India, the world’s largest rice exporter, has banned exports of non-basmati white rice since July 20 in an effort to control domestic food prices and “ensure adequate domestic availability of rice at reasonable prices.” The ban is pushing up global rice prices and has a major impact on consumers in Asia and Africa.

Why did India ban rice exports?

India has banned the export of regular rice in an effort to curb soaring domestic prices. The move comes after reports and videos of panic buying and empty shelves in the US and Canada of Indian rice, sending prices soaring, according to the BBC.

|

| Indian farmers grow rice to meet domestic consumption and export demand. Photo: midilibre.fr |

“India’s rice export ban has caused global rice prices to skyrocket,” said Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). India’s rice export ban also came at an inopportune time.

Global rice prices have been rising steadily since the start of 2022, explained Shirley Mustafa, a rice market analyst at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). In India, rice prices have increased by more than 30% since October last year. Statistics show that, while a ton of regular rice in India cost around $330 in September last year, it has now reached $450. Rising rice prices have increased political pressure on the government ahead of next year's general elections. In addition, with a series of state elections in the coming months, the rising cost of living poses a challenge for the government.

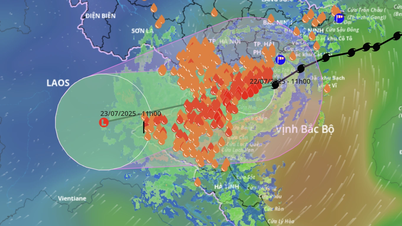

Supply is also under pressure as the new crop will not be available for about three months. Poor weather in South Asia, with scattered monsoon rains in India and floods in Pakistan, has also affected supply. Rice production costs have risen due to higher fertilizer prices. Currency depreciation has also increased import costs for many countries.

Devinder Sharma, an agricultural policy expert in India, added that the reason for India’s rice export halt was because the southern rice-growing regions were at risk of dry rains (rain that does not reach the ground, usually due to evaporation) during the El Nino weather pattern in the latter months of the year. Mr. Sharma believes that the Indian government is trying to anticipate the expected production shortfall.

|

India is the world's largest rice producer, accounting for more than 40% of global rice exports. Photo: Reuters |

Food export bans are not new. In October 2007, India imposed a ban on the export of regular rice, which was lifted and re-implemented in April 2008. The move caused rice prices around the world to rise by nearly 30% to record highs.

Since the conflict in Ukraine, the number of countries imposing food export restrictions has increased from three to 16, according to IFPRI. Indonesia has banned palm oil exports, Argentina has banned beef exports, and Türkiye and Kyrgyzstan have banned a range of grain products. Experts warn that India’s rice export ban poses a greater risk. The ban “will certainly lead to a spike in global white rice prices” and “will have a negative impact on food security in many African countries,” according to Ashok Gulati and Raya Das of the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), a Delhi-based think tank.

Africa is greatly affected

According to BBC, India is the world's largest rice producer, accounting for more than 40% of global rice exports. Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan and the US are also on the list of major rice exporters in the world.

Major importers of Indian rice include China, the Philippines and Nigeria. Other buyers, such as Indonesia and Bangladesh, also buy large quantities of rice as they face shortages at home. In Africa, rice consumption is high and growing. In countries such as Cuba and Panama, rice is a major source of energy in household meals. In some other countries, at least 90% of rice imports come from India.

In many African countries, India’s share of rice imports exceeds 80%, according to IFPRI. The rice export ban will mainly affect vulnerable people who spend a large portion of their income on food. “Higher prices may force them to reduce their daily food intake, switch to less nutritious alternatives, or reduce spending on other basic necessities such as housing and food,” Mustafa said.

Last year, India exported 22 million tonnes of rice to 140 countries. Of this total, 6 million tonnes were made from relatively cheap Indica white rice. India has stopped exporting Indica rice. This follows a ban on broken rice exports last year and the imposition of a 20% export tax on regular rice.

India currently has a stockpile of about 41 million tonnes of rice, three times the required reserve. This is stored in strategic reserves and the public distribution system (PDS), which provides access to cheap food for more than 700 million poor people. “I think the ban on exports of ordinary rice is essentially a precautionary measure. I hope it is temporary,” said Joseph Glauber of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

When will the rice market stabilize?

Thailand is the world’s second-largest rice exporter after India. On August 2, the Thai Rice Exporters Association (TREA) predicted that the instability in the rice market will last until the second half of 2023.

Several rice-producing countries are bracing for an El Nino-induced drought expected later this year and into 2024, according to TREA Honorary President Chukiat Opaswong. El Nino is triggered by a rise in surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean, leading to a period of global warming. The natural phenomenon typically occurs every two to seven years and results in less rainfall in Southeast Asia and southern Australia.

|

| Thailand is the world's second largest rice exporter. Photo: toutelathailande.fr |

Chukiat said that in addition to monitoring India’s rice export policy, Thai exporters should also monitor the rainfall situation and plan accordingly, especially during the harvest season in December. Under normal conditions, Thailand produces about 20 million tonnes of rice annually, of which about 12 million tonnes is consumed domestically and 7-8 million tonnes is exported. The impact of El Nino could reduce production by 1-2 million tonnes, which would increase export prices. However, it is unlikely that Thailand will ban rice exports.

In a new move, Thailand’s Office of National Water Resources (ONWR) on August 3 urged farmers across the country to switch to “less water-intensive crops that can be harvested quickly.” ONWR Secretary-General Surasri Kidtimonton said cumulative rainfall was 40 percent lower than normal, indicating a high risk of water shortages. Water management in Thailand should “focus on drinking water,” as well as “water for farming, mainly for perennial crops.”

Perennials are plants that grow again after harvest and do not need to be replanted every year, unlike annual crops. Rice is considered an annual crop. For every kilogram of raw rice grown, an average of 2,500 liters of water is needed. In comparison, alternative crops such as millet require 650 to 1,200 liters of water for the same amount of harvest.

If Thai farmers follow the above recommendations, rice production in Thailand could drop significantly. This could lead to further increases in global rice prices in the future. However, according to Oscar Tjakra, chief analyst at Rabobank, Thai farmers may still choose to grow rice due to the current environment with high export prices globally.

PHUONG LINH (according to BBC, RFI, gavroche-thailande.com)

*Please visit the International section to see related news and articles.

Source

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man visits Vietnamese Heroic Mother Ta Thi Tran](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/20/765c0bd057dd44ad83ab89fe0255b783)

Comment (0)