Towards the end of the Meiji era, particularly during the decade of 1905-1915, many great writers emerged. The number of outstanding writers of this particular decade far surpassed the number of great writers from the 1920s until the end of World War II.

Literature during the Meiji period

Towards the end of the Meiji era, particularly during the decade of 1905-1915, many great writers emerged, such as Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Shiga Naoya, Yokomitsu Riichi, and Kawabata Yasunari. Some writers belonging to the "proletarian literary movement" also engaged in political activism, including Tokunaga Sunao, Hayama Yoshiki, and Kobayashi Takiji.

The number of outstanding writers of this particular decade far surpasses the number of great writers from the 1920s to the end of World War II. This period saw many movements: Neorealism, Sensationalism, Naturalism, Symbolism, Surrealism... Each movement further divided into many smaller tendencies and schools.

***

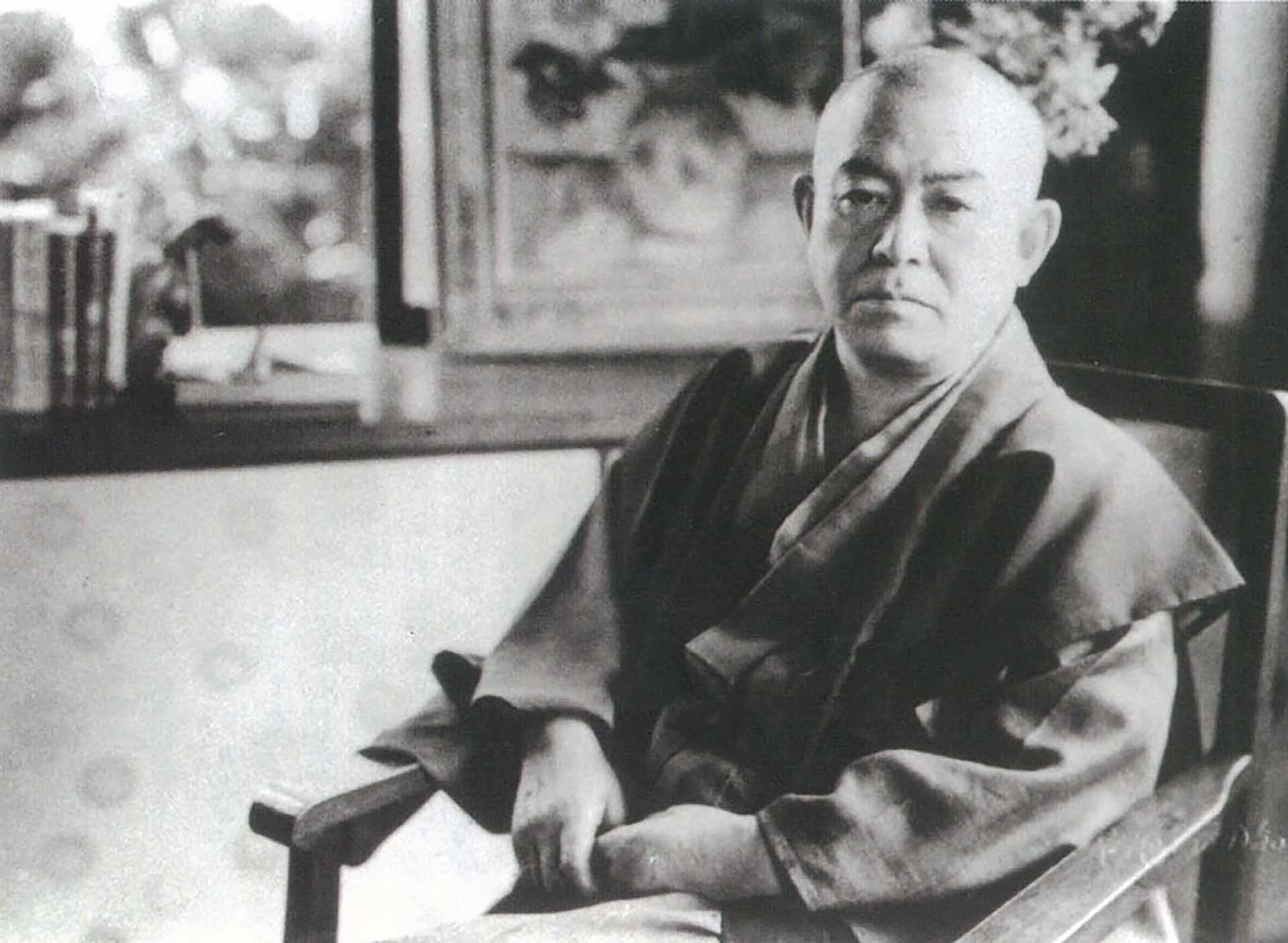

|

| Writer Tanizaki Jun'ichirō. |

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō (1886-1965) wrote about the internal conflicts between East and West. He sought beauty rather than morality as before. He subtly depicted the dynamism of family life against the backdrop of rapid changes in 20th-century Japanese society, and was one of the six authors on the final shortlist for the 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature, the year before his death.

His novels are marked by morbid sexuality and a very Westernized aestheticism. He went against the trend of autobiographical writing that emphasized the self and returned to traditional aesthetic principles.

The novel *Chijin no Ai* (1925) depicts a respectable engineer husband who falls in love with and marries a very young, Westernized, capricious woman who enjoys tormenting him. He becomes her slave and finds pleasure in torturing her.

The Key (Kagi, 1956) tells the story of a 56-year-old university professor and his 55-year-old wife. They secretly keep diaries, though they know they are reading each other's. The husband, feeling sexually impotent, tries to stimulate himself by creating jealousy. The wife also subtly and consciously plays along, allowing her husband to rediscover pleasure; he becomes so obsessed that he dies.

Some of Tanizaki's other major works include: Unicorn (Kirin, 1910), Shōnen (Children, 1911), Akuma (Demon, 1912), Manji (Swastika, 1930), Love in the Dark (Mōmoku Monogatari, 1931), and Yume no Ukihashi (Dream Bridge, 1959)...

***

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (1892-1927) was a modern writer, famous both internationally and abroad, especially since the film adaptation of his novel Rashōmon (1915) won international awards. He studied English literature, taught English, and wrote. He attempted to blend European and Japanese cultures.

Although deeply influenced by Western culture, he often drew on a wide variety of themes from classical Japanese and Chinese literature. He left behind over 140 works (mostly short stories), essays, and poems. He took a different path from late 19th and early 20th-century Japanese literature, not pursuing Western themes or naturalistic, proletarian, and individualistic romantic tendencies (the literature of the Self).

His works return to traditional narrative roots but incorporate modern psychological analysis, objective descriptions, a blend of realism and fantasy, ornate yet concise writing, and a tight structure. He satirizes the stupidity, hypocrisy, and greed of the bourgeoisie in works such as "Mori Sensei" (1919) and "Tochi no Ichibu" (1924)...

In his later years, his work reflected a fear of uncertainty, stemming from his obsession with his mother's mental illness; he feared losing his creative ability. This was compounded by the crisis of the bourgeois intellectuals in the face of the rise of fascist militarism. He committed suicide by taking poison at the age of 35, leaving behind his wife and three children.

Some of his other major works include: Old Age (Ronen, 1914), The Nose (Hana, 1916), The Screen of Hell (Jigokuhen, 1918), The Spider's Web (Kumo no Ito, 1918), Autumn Mountain Landscape (Shuzanzu, 1921), In the Bamboo Grove (Yabu no Naka, 1922), Genkaku Villa (Genkaku Sanbo, 1927)...

In 1935, Kikuchi Kan (1888-1948), a friend of Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, a writer and publisher of the Shinshichō magazine, founded the annual Akutagawa Ryūnosuke Literary Prize, awarded to young writers. For nearly 90 years, the prize has remained a high honor for Japanese writers.

***

Shiga Naoya (1883-1971) was a writer who greatly influenced modern Japanese literature, recognized as a master of realism. His writing style combined beauty with subtle emotions and psychological analysis. His works are primarily autobiographical novels (from the first-person perspective), inspired by ordinary everyday events with meticulous detail, a genre very popular in modern Japanese literature.

For example, in the short story "In Kinosaki" (Kinosaki de, 1917), a young patient who has just survived a train accident, being treated at a mountain sanatorium, reflects on death and human fate when he sees a dead bee, a mouse thrown into the water while swimming, and a lizard accidentally thrown to its death.

In 1895, his mother died, and in the autumn of the same year, his father remarried—these events and the context for his autobiographical novel *The Death of My Mother and My New Mother* (Haha no Shi to Atarashī Haha, 1912).

He was also influenced by Andersen's fairy tales and wrote *Nanohana to Komusume* (1913), while the essay *Nairu no Mizu no Hitoshizuku* (1969) marked the end of his literary career.

Some of his other notable works include: At the Fortress Point (Ki no Saki Nite, 1920), Reconciliation (Wakai, 1917), The Apprentice's God (Kozou no Kami-Sama, 1920), The Dark Road at Night (Anyakouro, 1921 and 1937), Gray Moonlight (Hai'iro no Tsuki, 1946)...

(to be continued)

Source

![Strolling through the American Cultural Garden [Part 19]](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/1/19/282450858d7345568984c556f7bb952d)

![Strolling through the American Cultural Garden [Part 17]](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/1/20/d66f4bb035b24a638d3710594d9d915f)

Comment (0)