They left Vietnam at a young age, carrying with them the desire to study in the world's leading centers of knowledge.

Years later, with PhDs in hand and experience from prestigious laboratories, they faced a crossroads:

“Continue to be a link in the giant machine of international science , or return to create value for yourself in your homeland.”

When barriers and difficulties still exist, the decision to return always comes with concerns and calculations:

- A plan thorough enough so that when you return home you won't be "shocked" and disappointed?

- Between the opportunity to stay and the challenge of returning home: What to accept?

- When should I go back?

In conversations with young scientists who chose to return to serve their homeland, the answers to those concerns gradually became clear, from the preparation plan to the time chosen to return.

Contrary to popular belief, a PhD from a top university in the world is considered a “passport” that guarantees a stable career with desirable benefits.

In reality, the international academic environment is much harsher.

In these environments, obtaining and maintaining a research position requires fierce competition, constant demands on the quantity and quality of publications, the ability to attract research funding, and the pressure to maintain high levels of performance over long periods of time.

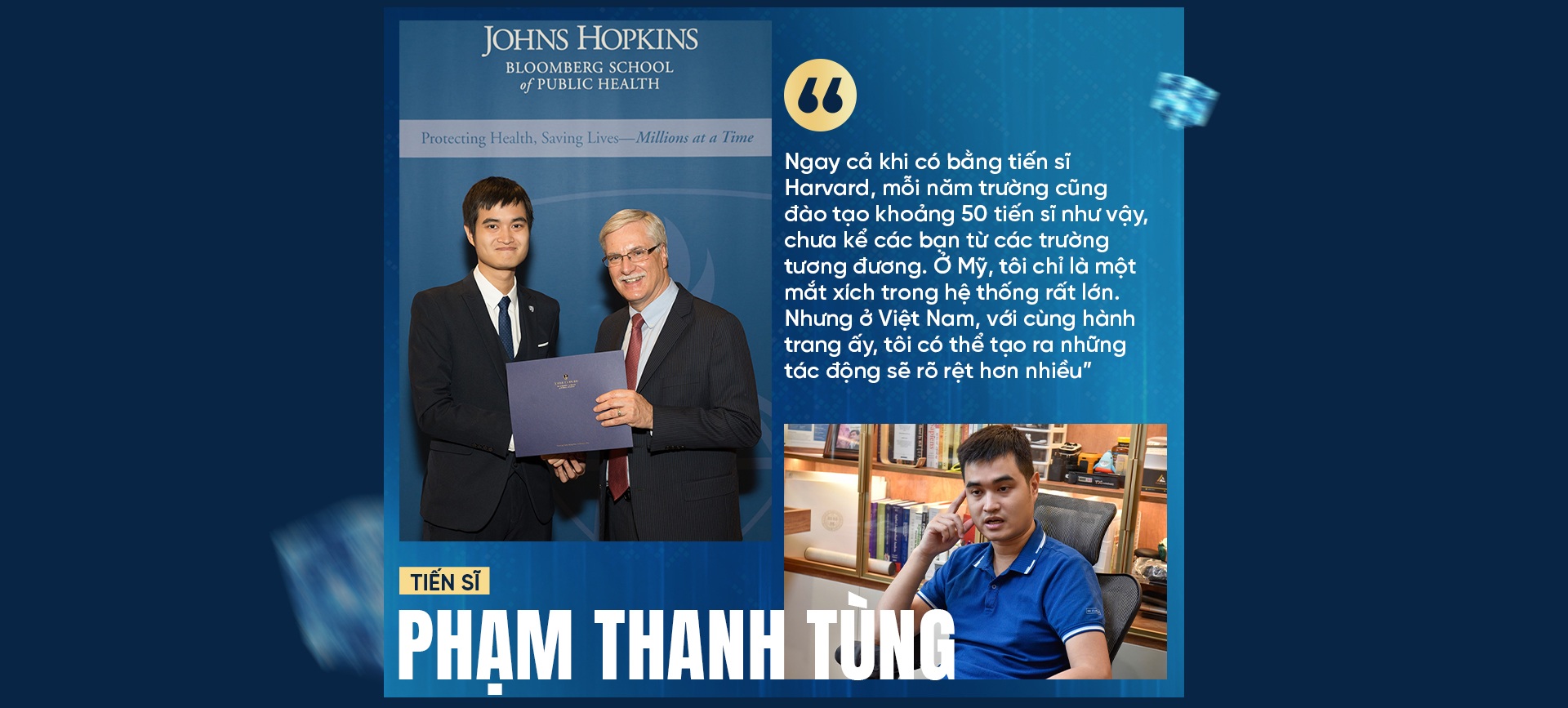

Dr. Pham Thanh Tung is one of the young scientists with a clear goal: to study abroad to accumulate knowledge, then return to contribute to his homeland.

Coming from a general practitioner background at Hanoi Medical University, he specialized in public health and epidemiology, completing his master's at Johns Hopkins before continuing his doctoral studies in cancer epidemiology at Harvard.

During his 5 years in the US, the young doctor soon realized that the picture was not as "rosy" as many people thought.

He said that compensation abroad depends on the position and the working environment. At large schools like Harvard or Johns Hopkins, teaching positions are rare and fiercely competitive, with constant performance reviews required.

After 3-5 years, lecturers must meet publication and research funding targets, otherwise it will be difficult to continue working.

The Harvard 9x PhD also shared that many of his friends after graduating often work in outside companies, pharmaceutical companies, and NGOs. These jobs are generally stable, with good salaries. However, the number of positions recruited each year is not much.

“Despite having the opportunity to find a stable job abroad, my family and I still decided to return to Vietnam. Firstly, the environment there is very competitive. Even with a Harvard PhD, the school trains about 50 PhDs each year, not to mention students from equivalent schools.

In the US, I am just a link in a very large system. But in Vietnam, with the same background, I can create much more obvious impacts,” he shared.

Although coming from two different fields, public health and applied mathematics, both Dr. Pham Thanh Tung and Dr. Can Tran Thanh Trung share one thing in common: the choice to return to Vietnam was not spontaneous, but a carefully considered plan, with the expectation of creating a greater impact in their homeland.

Dr. Trung - a 9x guy who returned from the California Institute of Technology and is teaching at the University of Natural Sciences in Ho Chi Minh City also shares a realistic view.

While domestic material conditions are still limited, Trung sees an important driving force from policy.

“In the US, young scientists in their own countries are also facing greater pressure than before. Meanwhile, I see positive changes in Vietnam. The government is increasingly focusing on attracting and retaining talent.

Programs like VNU 350 or national science projects have shown concrete efforts to create a more favorable environment for talented young people,” Dr. Trung expressed.

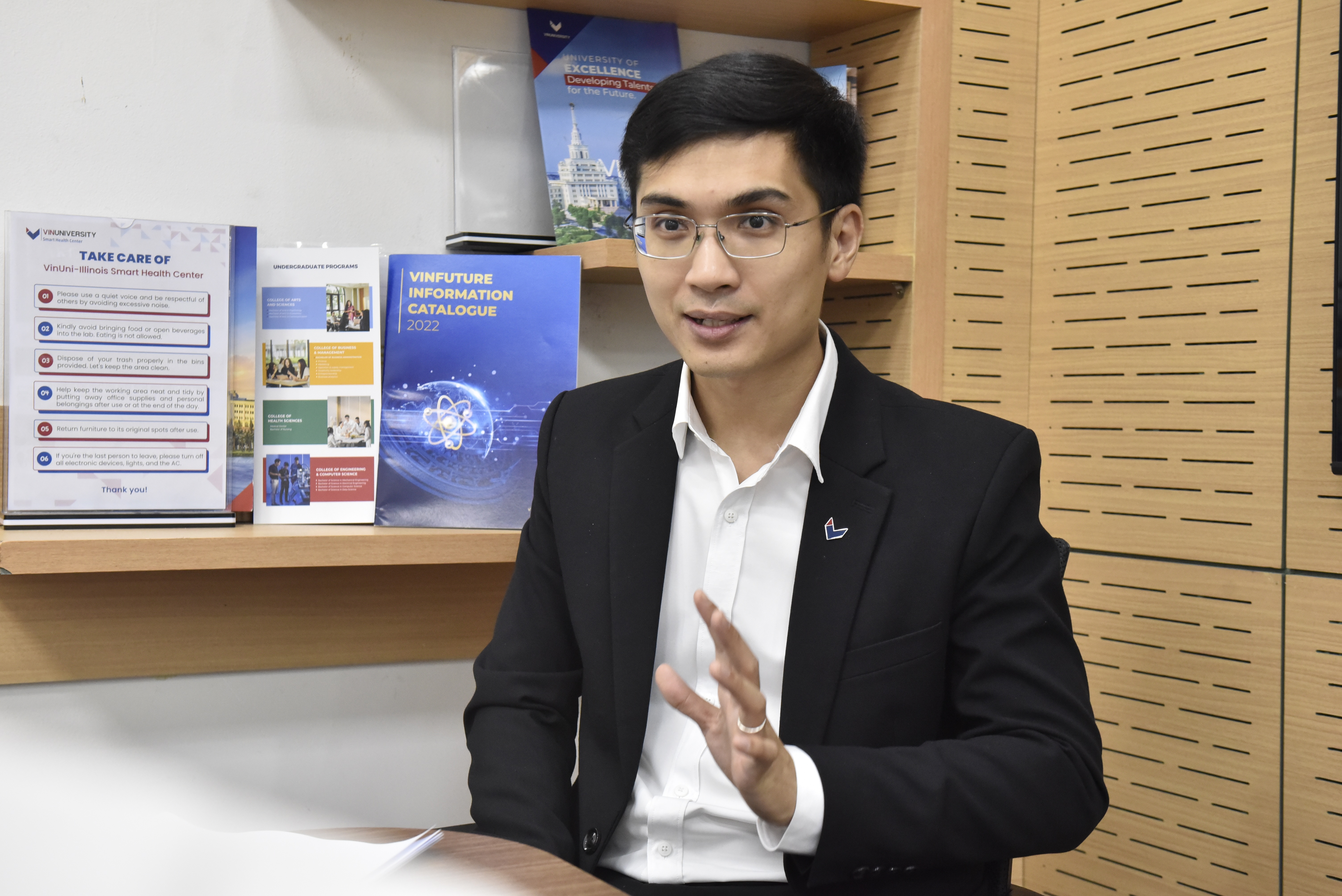

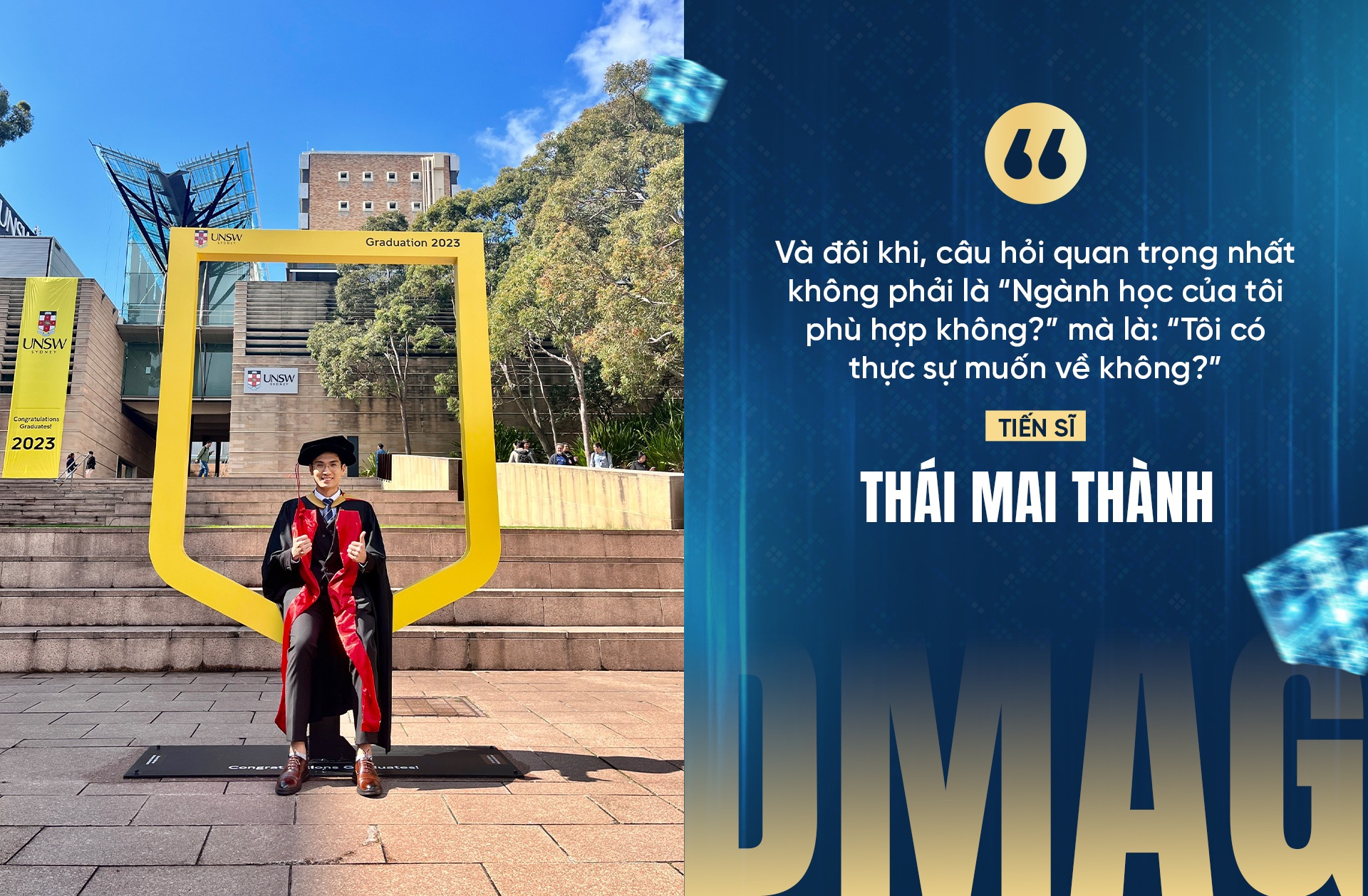

Sharing the same perspective on international challenges, Dr. Thai Mai Thanh, currently a lecturer at the Mechanical Engineering Program, Institute of Engineering and Computer Science, VinUni University, shared: “When the general context is difficult, funding for research projects is also more limited. Abroad, except for lecturers or tenured professors, most postdoctoral researchers only work when there is a funded project.”

According to Dr. Thanh, becoming a professor abroad is a challenging journey and requires great effort. Among the large number of Vietnamese who study abroad, only a very small percentage can stay and stand on the podium as professors. The majority must turn to other paths, even though the salaries and working conditions in developed countries are still attractive.

“What I am wondering is: if we put all our energy into competing in a large machine, why not use that same energy to build an internationally-standard lab right here in Vietnam?”, Dr. Thanh expressed.

He also added that we were not born and raised in the host country, so our relationships and support networks are more limited.

For truly outstanding people, top 5-10% in the world, they can overcome most barriers and the path to stay is feasible.

“But for those who are in the top 10%, not too outstanding but still have a lot of potential, why not return to Vietnam? A place that always welcomes them and allows them to create a more obvious impact,” said Dr. Thanh.

And that is the reason why, after completing his PhD in Biomedical Engineering at the University of New South Wales (Australia, 2023), the young man decided to pack his bags and return home.

Three stories, three different fields, but all have one thing in common: The decision to return was carefully considered between international environmental pressure and the desire to create long-term value for the homeland.

If the decision to return is an option, making it a reality requires a long preparation process.

Young scientists study at the world's leading knowledge centers with a clear plan, not only for their personal journey, but also for the long-term development of Vietnamese science.

This is clearly shown in the way they prepare conditions before returning home. Not every field can develop effectively in Vietnam's conditions and if not clearly defined from the beginning, the return can easily fall into a passive position.

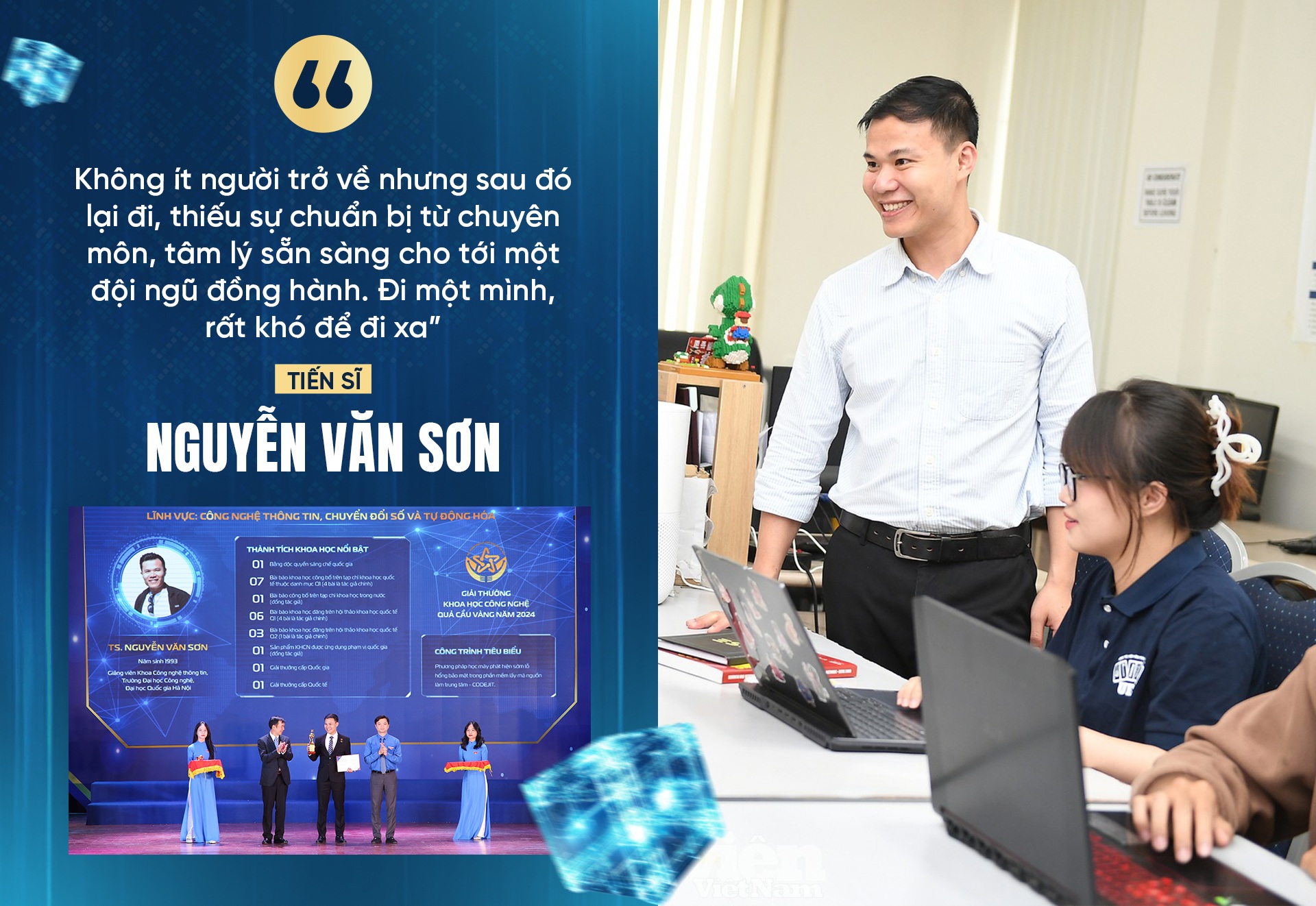

In 2017, when he won a research scholarship at the University of Texas (Dallas, USA), Nguyen Van Son (born in 1993, lecturer at the University of Technology) had a series of opportunities in the land of the stars and stripes.

But instead of continuing on that path, he chose a different path: returning home. In 2019, when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, the young 9X doctor asked himself: “What do I really want, and where can I create the greatest value?”.

The answer led him to a plan that did not start from zero. He and his colleagues began building a research team, implementing AI projects and automation software while still abroad.

3 years later, when he returned, he entered an ecosystem that he had "sown" before: had teammates, had projects, had direction.

For Dr. Son, that is the strategy when returning.

“Many people return but then leave again, lacking professional preparation, mental readiness, and a team to accompany them. Going alone, it is very difficult to go far,” the young doctor expressed.

For Dr. Son and Dr. Mai Thai Thanh, returning home is not a sudden turn, but a pre-calculated acceleration.

Each step is like laying a brick, creating a solid foundation so that when they return, they can get to work right away, instead of starting from zero.

Dr. Thai Mai Thanh also planned 2 years before graduation. He clearly determined that he wanted to become a research lecturer, not just a teacher.

Observing the domestic university environment, he noticed that most lecturers spend more time teaching than doing research, while abroad, this ratio is often reversed.

Therefore, Dr. Thanh's preparation phase is not only about personal arrangements, but also connecting with domestic facilities to ensure that when he returns, he can start working immediately.

“I can’t say I graduate today and go home tomorrow. Two years before I left, I envisioned the path I wanted to take and gradually created conditions for it,” he said.

The stories of Son, Thanh and many other scientists show that repatriation is not just a trip back, but a journey of laying each brick, from knowledge, experience, and a network of collaborators to build a solid foundation, capable of adapting and being proactive in conditions in Vietnam.

According to People's Teacher, Professor, Dr. Dang Thi Kim Chi - former Deputy Director of the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, choosing the time to return should not be viewed as a pressure to "return immediately" on young scientists.

“It is not necessary to return immediately after graduation. Staying for a few years to gain experience, training in an international environment, and then returning as an expert with the ability to implement and manage is also a very valuable way to contribute,” she shared.

This depends on the specific field. There are industries in Vietnam that are not yet developed, and do not have the conditions to apply knowledge immediately, so young people need to stay and continue to work practically.

“The important thing is not to come back early or late, but to come back on time,” Professor Kim Chi concluded.

Dr. Pham Thanh Tung said that from the beginning, he determined his goal of working in Vietnam and this goal guided the entire process of choosing topics, majors and skills.

He gave an example: If you research basic physics and need a particle accelerator, a device that only a few places in the world have, it is very difficult to develop well in Vietnam.

Therefore, right from the initial selection stage, researchers need to consider the match between personal expertise and the domestic scientific ecosystem.

From personal experience, he advises Vietnamese university graduates to spend a few years working in the country before going abroad for graduate studies.

This period of time helps them understand the labor market and domestic needs, thereby determining which skills they learned abroad will "take root" after returning, avoiding the situation of "not being able to use them after studying".

Dr. Can Tran Thanh Trung also gave an example: to develop an artificial intelligence system like a large-scale chatbot, not only does it require a team of good experts but it also requires a strong data center, investment in high-performance GPUs and expensive hardware.

In many countries, top universities often do not have enough budget for these items, so scientists tend to move to work at technology corporations to take advantage of those resources.

From there, Dr. Trung emphasized: the feasibility of research depends not only on people, but also on the specific field, expertise, technological products and how long it takes to achieve.

For Dr. Trung, the nature of his work is still mathematics.

Products like chatbots also originate from basic math problems, and to do math, he only needs a board, chalk, and a few passionate, persistent colleagues.

But he admitted that not all research directions are so "minimalist", and many other fields will face major obstacles if domestic infrastructure cannot keep up.

From another perspective, Dr. Thai Mai Thanh believes that not everyone has the conditions to choose the optimal major for returning home.

In reality, most graduate students cannot choose their ideal research lab from the start, but have to apply to many places and then stick with the one that accepts them.

“Not every story starts with an ideal choice,” said Dr. Thanh. Therefore, the deciding factor is the ability to adapt and pivot professionally.

Dr. Thanh cited that in the US, many professors, although starting from a specific major, within 20 years of working, have expanded to many other research directions, even far from the topic when graduating.

For those who aim to return home, proactively accumulating additional knowledge and finding ways to change direction is a must.

And sometimes, the most important question isn't, "Is my major right for me?" but, "Do I really want to go back?"

If the answer is yes, there will always be a way. If not, there will be reasons to come up with another strategy.

Dr. Pham Sy Hieu, Institute of Materials Science, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, holds two doctorates: in Chemistry from the University of Artois (France) and in Science from the University of Mons (Belgium).

He believes that the common problem of all young scientists after a long time studying abroad is the ability to adapt.

In the international academic environment, openness, academic freedom and abundant resources create a certain working inertia.

For Dr. Hieu personally, it took more than a year of work after returning to readjust his research path.

Hieu's current research direction in Vietnam has changed a lot compared to when he was a PhD student.

That requires him to consolidate his basic knowledge while filling in the gaps to suit the domestic context.

He likened this to a process of “survival adaptation.”

“If a fish living in the sea cannot adapt to fresh water, it will not survive. The same goes for scientists. If they cannot adapt to fresh water, it will be very difficult to develop,” said the 9X doctor.

Fortunately for him, his master's and doctoral research directions are unified and complementary to each other, creating a sustainable foundation for continued development in Vietnam.

However, he emphasized: domestic facilities are still a limiting factor and any scientist needs to accept that reality to find ways to adapt, instead of expecting working conditions like in advanced Western laboratories.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/ban-ke-hoach-day-cong-gom-tinh-hoa-5-chau-ve-dat-viet-cua-tri-thuc-tre-20250825173538692.htm

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh receives President of Cuba's Latin American News Agency](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F01%2F1764569497815_dsc-2890-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![From working for hire to becoming a boss: [Lesson 5] Sending - learning - returning - creating](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/05/1762297489528_1546-anh-3-072934_320.jpeg)

Comment (0)