(VHQN) - The famous French Sanskrit scholar - Abel Bergaigne was the initiator of the study of Cham inscriptions from the end of the 19th century. His first studies and translations of Cham inscriptions were published in 1893, but only mentioned inscriptions in Sanskrit.

Two years earlier, another famous scholar, Étienne Aymonier, wrote a treatise titled “First Study of Tcham (Cham) Inscriptions”, which only mentioned inscriptions written in the native language of the Cham people, namely Cham.

Long journey of research

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the study of Sanskrit and Cham inscriptions made great progress, thanks to the efforts of George Cœdès, Édouard Huber and especially Louis Finot, three members of the French École Française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO).

In 1906, another Paris University professor, Antoine Cabaton, continued this challenging work; although he published only a few studies on Cham inscriptions, he made an important contribution to the compilation of a modern Cham dictionary with Étienne Aymonier.

Also in the early 20th century, Cœdès compiled what he called a “General Catalogue” of Champa inscriptions (including Sanskrit and Cham). Each inscription was designated by Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3…) beginning with the letter “C.” (C = Campā).

Below each symbol is useful information such as: place of discovery, current storage location (if it has been moved elsewhere after being found); language of the inscription: Sanskrit or Cham; date; possibility of reproduction in public libraries; reference sources. This is truly like a “literary” directory for those who want to study Cham inscriptions.

The first edition of this work, with 118 entries, was published in 1908, the second edition, with 170 entries, appeared in 1923; appendices were published in 1937 with 196 entries, but were supplemented to reach 200 entries in the 1942 edition. The list was then abandoned; decades passed without any significant records of newly discovered inscriptions.

With very little work on Cham epigraphy after the EFEO scholars published in the 1920s and 1930s, epigraphic research at EFEO and elsewhere came to a complete halt due to World War II and the subsequent struggles for independence of the Vietnamese people.

At that time, the study of Sanskrit inscriptions received more attention and therefore made more progress than the study of Cham inscriptions.

Despite serious gaps in knowledge about Cham inscriptions, there were a number of works of art history and political history published in the 20th century, the content of which was largely based on these published inscriptional materials; and to this day they are still consulted and used by scholars.

It should be emphasized that the authors of those works were unaware that the reference to Cham inscriptions was based on incomplete data. And even if they were aware of this deficiency, to some extent, that awareness would have been completely lost in the next generations of researchers.

Notes on characters and language

Fortunately, in the first decade of the 21st century, the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient in Paris continued to support the collection and translation of Cham inscriptions. This project, called “Études du corpus des inscriptions du Campa III (ECIC III)” (Studies of the Collection of Champa Inscriptions III (ECIC III), was directed by Prof. Arlo Griffiths - a famous expert on Southeast Asian inscriptions and his colleagues.

They re-examined the translations of the 1930s generation of scholars, including many unpublished inscriptions along with recently discovered inscriptions. They also reviewed previous translations, corrected reading errors, and improved the wording of older texts.

The first published work of this project was “Champa Inscriptions at the Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture” published in 2012 in Vietnamese and English. In this work, most of the museum’s inscriptions, including intact stelae and fragments, were carefully translated and annotated into English and then translated into Vietnamese.

When studying Cham inscriptions, scholars need to distinguish between the writing system and the language. The two common languages used for writing in the Champa kingdom were Sanskrit and ancient Cham, but only one writing system was used to write both languages.

Like most ancient civilizations in Southeast Asia, the history of Cham inscriptions began with texts in Sanskrit, written in a script originating from India. This script had an alphabet that was formed in the 3rd century BC under the reign of King Aśoka (A Dục Vương), who ruled over Northern India, called “brāhmī lipi”, meaning “the system of characters (lipi) of Brahma”, after the name of the god of knowledge Brahma.

Several centuries after its creation, the Brāhmī script differentiated into two different forms used in North and South India, namely North Brāhmī and South Brāhmī. According to scholars, the dominant script in Southeast Asia is the South Brāhmī script.

Inscriptions were created to serve not only earthly purposes but also supernatural ones. In most cases, they also represented the presence of kings.

We can see that the difference in the use of Sanskrit and Cham reflects the secular nature of a text, or part of it: the more it deals with the eternal - the fame of kings and the power of gods - the more likely it is that Sanskrit will be used; but if it deals with the needs of social life, then Cham will be used more.

Initial thoughts on conservation

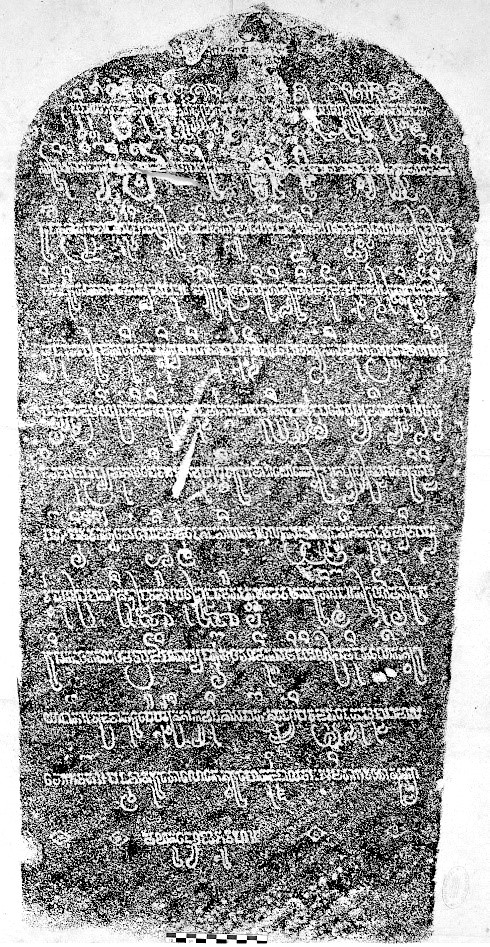

Among the collected Cham inscriptions, most originate from My Son, some from other places in Quang Nam and Da Nang. In this collection, there are famous inscriptions with rich content and clear dates such as the My Son steles, which were erected continuously through the dynasties from the 4th - 5th centuries until the 13th century.

The Buddhist inscriptions of Dong Duong, dated 875, and An Thai, dated 902, are extremely valuable sources for learning about the unique thoughts of Champa and Southeast Asian Buddhism. Preserving Cham inscriptions is an urgent issue, because they are valuable and authentic references to the history of the Champa kingdom in general and of ancient Quang.

Particularly in Quang Nam, which is one of the places where many important inscriptions were found, the preservation of this type of heritage becomes more urgent. In the immediate future, we need to have long-term projects to collect the engraved copies of the inscriptions that are still kept at relics such as Khuong My, Chien Dan, Huong Que, Dong Duong, Bang An... or are being preserved at the National History Museum in Hanoi and the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Da Nang.

In addition, you can contact the Library of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient in Paris, which is the place that stores the most Cham inscriptions, to request copies. The collected inscriptions should not only be preserved and served at the Quang Nam Library, but also displayed at the Quang Nam Museum and the My Son Museum to serve visitors in need, as a form of introduction and education for future generations to continue learning and researching.

Source

Comment (0)