(CLO) Silva, the surname or given name of about 5 million Brazilians, has long been seen as a legacy of a dark chapter in the colonial era. But now, many are seeing their Silva name in new ways.

Legacy of a Dark Age

The surname of Fernando Santos da Silva - and that of his roughly 150 relatives - is a legacy of a dark chapter in Brazilian history.

Like millions of others in Latin America's most populous country, Fernando Santos da Silva inherited this legacy from his ancestors, who were enslaved, possibly because they were named after their captors.

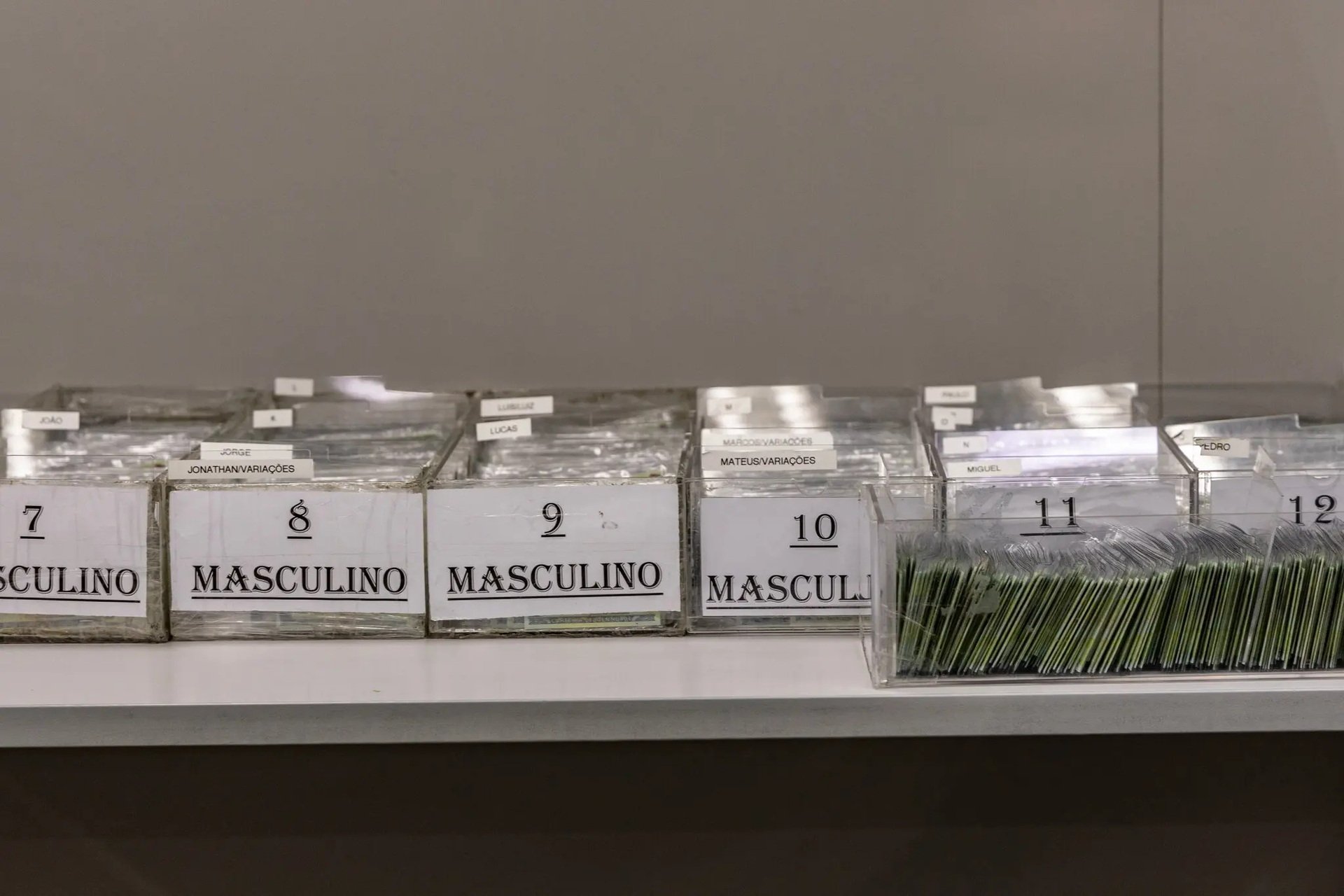

Citizenship identification cards are set to be delivered to a government facility in Rio de Janeiro in November. About 5 million Brazilians have the surname Silva. Photo: New York Times

With its painful origins, Silva has long been a source of shame even as it became the most common surname in Brazil. But today, Silva is understood in a completely different way.

“Silva is a symbol of resistance,” said Santos da Silva, 32, an antiques dealer from Rio de Janeiro. “It is a connection, both to the present and to my ancestors.”

Whenever you meet a Brazilian, chances are Silva is tucked away somewhere in a long, melodious surname. If not, they probably have a friend or relative with that name. (Most Brazilians use both their mother's and father's last names.)

Silva is found in the names of Brazil's president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and the country's most famous footballer today, Neymar da Silva Santos Júnior. It is also shared by about 5 million other Brazilians, from movie stars and Olympic medalists to teachers, drivers and cleaners.

Exactly how Silva spread across Brazil – one in 40 Brazilians have the name – is the subject of some debate. But historians agree that much of its popularity has to do with slave owners giving the name to many of their slaves, who then passed it on to future generations.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is also a Silva. Photo: Reuters

With colonial roots, the name has for decades been synonymous with poverty and oppression in a predominantly black country where slavery was only abolished in 1888 and deep racial and economic inequality persists.

In Brazilian popular culture, the plight of Silvas has long been widely represented, for example in a popular 1990s funk song about a working-class man who falls victim to the violence ravaging the poor, predominantly black suburbs of Rio de Janeiro. “It’s just another Silva, without the shine,” the lyrics read.

When the whole society changes its perception

In the past, few Brazilians were proud of the Silva name. Many famous figures, including Ayrton Senna da Silva, a legendary Formula 1 driver in the 1980s and 1990s, quietly dropped the Silva name from their names.

But as Brazil rethinks how its brutal past helped shape the country's identity, a growing number of influential figures are promoting the idea that there is nothing shameful about being a “Silva.”

The success of celebrities, such as mixed martial artist Anderson Silva or soccer star Neymar, has also contributed to changing old perceptions of the name Silva.

“Today we are everywhere,” Rene Silva, an activist from one of Rio de Janeiro’s largest favelas and a television host who specializes in showcasing social success stories, told the New York Times. “It shows that we are fighters – and we are winning.”

Brazil's most famous soccer player, Neymar da Silva Santos Júnior, center, with his mother, Gonçalves da Silva Santos, in Barcelona in 2022. Photo: New York Times

The popularity of the Silva name is evident in any office space, such as a busy notary office in Rio de Janeiro. Behind the reception desk, Tiago Mendes Silva, a 39-year-old office worker who inherited his name from both parents, stamps and seals documents.

“There are always one or two Silvas here,” said Mendes Silva, one of seven employees at the notary office. Across the counter, Juscelina Silva Morais, a 59-year-old canteen worker, was handing over a document she needed legalized. “The name is part of our story,” she said. “It’s very Brazilian.”

Mr. Santos da Silva, the antiques dealer, was there with his partner, Tamiê Cordeiro, to apply for a marriage license. “I’m not a Silva yet,” Ms. Cordeiro, 27, joked. “But I will be soon.”

In fact, despite being associated with a slave-related ancestry, Silva has a special place in Brazil’s elite. At least four Brazilian politicians and lawmakers have the name, according to data from The Public Agency, a nonprofit investigative channel that recently mapped the ancestry of Brazil’s most powerful people.

"Because Silva is the name of the people"

Some historians trace the name Silva back to Roman times, where there is a record of a general with the name. Others link it to noble families in the Iberian Peninsula, in what is now Spain and Portugal, during the reign of the Kingdom of León, founded in the 900s.

Derived from the Latin “selva” or wilderness, the name Silva became popular in the 11th and 12th centuries among people who lived and worked near the forests in that area.

“There are many possible origins,” says Viviane Pompeu, a genealogist who runs a company that helps Brazilians trace their ancestors. “But we find that the roots always come from a place in the forest, in the jungle.”

The name Silva entered Brazil with colonization, with the first record dating back to a Portuguese settler in 1612. Notaries began keeping track of names about a century later, and since then, nearly 32 million Brazilians have been registered with the name Silva.

Scholars say African slaves who arrived in Brazil by ship were sometimes baptized by priests and given the name Costa (“coast” in Portuguese) for those who went to coastal cities and Silva for those who went to plantations in the country's jungle regions.

Wealthy landowners named Silva also often gave surnames to the people they enslaved, sometimes adding the preposition “da” (“of” or “belonging” in Portuguese) to represent them as property.

“Carlos da Silva, for example—he belonged to someone in the Silva family,” explains Rogério da Palma, a professor at Mato Grosso do Sul State University and author of a book on racism in Brazil after the abolition of slavery.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva considers his surname Silva to be the name of the people. Photo: AP

Even after Brazil abolished slavery, the number of people with the surname Silva continued to grow. Freed slaves who registered for the first time sometimes took the names of the landowners who had enslaved them and continued to rent them in exchange for food and shelter.

“It was a way of belonging,” Dr. Palma said. “It was also a loyalty to the family that owned the slaves.”

More than a century later, echoes of this past resurface in Daniel Fermino da Silva's own family tree. A history buff, Fermino da Silva, 45, spent more than three years searching for traces of his ancestors in archives and libraries. Ultimately, he discovered a family history "tied to the history of Brazil."

On his mother's side, he came from wealthy landowners in São Paulo who owned many slaves. On his father's side, records from the 1700s show that his Silva ancestors were enslaved some 800 kilometers away, in the mineral-rich state of Minas Gerais.

“I consider my family and ancestors heroes,” said Fermino da Silva, an engineer from the southern Brazilian city of Londrina, referring to his paternal side.

It remains unclear how Brazil's current president, the son of illiterate farmers from the country's impoverished northeast, inherited the country's most popular name.

During colonial rule, the region where President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was born saw an influx of Jewish refugees and other migrants fleeing religious persecution in Portugal. In search of new identities – and anonymity – historians say many of the newcomers changed their name to Silva.

Some scholars believe that may be how Mr. Lula (President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is often referred to simply as Lula in Brazil) became a Silva. But genealogists have struggled to trace his lineage with certainty.

“It is a big mystery,” said historian Fernando Morais, Mr Lula’s official biographer, who has tried to piece together the president’s family history.

President Lula doesn't seem to mind. A former union leader, Mr Lula sees himself as "just another Silva", according to historian Morais. "Because it's the name of the people".

Nguyen Khanh

Source: https://www.congluan.vn/vi-sao-5-trieu-nguoi-brazil-mang-cai-ten-silva-post324402.html

![[Photo] Lam Dong: Images of damage after a suspected lake burst in Tuy Phong](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/02/1762078736805_8e7f5424f473782d2162-5118-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the second meeting of the Steering Committee on private economic development.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/01/1762006716873_dsc-9145-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)