transformation and AI program for the world's leading corporation in the fields of defense, aerospace and cybersecurity.

Who and what is R&D for?

Mr. Hamilton Mann, what are the fundamental elements to establish a long-term and sustainable connection mechanism between stakeholders in the R&D ecosystem – such as the state, enterprises, institutes/schools and the international community?

What matters is not what you intend to do with R&D, but answering the more fundamental question: Who is R&D serving and for what purpose? This is the first fundamental element: the purpose of R&D needs to be reframed – not as an intrinsic motivator, but as a connecting fulcrum.

R&D needs to be designed as a platform model – a structure that allows for value creation in multiple dimensions. Within that platform logic, the starting point of any technological R&D activity is essentially an “ideological R&D”: that is, deliberately asking why innovation is needed, and who is innovation serving?.

Each group – from government agencies, private businesses, academia to civil society – has its own priorities, constraints, and capacities. The goal is not to homogenize, but to create an environment where different contributions enhance the overall trajectory, producing results that are superior to what each could do alone.

However, will and inclusiveness are not enough. The second fundamental factor is support mechanisms. For the R&D platform model to develop, stakeholders need to overcome two main barriers: Access costs – including information, finance, infrastructure, and partners; Transaction costs – including legal, technical, cultural, and organizational barriers that hinder trust, coordination, and implementation.

These mechanisms not only provide access but also ensure stability, interoperability and accountability.

In short, two elements - common goals and systemic mechanisms - are the foundation for developing a sustainable R&D ecosystem.

From your experience in Europe and MIT, are there any typical R&D cooperation models that Vietnam can learn from to develop long-term strategic partnerships?

Both Europe and MIT provide R&D models that are not meant to be copied, but to derive principles that can be adjusted to the context, which is especially useful for countries that are building innovation ecosystems and want to assert their position in the global value chain like Vietnam.

Fraunhofer model (Germany): The Fraunhofer model stands out with its hybrid funding system: About 30% from the state budget, 70% from applied research contracts with businesses. Fraunhofer institutes are often closely linked to local industrial clusters, have a clear mission orientation, and focus on commercial-ready innovation.

The lesson for Vietnam: not in the organizational model, but in the principle - linking research capacity with the mission of serving industry, sharing ownership and risk.

EIT & KICs model (Europe): European Institutes of Innovation and Technology (EIT) and Knowledge-Innovation Communities (KICs) are European-scale public-private-academic networks around major societal challenges such as climate, health, transport, digitalisation…

This model allows for both local experimentation and system-level learning.

Vietnam can apply this logic to build regional centers of excellence, not alone but as a foundation for developing ecosystems around national missions such as digital infrastructure, smart agriculture or climate change adaptation.

MIT Industrial Liaison Program (ILP): More than just connecting businesses with faculty, ILP designs long-term strategic relationships between global businesses and the MIT innovation ecosystem, including startups, spin-offs, and applied labs.

MIT Jameel World Education Lab (J-WEL): This program partners with governments, universities, and development funds in developing countries to co-create innovation capacity, rather than simply transfer it. It is unique in its long-term commitment and focus on building institutional capacity.

Vietnam – with its penchant for investing in education and digital transformation – could well benefit from this model, in the form of multi-year capacity development programmes that aim to build rather than exploit.

Policy helps ideas mature into “investable signals”

One of the common bottlenecks in developing countries is the gap between research and the market. How do you see the role of policy in promoting the transfer and commercialization of research results in Vietnam?

The gap between research and market is often misinterpreted as a lack of technology or entrepreneurial spirit. But it is actually a design gap – a failure to align the motivation, capacity, and timing of the research ecosystem with the market ecosystem.

This is where public policy has a crucial role to play, not just in funding, but in setting the conditions for transfer to become a sustainable norm and create value.

Public policy needs to intervene at three integrated levels:

Mission framework: For example, the Catapult centres in the UK, funded by the government to undertake strategic industrial missions (advanced manufacturing, energy, cellular medicine, etc.). The policy here is not outcome-driven but goal-oriented – helping businesses understand “for whom” and “for what” they should engage in R&D.

Building a platform – reducing system friction: A prominent example is VTT in Finland, which is not only a research institute but also a neutral integrator between academia and industry. They provide shared labs, support intellectual property transfer, and project coordination – reducing access and transaction costs.

Building capacity - filling the intermediary gap: A major bottleneck in developing countries is the lack of intermediary institutions and skills that can turn research results into business models, prototypes or legal strategies. Take Israel, for example: the Israel Innovation Authority (IIA) not only funds R&D, but also invests in technology transfer offices, idea testing programs, public-private incubators, etc.

The policy here is to help ideas mature into “investable signals” – this is the key value layer that Vietnam needs to build.

In short, public policy needs to be designed as the glue between science, markets, and society, not just through funding but also through norms, shared infrastructure, incentives, and social legitimacy.

Public policy needs to create an architecture for R&D: Orientation - reducing friction - increasing capacity. Then commercialization is no longer a bottleneck, but a strategic engine for creating national value.

So that businesses are no longer “recipients”, but learning partners

In the innovation ecosystem, businesses are often “knowledge buyers”. In your opinion, how can the private sector in Vietnam participate more actively in R&D investment and exploit research results from the academic sector?

First of all, I want to question the very concept of “knowledge buyer.”

Viewing businesses as “buyers of knowledge” reflects a transactional view of innovation – where academia produces and industry consumes. But in reality, innovation does not come from the simple transfer of knowledge, but from the co-evolution of knowledge and demand.

This requires the private sector not only to absorb research, but also to proactively shape the conditions for research to be relevant, applicable, and scalable.

In Vietnam, this means making businesses the “center” of the innovation ecosystem. Not just providing funding when it is convenient, but participating from the beginning, integrating capabilities, and jointly owning the innovation path.

Model from Denmark: GTS Institute of Advanced Technology: This institute acts as an intermediary for applied R&D between universities and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Its strength is that companies, especially medium-sized ones, pool capital into technology platforms that they could not develop on their own. Businesses do not just “buy” research, but jointly identify problems, test solutions, and reduce innovation risks.

This is an effective model for Vietnamese enterprises to strategically gather applied research needs, especially in essential fields such as high-tech agriculture, logistics, green manufacturing, etc.

Model from Singapore: A*STAR's Tech Access Initiative: Here, businesses - especially small and medium-sized enterprises - have access to labs and advanced equipment at preferential prices supported by the government, along with technical advice, sample testing, training... Research is no longer a "luxury" but has become a "capacity launch pad" for businesses.

In this model, the private sector brings practical problems, product development needs, and innovation goals into the system, becoming a co-determiner of applied R&D programs, rather than passively waiting for academic results to "flow down."

They are no longer “recipients”, but learning partners, multipliers of national R&D assets, turning research infrastructure into a platform for long-term competitiveness.

The most important strategic shift lies in mindset: Developing talent, building trust and a long-term vision are just as important as intellectual property rights.

Businesses need to move beyond the “Return on Product” mindset to “Return on Participation” – which includes people, collaboration, and ecosystem factors.

When businesses become not just “knowledge buyers” but “knowledge creators,” they not only accelerate their own innovation but also elevate the entire national creative capacity.

* Part 2: R&D investment must be linked to "national mission"

Hamilton Mann is an international technology expert, bestselling author, and currently Group Vice President at Thales, where he co-leads the global digital transformation and AI program for the world's leading defense, aerospace, and cybersecurity company.

He is a lecturer at INSEAD and HEC Paris, and a PhD candidate in Artificial Intelligence at the École des Ponts – Polytechnic Institute of Paris. Hamilton is also a consultant at the Priscilla King Gray Center (MIT) and a Senior Fellow at the Retech Center (France).

In 2024, he was honored by Technology Magazine as a Top 10 Global Technology Thinker, selected to Thinkers50 Radar, and in 2025 was awarded the title of Digital & AI Leader for Humanity by Who Is Who International Awards.

Source: https://vietnamnet.vn/khi-doanh-nghiep-khong-chi-la-nguoi-mua-ma-la-nguoi-kien-tao-tri-thuc-2426559.html

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman attends the seminar "Building and operating an international financial center and recommendations for Vietnam"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/28/76393436936e457db31ec84433289f72)

Comment (0)