At the end of Van Chuong - Hang Bot alley (the section connecting to Van Huong alley), houses are now densely packed, and the roads are clean and smooth. However, in the 1960s and 70s, this area was entirely covered with vegetable fields planted on small mounds of earth, stretching from Luong Su village through the end of Van Huong and Van Chuong alleys all the way to Dam Lake (now the Van Chuong Lake area). In the 1970s, there was also an anti-aircraft artillery position located in the open space amidst the grassy fields and vegetable gardens.

In the early 1970s, my mother, along with Mr. Ho (whose house was at the beginning of Van Chuong alley) and Mr. Ung (whose house was at the end of the alley), pooled their capital to establish the Van Chuong Alley Noodle Production Group. Mr. Ho was formerly an official in the Dong Da District Handicraft Department. He was tall, energetic, and resourceful, serving as the group leader and technical worker; while Mr. Ung was fair-skinned, refined, and had previously taught, so we often called him "Teacher."

The noodle-making workshop was located in an open space at the end of Van Chuong alley. Calling it a "workshop" sounds impressive, but the production area was just a shack built of bamboo, with a tiny noodle-making machine in the center. The flour was kneaded and rolled repeatedly until it was incredibly thin, then cut into long strips, the width fitting perfectly into the cutting machine. The young men working for the workshop took turns operating the cutting machine, feeding the thinly rolled strips of dough into the machine. My mother would receive the noodles coming out of the cutting machine, spread them evenly on loosely woven bamboo trays, and then transfer them to the blazing charcoal stove at the end of the shack. The trays of noodles were stacked on top of each other and placed into a very large steamer over the fire, covered with a huge oil drum, and the hot steam would cook the noodles.

At that time, I had left home, but whenever I had time off, I would go to the noodle production team to help my mother and aunts. I was given the easier task than everyone else: operating the noodle cutting machine. Nowadays, noodles are elongated and round. In the past, noodles were square because the cutting machine consisted of two rollers with straight grooves, interlocking like a comb. The noodles passed through the rollers, forming strands with a square cross-section. The kneading and flattening process required skill. If kneaded too thoroughly, the noodles would stick together. If kneaded too dry, the noodles would break into small pieces right on the rolling machine, falling everywhere.

When the noodles were about to be cooked, the barrel was lifted from the pot. Steam billowed out. The worker, wearing gloves, took the trays of noodles out of the steamer, placed them on a rack, and then added another batch. Once, I tried a few warm noodles; the taste was slightly pungent. Nowadays, it might taste like chewing straw, but back then, the more I chewed, the sweeter and tastier they became.

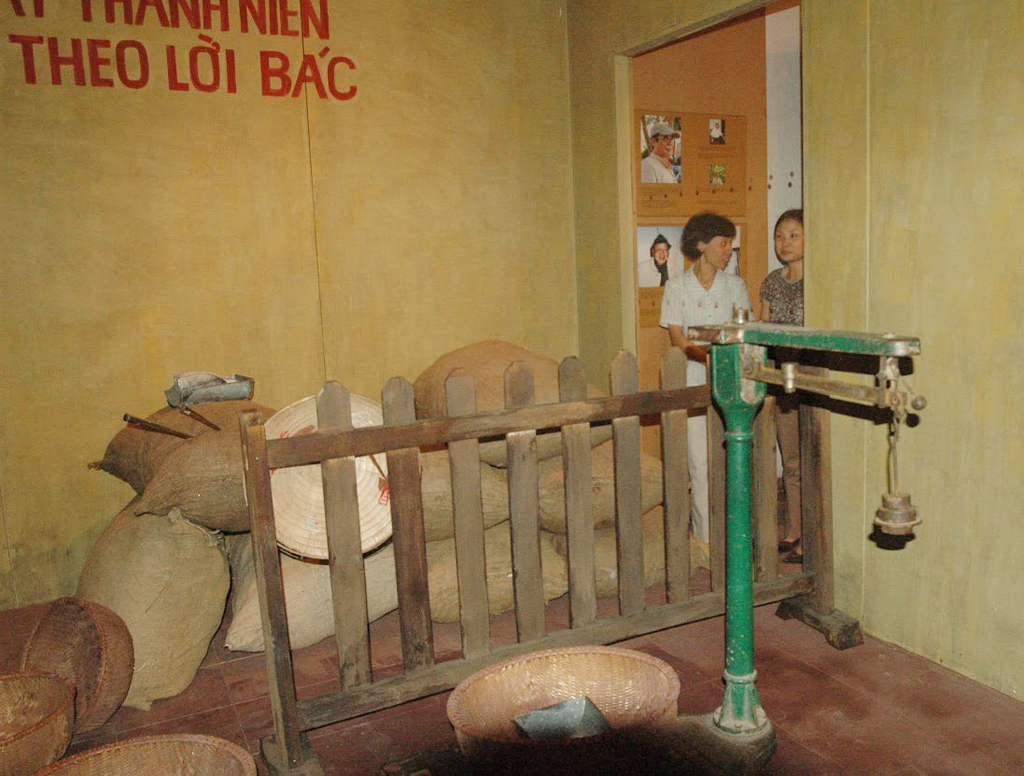

The steamed noodles are then taken out to dry. When they are almost completely dry, the workers weigh them before delivering them to customers.

As Tet (Vietnamese New Year) approached, the noodle-making cooperative put up an additional sign outside its door: "Processing of Crispy Rice Cookies." Nowadays, the sign probably includes the words "family recipe" to attract customers, but in the old days, even without advertising, people flocked to them with flour and sugar to have their crispy rice cookies made. The ingredients for crispy rice cookies were simple: wheat flour, palm sugar or white sugar, eggs, a little rendered fat, and if they had a piece of butter bought "illegally," it was even better. Some families were more extravagant and added milk to the cookies. But to get good quality flour, you had to wait until just before Tet, when the grocery store would sell each household a few kilograms of a different type of flour than the usual lumpy, smelly kind. Therefore, as Tet approached, families would bring their ingredients to have their crispy rice cookies made, patiently queuing for their turn.

In the noodle workshop, someone is responsible for receiving and weighing the ingredients, pouring them onto a table in front of the delivery person, then beating eggs, mixing in butter or lard, sprinkling in sugar and baking powder, and finally kneading them with the flour. Once kneaded, they push the dough to a corner of the table, attach a piece of paper with the customer's name, and leave it there to ferment. The table where the ingredients are placed also serves as the dough rolling table, positioned near the door where everyone can see and supervise the workers.

A recreation of a department store and a corner of a grocery store is featured at an exhibition about Hanoi during the subsidy period, held in Hanoi.

The risen dough was rolled out thinly and shaped into long strands, arranged on a metal tray, and awaited baking. In Hanoi at that time, there was only one type of mold: a long, slender shape similar to sampa bread, but with air vents drilled along the length of the bread. With air vents and enough dough in the mold, the bread would rise evenly. The dough that seeped into the air vents, when cooked, transformed into the bread's distinctive spikes, creating the iconic, crispy, spiky bread of the difficult subsidy era.

Back then, I often helped my mother and the other women in the group, but I wasn't allowed to participate in the dough kneading process because it was difficult. Besides the recipe, you also need the feel of someone experienced to bake batches of perfectly golden-brown bread with minimal crumbling.

At that time, Hanoi also had imported biscuits, sold in shops catering to mid-level and high-ranking officials. Even if they made it to the public, the price was very high, so homemade, crispy biscuits remained an indispensable treat in every household during the Lunar New Year.

My grandchildren are now indifferent even to imported cakes and candies, and they don't have to wait until Tet (Lunar New Year) to enjoy delicious sweets like the children in Hanoi used to. Perhaps now, few families still make their own cakes, but those crispy, spiky biscuits that were only eaten once a year, and the noodles shaped in the tiny workshops of the subsidy era, will always remain deeply etched in the memories of our generation, witnesses to a difficult time.

(Excerpt from the work "Hang Bot, a 'trivial' story that I remember" by Ho Cong Thiet, published by Labor Publishing House and Chibooks, 2023)

Source link

Comment (0)