Faced with the question, "What is human monopoly?", the first person I turned to was Xuan Lan. As an illustrator, despite having some recognition, she was one of the first and most directly threatened by AI-generated content.

On the X.Lan fan page, which has 187,000 followers, the artist wrote in English: "I'm not good with words, so I draw to tell my story."

But how do you distinguish between a story told by a human and one synthesized by a machine? Xuan Lan had never really thought deeply about that. She had developed the habit of observing small occurrences in life more than 20 years ago, when she decided to create a "Class Diary" for her middle school class. Later, Xuan Lan studied education and became an English lecturer, maintaining the habit of daily journaling throughout her adulthood, even if it was only short entries. The need to observe and record small events in life didn't serve her profession: Lan initially considered drawing just a hobby. She only started giving up teaching and becoming a full-time artist a few years ago.

We decided to work on each of Xuan Lan's paintings that I had selected.

Nonverbal signals

Consider this painting from 2022: Xuan Lan painted a woman standing at a bus stop in Taiwan (China). Through observation, the artist sensed that she was a Vietnamese migrant worker, and waited until she could confirm that the woman spoke Vietnamese.

With the introduction "A Vietnamese Woman in Taiwan," you've been led into the world of the painting. I can share my feelings, as an objective viewer with limited knowledge of painting. I don't see the woman's face, nor the most direct expression of emotion through her eyes and mouth, but I can still sense a part of her state of mind.

First, her attire—a T-shirt, leggings, and flip-flops—gives off a familiar feeling of being a fellow countrywoman (a style you'd rarely see elsewhere in the world). Even if only briefly, it suggests she's a manual laborer. The slanted, deep sunlight indicates it's likely afternoon. This woman, I surmise, is finishing her shift and on her way home.

She held her phone and video called a relative back home. It wasn't a special call, one where people eagerly gaze at the screen, eagerly look at the person on the other end. Perhaps it was just an everyday occurrence. She listened to the sound coming from the phone, her eyes looking out at the street. Although I couldn't see her eyes, I guessed they were vacant. Perhaps the distance between her hand holding the phone and her head allowed me to accurately imagine the scene of a migrant worker talking to someone back home while her eyes gazed listlessly at the street.

Even at this point, we, as Vietnamese people with the ability to understand the world around us, could insert dialogue directly.

[The phone speaker crackles, the words are unclear]

"The Taiwanese dollar has lost a lot of value lately. I'll see how things are next month and send the money all at once," the woman said.

So how did the artist decide to tell that story, without words?

She listed her decisions: First, the blank background. It indirectly informs the viewer of the woman's loneliness, or even alienation. The bus stop pole is the only object, signaling that she is on a journey from somewhere to somewhere.

Later, among the many postures she observed while waiting for the bus together, Lan deliberately drew the character's back slightly hunched, hands clasped in front of her stomach (an unconscious gesture often seen when people are uncomfortable, as the stomach is a vulnerable area of the body). The journey she was awaiting was certainly not an exciting trip .

Thirdly, she drew it so that viewers would realize the woman had bowed legs. The "combo" of bowed legs, tight sweatpants with the Adidas logo, blue flip-flops, and painted toenails in a bus station, made Vietnamese people recognize her as Vietnamese.

If we break it down further, we might find some highly technical details, like brushstrokes or materials. But that's probably something AI will be able to simulate. What AI, at least in the near future, won't be able to "understand"—or, as many scientists assert, it will never understand—is that all those details are interconnected, and most miraculously, they are connected to you, a Vietnamese person.

In that picture, even the smallest, unspoken signals—like the figure, the way she holds the phone, her hairstyle, her clothing, the color of her toenails, the shadows—can convey thoughts to us. We don't know who she is, whether she works as a cleaner or a nurse in Taipei, whether she's calling her husband and children or friends, whether she's going home to sleep or preparing to go shopping for dinner… but suddenly, a feeling of empathy arises within us. This empathy is quite random: for each person, it evokes different memories.

Think like a human

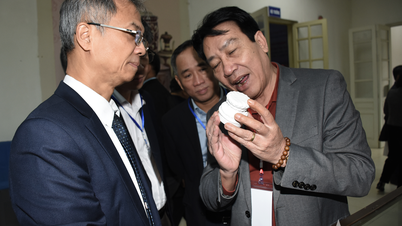

AI scientist Nguyen Hong Phuc believes that the ability to ask philosophical questions such as "Who am I? Where do I come from? Why do I exist?" is what distinguishes us from artificial intelligence. Furthermore, he believes that this is the capacity that enables a human worker to survive in the age of artificial intelligence.

With a PhD in computer science from the University of Delaware, Phuc has spent nearly a decade (even before artificial intelligence became a phenomenon thanks to ChatGPT) researching AI. His focus is on the impact of AI on the labor market, or the functioning of the economy in general.

During the interview process for this book, Nguyen Hong Phuc's main job was advising large businesses on AI applications.

In his lectures, the first thing Hong Phuc needs to clarify for business leaders is: what AI can and cannot do. What AI can do is something we can leverage (or use as a basis for downsizing); what AI cannot do is something we need to cultivate (or find suitable personnel for).

"AI is still at the stage of knowing, not understanding," Phuc asserted. "Knowing means it has grasped the information. But understanding the essence of that information, relating it to our understanding of the world outside, remains the exclusive domain of humans."

Most scientists agree: artificial intelligence will eliminate some forms of labor. He points to several content trends created by AI, for example, the wave of self-created avatars in the style of Ghibli animation or dolls, which emerged in early 2025. According to Phuc, these are signals confirming that the role of content producers, who once had a monopoly on creating online trends, is fading. “You can’t compete with AI if you still intend to attract the public with easy entertainment content. They work much more efficiently.”

Phuc asserted that within two years, from 2023 to early 2025, since the AI generation wave exploded, the number of images created by AI has been 10 times greater than the number of images created by humans since they invented the camera.

But it also has limitations. “AI is mimicking Van Gogh’s style, but it can’t yet create a new style of painting like Van Gogh did.” The role of humans, according to the scientist, must be a “creative, guiding, and innovative role.” At least in the medium term, before a super-intelligent artificial intelligence (ASI) more intelligent than humans is created.

"So what qualities need to be cultivated in this AI-driven era that threatens the labor market?" I asked.

"There's a concept that's actually quite old, so used that it's become tiresome, and that's systems thinking," Phuc replied. "When people encounter a problem, are they able to think about it within the context of the entire world they live in?"

The ultimate weapon: empathy.

AI is very strong in logic, and will continue to improve until it surpasses us in logic. But the human brain can work in a completely illogical way.

Let's delve deeper into the illogical aspects of human emotions. Here, I have another painting by Xuan Lan. It depicts a scene that perhaps every Vietnamese person is familiar with: a small family sitting on the roof of their house, amidst the floodwaters, waiting for rescue workers to arrive by boat.

In the collective memory, this is a scene associated with the harshness of nature, the hardships of people, and sometimes even suffering and loss. I showed this picture to Gemini 2.0 Flash.

Gemini, of course, recognized most of the objects in the picture and understood the context. Adults, children, a dog on the roof. A rescue boat. Floodwater covering the entire picture. When asked, "What emotions does this picture evoke?", it quickly listed: Anxiety, unease, fear, hope, pity. You don't need to be an AI expert to understand why the AI said that, because when compared to big data, the objects in the picture clearly suggest predominantly negative emotions.

But you've probably already noticed the problem here: this painting doesn't convey any negative emotions.

The AI didn't see the duck. Or perhaps it did see it but didn't realize that the duck leaving such ripples in the floodwaters was illogical. The duck is an illogical object. Only the author and we, as humans, truly "understand" why the duck is there. It's a deliberate absurdity intended to evoke a sense of peace.

The boy's face and body language don't reveal any fear; he looks like he's waiting for his mother to return from the market, or for the postman or the ice cream vendor with the squeaky music to pass by the alley. The proportions of the roof to the seated figure aren't "correct" either – they're drawn to a scale "to create cuteness," according to the artist.

The artist depicted the flood as if she were portraying a summer afternoon spent playing outside. It was a subjective decision. The deliberate combination of the concept of the flood (the negative) with the language and details of the painting (the positive) creates a new feeling in the viewer's heart. Optimism, peace, and hope are present here, without needing to be explicitly stated. And is this optimistic mood amidst tragedy, this understanding of it, a privilege unique to a Vietnamese person living within her community?

Dr. Nguyen Hong Phuc is not the only one in the world who believes that the ability to understand unspoken emotions, or empathy in general, between people, is the most significant advantage of future workers. This has been affirmed at numerous forums.

Of course, every worker in every field will have to answer the question for themselves: "What value does empathy actually have in my work?" and "How do I cultivate it?". Perhaps they've never even had to use that ultimate weapon in their lives: they've worked... like machines.

Source: https://vietnamnet.vn/doc-quyen-cua-con-nguoi-2490301.html

Comment (0)