During the difficult subsidy period, the young people in my neighborhood on Hang Bot Street rushed out onto the streets to... make a living.

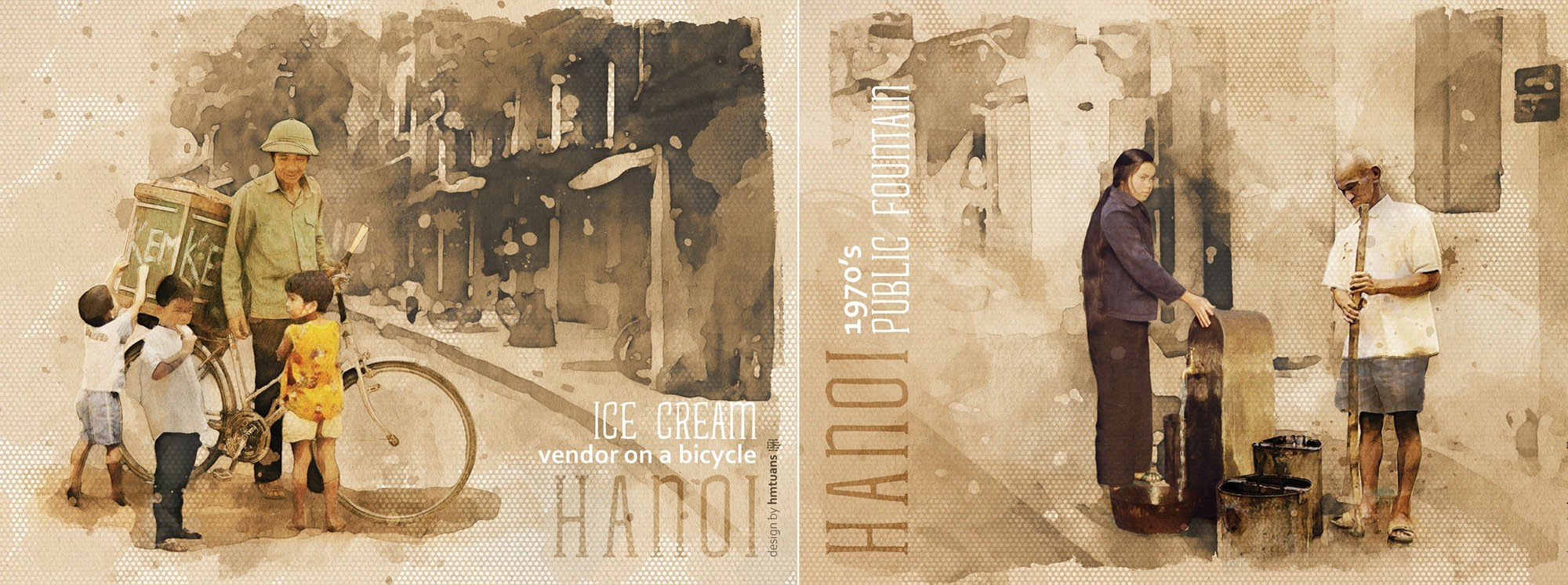

Paintings by artist Ho Minh Tuan, son of author Ho Cong Thiet, depicting an ice cream vendor (left) and a water carrier in Hanoi during the subsidy period.

In front of our house was a large courtyard, but several food stalls had already taken over, establishing a stable wholesale business. To "start their business," the young men in my neighborhood had to cross the road to the intersection of Hang Bot and Phan Van Tri streets, where there was a large sidewalk, convenient for passing vehicles to park, and always bustling with people – these were the potential customers for the box with the neatly written words: "Pen engraving and ballpoint pen ink refilling."

Nam, Mr. Thao's son, is intelligent and quick-witted, inheriting the qualities of his father – an engineer at a railway carriage factory in Gia Lam. During the subsidy period, like other "entrepreneurial talents" on Hang Bot Street, he tried his hand at various jobs before settling on engraving pens and refilling ballpoint pen ink.

He painstakingly took the tram every day to the banyan tree in front of Ngoc Son Temple at Hoan Kiem Lake to study under Master Le Van Quy, perhaps the most famous pen engraver of that time. When he first started, Mr. Quy saw a house on Hang Gai Street with a pen engraving machine; the strokes on the pen body were perfectly even but seemed rigid and stiff. He then sharpened the iron himself, crafting a special engraving knife with a curved, sharp tip. He practiced engraving on plastic and wood; once he became proficient, he began engraving for customers on pen bodies, wooden paintings, and even lacquer paintings. His elegant engravings and beautiful, realistic illustrations made him increasingly famous. In the Hoan Kiem Lake area, there were many pen engravers at that time, but customers often entrusted their precious fountain pens to Mr. Quy to engrave their names. Many generous people even paid extra, asking Mr. Quy to engrave additional images such as the Turtle Tower or The Huc Bridge onto the pen. He used his pen engraving skills to raise all four of his children to be successful adults.

Nam was a very diligent apprentice. While the master worked, he sat motionless, his eyes glued to each stroke of the pen as it engraved onto the bodies of fountain pens. Whenever someone passed by and glanced at the master engraving pens, Nam would eagerly run out to greet them, park their bikes, and lead them to the low wall surrounding the banyan tree, where customers sat waiting for their turn to have their pens engraved.

After studying with Mr. Quy for a while, Nam opened a shop on Hang Bot Street and soon had many customers. He was young and intelligent, so even a meticulous person would find it difficult to distinguish whether the engraved characters on the pens were his own or his teacher's.

Pens from the subsidy era were cherished and valued. Many people even had small, hand-sewn silk pouches to hold their pens. Their names were engraved on the pen's body, both as a hobby and to assert ownership, preventing others from accidentally taking it. If the pen was a Parker brand, the owner would take even more care. They would sit on the sidewalk, admiringly watching Nam engrave the pen and marveling at his skillful craftsmanship.

Besides the owner's name, pens engraved in Hang Bot, if they include illustrations, all follow a unique style, mostly depicting the Khue Van Pavilion in the Temple of Literature. Depending on the remaining space on the pen's body after engraving the name, the Khue Van Pavilion, under Nam's hand, appears from various angles and with exquisite detail.

Besides engraving pens, Nam's shop also offers ballpoint pen ink refilling services.

When customers came to refill their ballpoint pens, Nam would first remove the ballpoint tip from the ink cartridge, clean off the old ink with alcohol, and then run the tip across the paper to check if it rolled smoothly. If the tip was sticky and difficult to roll, he would soak it again in a dish of alcohol. Nam had a small box to hold various sizes of ballpoint pens. If a ballpoint pen was worn out and about to fall out, he would use a pointed stick to push the old ballpoint out and replace it with a new one.

After assembling the pen, he used a syringe to pump ink into the cartridge. He held the ink-filled cartridge and twirled it on a piece of cardboard. The ink clung to the ballpoint tip and left a mark on the paper. The thickness of the stroke depended on the size of the ballpoint. Once finished, he reassembled the cartridge and respectfully handed it to the customer. Every customer happily paid without haggling. During the subsidy era, restoring such a rare and valuable pen without having to travel all the way to Hoan Kiem Lake or Cua Nam meant no customer bothered about the price.

In the early days when Nam started refilling ballpoint pens, we would occasionally run out and stand behind him like bodyguards to prevent customers from... beating him up. Sometimes, customers would come to complain, carrying pens with ink stains, or even wearing shirts completely covered in ink. Because the ink was waste ink, it was very diluted and would gradually leak through the pen and seep out. At that time, Nam lacked experience and didn't know how to inject glue into the ink cartridge. He called it glue to sound impressive, but in reality, he was told to mix glutinous rice flour into a paste and inject it into the bottom of the ink cartridge. This glue would stop the leakage, and his reputation would skyrocket. (to be continued)

(Excerpt from the work " Hang Bot Street, Trivial Stories That Make Me Remember" by Ho Cong Thiet, published by Labor Publishing House and Chibooks, 2023)

Source link

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man visits and works with the National Assembly Committees and the State Audit Office.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/23/1771848141941_ndo_br_bnd-6798-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)