Researchers from the University of Copenhagen suggest that water appeared on Earth when the planet absorbed dust and ice during its formation.

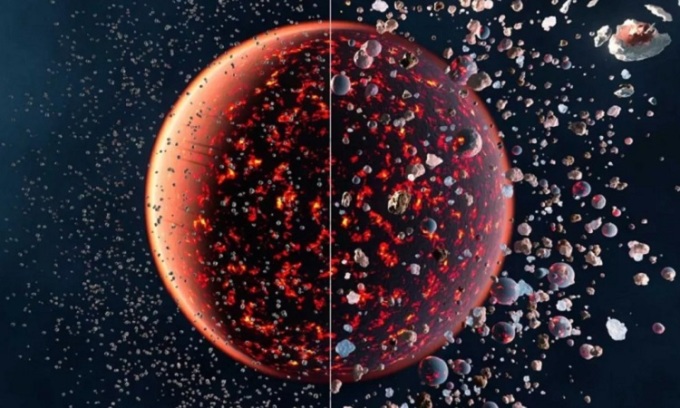

Simulation of the formation of the Earth from small pebbles. Photo: UHT Zurich

Earth may have formed much more quickly than previously thought, after being born as tiny pebbles a few millimeters in size that accumulated over millions of years. The new hypothesis also implies that instead of icy comets bringing water to Earth, the essential ingredients for life existed on the planet as the young Earth sucked up water from the environment in space. The conclusion has important implications for the search for life beyond the solar system, suggesting that habitable planets with water around other stars may be more common than currently thought. Isaac Onyett, a PhD student at the Center for Star and Planet Formation at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues published the study on June 14 in the journal Nature .

The team’s hypothesis suggests that about 4.5 billion years ago, when the Sun was a young star surrounded by a disk of dust and gas, small dust grains were pulled in by the forming planets once they reached a certain size. In the case of Earth, the process of drawing material from the disk of dust and gas ensured that the planet was supplied with water.

The disk also contains many ice grains. While the dust-sucking effect is taking place, it also absorbs some of the ice. This process contributes to the existence of water during Earth's formation, rather than relying on a random event that brought water to the planet 100 million years later.

“People have been debating how planets form for a long time,” says geochemist Martin Schiller of the University of Copenhagen, who was part of the research team. “One hypothesis is that planets form from collisions between multiple bodies, which gradually increase in size over 100 million years. In that case, the appearance of water on Earth would require a random event.”

Examples of such serendipitous events include water-bearing icy comets crashing into the planet late in its formation. “If that’s how Earth formed, then we’re pretty lucky to have water on Earth. So the chances of water existing on an exoplanet are pretty low,” Schiller says.

The team came up with the new hypothesis by using silicon isotopes as a measure of the planetary formation mechanism and the timescales involved. By examining the isotopic composition of more than 60 meteorites and planets, they were able to establish a relationship between Earth-like rocky planets and other bodies in the solar system.

The new theory predicts that if a planet orbits a Sun-like star at the right distance, it will have water, according to Professor Martin Bizzarro of the Globe Institute, co-author of the study.

An Khang (According to Space )

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh launched a peak emulation campaign to achieve achievements in celebration of the 14th National Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/8869ec5cdbc740f58fbf2ae73f065076)

![[INFOGRAPHIC] iReader Smart X3 E-reader and "digital assistant"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/00bbaa95954a4c7bbd03b86cb5acac07)

![[Photo] Bustling Mid-Autumn Festival at the Museum of Ethnology](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/4/da8d5927734d4ca58e3eced14bc435a3)

![[VIDEO] Summary of Petrovietnam's 50th Anniversary Ceremony](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/4/abe133bdb8114793a16d4fe3e5bd0f12)

![[VIDEO] GENERAL SECRETARY TO LAM AWARDS PETROVIETNAM 8 GOLDEN WORDS: "PIONEER - EXCELLENT - SUSTAINABLE - GLOBAL"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/23/c2fdb48863e846cfa9fb8e6ea9cf44e7)

Comment (0)