Having just started working at the Mu Sang Commune Health Station (Phong Tho, Lai Chau) for 3 days, doctor Lo Thi Thanh (46 years old, from Dien Bien) went to the village to deliver a baby. It was an emergency birth, the mother was imprisoned by the placenta.

"The road at that time was not yet concreted, just steep and slippery slopes. Family members had to ride motorbikes to pick me up," doctor Thanh remembers clearly the images from 2007.

The car kept sliding down the slope as if falling straight into an abyss. When they arrived, doctor Thanh breathed a sigh of relief and said in a trembling voice: "Mom, I'm alive."

In Mu Sang commune, many women still choose to give birth at home. For them, giving birth is a woman's business, a family affair, without the need for cadres. They believe that giving birth where their mother gave birth, their child will also be born safely.

Thanks to Dr. Thanh's perseverance, that mindset is gradually changing. Pregnant women who used to be shy about wearing white blouses now proactively call out, "Ms. Thanh, I have a stomachache." Husbands who used to think that childbirth was a woman's business now quietly sit outside the clinic, waiting for their wives to give birth.

"If I give up, how can I expect people to change?", that question - for the past 18 years - has always been what keeps this woman in this highland land.

"Sometimes a family member comes over and calls me: Miss, someone is in labor in Sin Chai village," nurse Lo Thi Thanh began the story in a simple voice.

More than 20 years ago, Thanh graduated as an obstetrician in Dien Bien . After that, Thanh worked at the Mu Sang Commune Health Station.

At that time, she was only in her twenties, shy and unfamiliar with the place. "People looked at me as too young, many people said: How can you help someone who hasn't given birth yet?", Doctor Thanh recalled.

From the center of Mu Sang commune to the farthest village, it takes 15 kilometers to cross slippery rocky slopes, not to mention the difficult rainy season. The trip is sometimes not just about overcoming terrain, but a life-and-death race between life and death.

Mu Sang commune is nearly 40 km from the district center, 99% of the population is ethnic minorities.

Here, home births used to be as routine as cooking. There were no doctors, no midwives, no medicines or medical equipment. There was just a makeshift wooden house, a plank bed and a relative standing by - usually a mother-in-law or sister.

Mrs. Ma Thi My, now 85 years old, living in Han Sung village, said: "I gave birth to 10 children, all of them at home, without going to the clinic, without anyone consulting. At that time, no one knew what a doctor was, nor did they go to a shaman. Some people were lucky, but many people lost their children, some lost both mother and child."

Mrs. My's voice dropped: "I just know that when you're pregnant, you have to eat according to tradition, whatever is available. It's very difficult."

Lack of information, combined with deeply ingrained cultural beliefs, once made giving birth in the highlands a lonely and dangerous journey.

Superstitions and ignorance are so deeply rooted in the subconscious that access to healthcare has long been something strange, even… scary.

Being a midwife in Mu Sang is not just a matter of expertise. It is a matter of knocking on every door, finding a way to cross the boundary.

Throughout that journey, there were births that remained fresh in the female doctor's mind as if they had happened yesterday. One of them was a mother who had given birth four times that she especially remembered.

During the woman's third pregnancy, Dr. Thanh not only performed regular check-ups but also called her constantly to ask: "Are you planting in the fields today? Do you feel your belly cramping?"

If there was no phone at home, she would travel a long way to get there, just to remind them one more time: "If there is any strange sign, go to the station immediately."

But that night, at 2am, the husband rushed over and said: "Sister, my wife gave birth 30 minutes ago."

The female officer was stunned. In the morning, she had come in and carefully instructed that if there was any change, she must come to the station immediately.

"They said the road was difficult to travel, and they couldn't take their wife there," Doctor Thanh recalled. That was also what made the female doctor worry for a long time, even though she had given careful instructions, but Mu Sang was not an easy place to travel to or get to.

The mother had placenta imprisonment - a dangerous obstetric complication that, if not treated promptly, could lead to acute blood loss and death. Luckily, Dr. Thanh arrived in time.

In the following days, Dr. Thanh still visited to check if the mother had a fever or postpartum complications.

"If people don't come to me, then I'll go to them," the female doctor in the border area recounted. "Here, the villagers are often upset. I only dare to tell you two, fortunately this is easy. If it were difficult, we would have to go to the district or the province."

According to the female doctor, if she had not arrived in time that night, the pregnant woman would have had to be transferred directly to the Phong Tho District Medical Center. At that time, there was no other choice but to have a cesarean section.

But for people in the highlands, surgery is still something very strange and scary.

Then the same family, on her fourth birth, came to her again. But this time it was proactive, without needing to be persuaded.

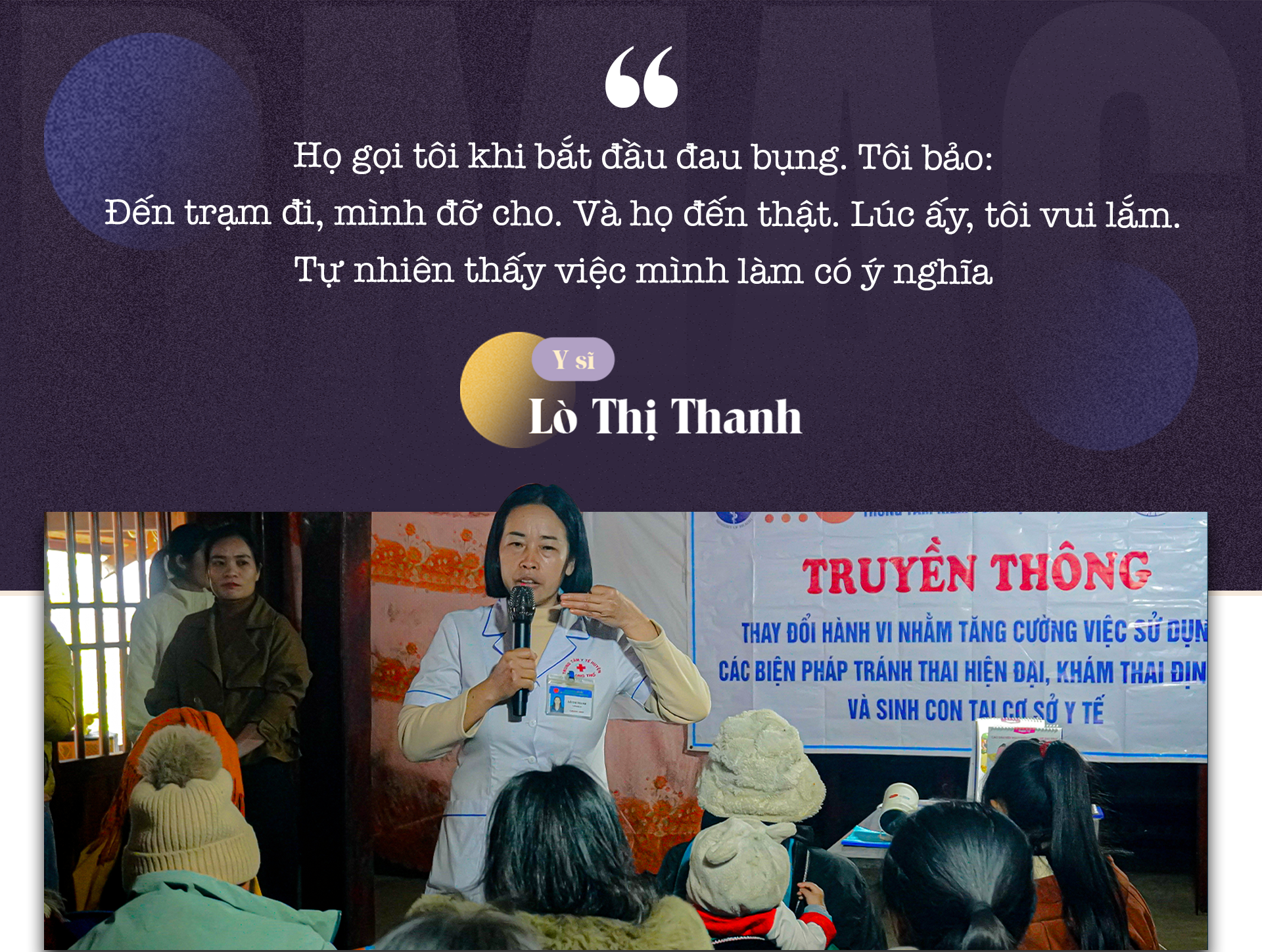

"They called me when they started having stomachaches. I said: Come to the station, I'll help you. And they did come. At that moment, I was so happy. Suddenly I felt that what I was doing was meaningful," doctor Thanh said with a smile.

That joy does not come overnight.

In the first days of working in Mu Sang, Doctor Thanh felt like he was standing in front of an invisible wall. It was not the steep slopes, nor the nights of labor in the rain and wind, but the most difficult barrier to overcome: language.

The people speak Mong, and she is Thai. Every time she comes to the village, doctor Thanh feels like she is lost in a strange world . She doesn't understand what the people are saying, and even less knows how to explain it to them so they believe and understand.

But then, this "white blouse" began to study by herself. Without books, her lessons were stories by the fire, and times following people to the market and fields.

Seeing a tree by the roadside, she asked: "What is this tree called in Mong language?".

Listening to women complain of pain, she listened to every word, every facial expression to guess and learn. The female doctor learned the names of vegetables, learned how to describe stomach pain in the Mong language, and learned ways to speak gently enough so as not to embarrass or make people feel shy.

"If we don't understand their language, how can we understand their fear and anxiety?", said doctor Thanh.

According to this woman, doing mass mobilization requires more than just expertise. It requires compassion. And that compassion often starts with knowing how to name a type of leaf in the local way.

Overcoming the language barrier is another challenge, which, according to this female doctor in the border area, is the most difficult: Superstition. This barrier is invisible, but it is deeply ingrained in every way of thinking and every rhythm of life in the highlands.

"The Mong people have had taboos that have been ingrained for generations. They believe that giving birth is a sacred and absolutely private matter for women, "no one can touch", "no one can see". The only person who can see is the husband", said doctor Thanh.

Therefore, for generations, mothers in the highlands have been accustomed to giving birth alone in a cold house, cutting the umbilical cord with a knife or sickle.

Therefore, prenatal and gynecological check-ups are both strange and embarrassing. "Many pregnant women who come for check-ups only dare to ask timidly: Is Ms. Thanh here?", the female doctor said.

At the district station, no matter how good the doctor was, if they didn’t know him, they would quietly turn away. Only Ms. Thanh - the woman they considered family - was close enough to make them open up. Because Dr. Thanh not only knew the medical profession, but also understood every house and every path they often walked.

Life is like a painting, not only bright colors. Many times, Doctor Thanh wanted to pack everything and return home.

The times she "bet" to go with the stretcher of the pregnant woman up the steep slope, both scared and tired, she thought: Maybe I should just...

Up here, the female doctor's husband is a teacher, but her two children still live in the countryside with their grandparents. They only come home once every 2-3 months.

Once, her husband advised her: "Why are you rushing into this? Get up in the middle of the night. Who is praising you?"

Remembering the times he struggled mentally with himself, Doctor Thanh suddenly fell silent for a moment.

"At that time, when her husband advised her, when she remembered the times when she thought she couldn't hold on anymore. What made her stay in this place for the past 18 years?", the reporter asked.

Doctor Thanh slowly replied, as if talking to himself: "Their lives are like that, quiet, deprived and enduring. If I also give up, I also turn my back, then I am no different from them. I cannot expect them to change if I myself do not persevere to the end."

The woman knew her husband loved her and her family needed her, but she still couldn’t let go. Every time she looked at the bewildered eyes of a woman giving birth for the first time, or the hand gently tugging at her shirt when she had a stomachache in the middle of the night… she couldn’t bear to leave.

Difficulties still remain: remote areas, scattered houses, dangerous nighttime travel, language barriers, and customs. But there is also new confidence: young people who have finished grade 9 are different, women are gradually becoming more courageous and have children who grow up healthy thanks to the hands of doctor Thanh.

Now, nearly 70% of pregnant women in the commune know how to go for regular prenatal check-ups.

Once unfamiliar concepts such as "ultrasound", "iron pills", "first trimester pregnancy check-up" have gradually become familiar, mentioned in conversations in kitchen corners and alleyways. Since the day doctor Thanh came to the station, Mu Sang has never had a case of maternal death.

Not only is she a prenatal and delivery doctor, she also regularly organizes talks at the village's cultural house. The place where people in the border area still call it by the familiar name: "Miss Thanh's propaganda session".

There, Dr. Thanh talked about nutrition for pregnant women, danger signs during pregnancy, and how to keep newborns clean. At first, many mothers just came for the sake of it. But then, they started asking questions and listening.

And fortunately, men - who used to consider childbirth a woman's business - are now different.

Mr. Ma A Phu (35 years old) living in Sin Chai village is one of them. In 2010, his wife gave birth safely at the clinic, thanks to the patient persuasion of doctor Thanh.

15 years later, when the good news suddenly knocked on the door again, the couple did not hesitate: "This time is the same as last time, everything depends on Ms. Thanh," Mr. Phu shared.

Since then, every propaganda session has seen Mr. Phu sitting and listening. "Sometimes, when the villagers are busy and cannot go, they come back and ask: What did Ms. Thanh propagate today?", Mr. Phu recounted.

"When men start to care about childbirth, I know there is hope," Dr. Thanh laughed.

Once reserved and fearful, Giang A Lung (22 years old) and his wife living in Sin Chai village have gradually changed. His wife gave birth to their first child at home because their grandparents were the same way.

"Because it was our first child, my wife and I were very worried, but in the past, my parents and grandparents still gave birth at home, so when it was my wife and I's turn, we chose to give birth at home like our grandparents," Mr. Lung shared.

Mr. Lung admitted: "Giving birth at home is very unhygienic, but because there was no propaganda at that time, many families did not go to the health station because they thought it would cost a lot of money."

Sometimes, change begins with the image of a mother hearing her baby's heartbeat for the first time through a fetal heart monitor, a baby being born on a clean bed, with doctors and nurses by her side.

Those seemingly small things, but in Mu Sang, are a journey through forests, mountains, and prejudices.

However, not all villages have crossed the old line. In some places, early marriage and childbearing are still part of a deeply ingrained way of life.

Giang Thi Su (18 years old) living in Sin Chai village is one such case. Su got married right after finishing 9th grade, at only 16 years old.

Luckily, Su met Dr. Thanh. She was counseled, had her pregnancy monitored, and was taken to the district health center to give birth. Dr. Thanh still sees many cases like Su's.

"With child marriage, despite many years of propaganda, it still accounts for 20%," said Mr. Dao Hong Nhat - Head of Mu Sang Commune Health Station.

According to Mr. Phan A Chinh, Chairman of the People's Committee of Mu Sang commune, this is one of the difficult problems, despite the locality's efforts in propaganda and mobilization for many years.

The villagers call doctor Thanh "the midwife of Mu Sang".

18 years without missing a single call, without refusing a single birth - doctor Lo Thi Thanh is not only a village midwife, but also a midwife who brings faith and changes the mindset of an entire generation of ethnic minorities in the border areas of the country.

Despite the imperfections, Dr. Thanh continues his work, quietly and persistently.

In the middle of the Mu Sang mountains, where life and death can be just a steep path away, there was a woman who chose to stay.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the maternal mortality rate in mountainous and ethnic minority areas is two to three times higher than the national average, ranging from 100 to 150 deaths per 100,000 live births.

In particular, Hmong women have a risk of maternal mortality 7 times higher than Kinh women.

According to the report of Lai Chau Provincial Department of Health on maternal and child health care activities in the period of 2022-2024, the maternal mortality rate in ethnic minority areas in this locality is high.

Ms. Tran Thi Bich Loan, Deputy Director of the Department of Mothers and Children, Ministry of Health, said that changing people's awareness will take time due to long-standing customs.

"We still have limited facilities and medical staff to ensure the provision of services to ethnic minorities. This is one of the reasons leading to shortcomings in screening, examining and early detection of signs that can lead to obstetric complications and maternal death," said Ms. Loan.

Ms. Loan emphasized that, along with the state budget, international cooperation to increase equipment support and financial resources for disadvantaged mountainous provinces is an important solution.

The project "No one left behind: Innovative interventions to reduce maternal mortality in ethnic minority areas in Vietnam" is implemented by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with UNFPA and MSD to reduce maternal mortality in ethnic minority areas.

In Mu Sang commune (Phong Tho, Lai Chau), the project improved the birth rate at health facilities from 24% (2022) to 61% (2024) and the rate of women receiving regular prenatal check-ups from 27.2% to 41.7%.

Content: Linh Chi, Minh Nhat

Photo: Linh Chi

Design: Huy Pham

05/19/2025 - 04:44

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/suc-khoe/ba-mu-18-nam-bam-ban-khong-tin-minh-con-song-sau-bao-lan-vuot-deo-do-de-20250516122341750.htm

![[Maritime News] Two Evergreen ships in a row: More than 50 containers fell into the sea](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/8/4/7c4aab5ced9d4b0e893092ffc2be8327)

Comment (0)