Children's brains evolve faster

A new study has found signs that the brains of some teenagers age much faster than the average person — about 4.2 years faster in girls and 1.4 years faster in boys, according to the study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

There have been two previous studies on accelerated aging in children, but this is the first to provide detailed information on gender differences in aging.

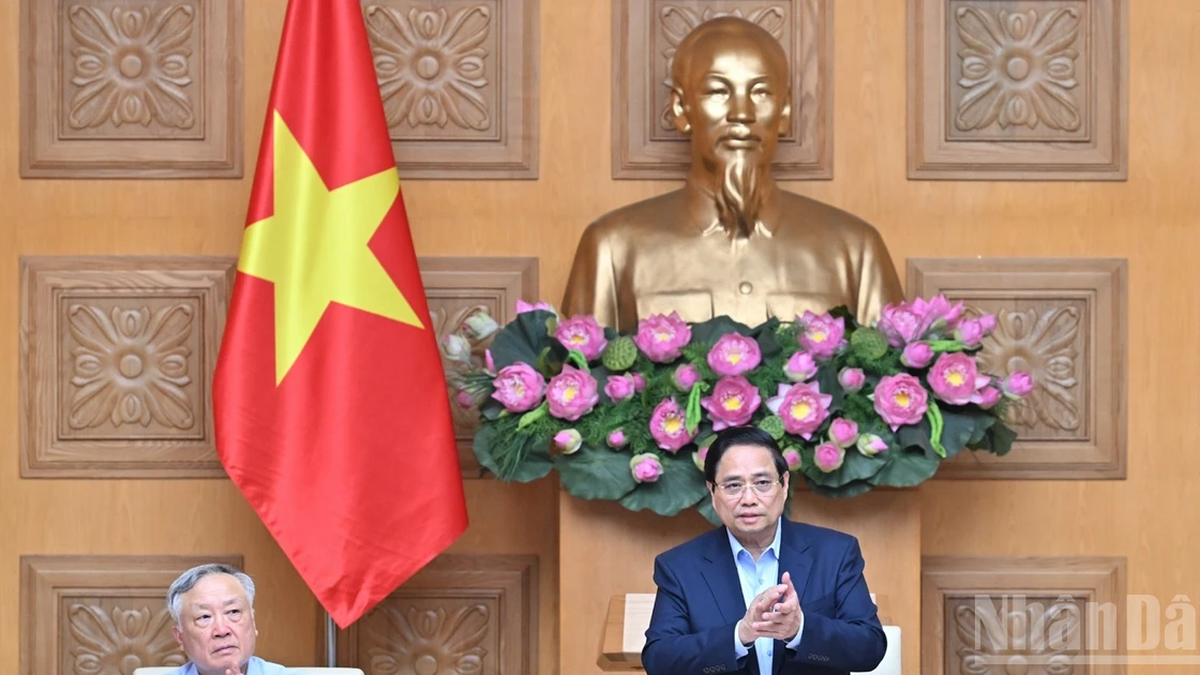

Illustration: Getty Images

"These findings are an important reminder of the fragility of the brain in adolescents, who need our support more than ever," said study author Dr. Patricia K. Kuhl of the University of Washington in Seattle.

The researchers originally planned to track the teens' brain development over time in a natural way, starting with MRIs — magnetic resonance imaging — that they performed on the participants' brains in 2018. They planned to do another scan in 2020.

But the pandemic delayed this second round of testing by nearly four years, with 130 participants living in Washington state between the ages of 12 and 20. The authors excluded young people who had been diagnosed with a developmental or psychiatric disorder or were taking psychotropic medications.

The team used previous MRI data to create a “standard model” of how 68 brain regions are likely to develop during typical adolescence, which they could compare to post-pandemic MRI data and see if it deviated from their predictions.

The authors say the model is similar to growth charts used in pediatric clinics to track height and weight in young children. Other researchers have used the method to study the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, autism, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and traumatic stress.

The study found that cortical thinning accelerated after the pandemic, occurring in 30 regions across both hemispheres and all lobes of the brain for girls and in just two regions of the brain for boys. Thinning rates were 43% and 6%, respectively, in the brain regions studied for both sexes.

According to the study, the cortical regions that rapidly thinned in girls were associated with social cognitive functions such as recognition, processing of faces and expressions, social and emotional experiences, empathy and compassion, and language. The affected regions in boys' brains were associated with processing objects in the visual field as well as faces.

Based on previous research, the authors suggest that these findings may be due to a phenomenon known as the “stress acceleration hypothesis.” This hypothesis suggests that when we are stressed, our brains may shift to an earlier stage of maturation to protect emotional circuits and brain regions involved in learning and memory, reducing the impact on structural development.

Need to monitor and help young people overcome difficulties

One factor that researchers have yet to figure out is whether these effects are permanent. “We know that the brain doesn’t recover or get thicker, but one measure of whether adolescents will recover after the pandemic is over and society returns to normal is whether their brains are thinning more slowly,” Kuhl added. “If that’s the case, we could say that the adolescent brain has recovered somewhat.”

Gotlib said it was important to ensure young people had mental health support. Wiznitzer advised limiting social media use and watching for changes in behaviour that reflect changes in mental health so they could be addressed as soon as possible.

Importantly, though the pandemic is largely over, its effects remain, Gotlib said. “There may never be a complete return to ‘normal.’ All of this is a powerful reminder of human fragility and the importance of investing in prevention science and preparing for the next pandemic.”

Ha Trang (according to CNN)

Source: https://www.congluan.vn/nghien-cuu-cho-thay-dai-dich-covid-19-anh-huong-toi-nao-bo-cua-gioi-tre-post311645.html

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman attends the seminar "Building and operating an international financial center and recommendations for Vietnam"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/28/76393436936e457db31ec84433289f72)

Comment (0)