According to Sixth Tone, there are approximately 170 million children aged 5-12 in China, and one in three of them own a smartwatch. Originally marketed in the 2010s as a smartphone alternative for young children, the kiddie watch – specifically the Xiaotiancai (Little Genius), or imoo in the international market – has morphed into a mini social platform with many implications.

Seemingly harmless features like leaderboards, like collections, and status logs have turned devices that were meant to be safe into tools for peer pressure and fostering online interaction addiction, according to Chinese media investigations.

On a screen the size of an Oreo, kids can make friends, post status updates, accumulate likes and comments – similar to Instagram or WeChat. But this “unsupervised” environment has created a new social reference frame based on likes, making many kids competitive and anxious.

A 16-year-old girl in Shandong province wrote on the social network Xiaohongshu: “My schoolmates have more than 5,000 likes and always show off. I have only had 100 likes in a year using my watch. Can someone help me?”

In just 9 days of connecting with strangers and spending most of her free time "farming" for interactions, she reached 1,000 likes.

In the Xiaotiancai community, accounts with more than 600,000 likes are called “gods.” Having or being friends with a “god” is seen as social capital, helping children get more attention in real life.

Each account can only have a maximum of 150 friends. Friends with “low interaction” are easily deleted, even close friends in real life, causing many parents to worry because children equate real friendship with liking.

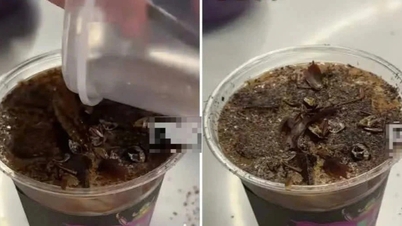

As competition escalated, a gray market emerged around Xiaotiancai, with children buying and selling accounts with large numbers of likes to “level up” quickly.

A 12-year-old boy said he sold his account with 242,000 likes for 80 yuan (about $11). On e-commerce platforms like Taobao, there were many shops specializing in “increasing interactions” for Xiaotiancai.

On Xianyu, a weekly account management service costs 30–50 yuan, while “automation” packages that use bots to generate more than 1 million likes cost as much as 1,000 yuan (about $140).

An online store owner said: "The customers are very young so the price cannot be too high, the principle is to make little profit but sell a lot."

Many parents believe the devices are straying from their original purpose. “Every hour a child spends staring at a watch is time lost for learning, playing and socializing,” said Jin Ceyuan, a Beijing resident. “It is no longer a safety device but a thief of childhood.”

Under pressure from public opinion, Xiaotiancai (in the same ecosystem as Vivo and Oppo) said users can turn off social features. This company is leading the children's watch market with a 27% market share.

However, legal experts warn that the company may face legal risks, as China's Juvenile Protection Law (amended in 2020) requires platforms providing services to children to take measures to prevent internet addiction.

“Teenagers always crave recognition from their friends. We can’t completely ban it, but we need stricter management from the producers, and parents and schools need to provide positive guidance,” said Liu Zhen, a psychologist at the Shanghai Mental Health Center.

Chu Zhaohui, a researcher at the China Academy of Educational Sciences , said the story reflects the larger challenge of digital education: “Internet-enabled devices need to be evaluated based on whether they support or hinder children’s social development. Smartwatches encourage quick interactions but are unlikely to replace face-to-face communication – where children learn respect, read emotions and develop empathy.”

Source: https://baotintuc.vn/mang-xa-hoi/khi-nhung-chiec-dong-ho-thong-minh-tro-thanh-ke-danh-cap-tuoi-tho-20251119154017518.htm

![[Photo] The Standing Committee of the Organizing Subcommittee serving the 14th National Party Congress meets on information and propaganda work for the Congress.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/19/1763531906775_tieu-ban-phuc-vu-dh-19-11-9302-614-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam receives Slovakian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defense Robert Kalinak](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/18/1763467091441_a1-bnd-8261-6981-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh and his wife meet the Vietnamese community in Algeria](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/19/1763510299099_1763510015166-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)