Not only does it provide shade to cover time, each tree trunk and each leaf bears the mark of a bloody time - where steadfast revolutionary soldiers were imprisoned and tortured in the infamous "hell on earth" of the 20th century.

The banyan trees are an indomitable symbol of patriotism, steadfastness in the face of shackles and violence. They are a silent but profound reminder of the great sacrifices that have made our country what it is today.

“Revolutionary banyan tree” in front of solitary confinement cell number 9 - where former female political prisoner Muoi Dao and her comrades were imprisoned.

“Revolutionary Banyan Tree” through the story of “prisoner without number”

Con Dao in the historic April days welcomed tens of thousands of tourists to visit and travel .

Some people come here to witness the “hell on earth” that they had previously only heard about through books or stories; some former prisoners of Con Dao, after many years of returning to the mainland, come back just to find memories of the war and the pain of war; some “prisoners without a number” come to Con Dao to once again witness their relatives who more than half a century ago “lived an ideal life, died gloriously”, stubbornly fighting against the harsh regime of the prison guards.

They are called “prisoners without numbers” because their mothers were imprisoned in Con Dao. They were born in prison or were arrested with their mothers and grew up in prison, living with other prisoners, except they did not wear numbered shirts...

Ms. Bui Thi Xuan Hanh (born in 1967, residing in Phu Nhuan district, Ho Chi Minh City) is one of many "prisoners without numbers" who came to Con Dao on April 30 to revisit the "tiger cage", where more than half a century ago, her mother - Mrs. Le Thi Tam, was imprisoned by the French colonialists for 6 years.

Recalling painful and tragic memories, Ms. Hanh told us the story of her mother using young banyan leaves to cure her comrades and save their lives. The banyan tree was a secret place to hide documents and leaflets. The dry banyan leaves helped the prisoners keep their backs warm during the bitterly cold days.

Putting her hand on the trunk of the banyan tree in front of Phu Hai prison, Ms. Hanh choked up: “Returning to Con Dao this time, I fulfilled my mother’s last wish, which was to visit “tiger cage” number 9 - where she was brutally tortured by the prison guards; to visit the banyan tree where she hid documents from 1969 until the day of liberation. I was born in Thu Duc prison and became a “prisoner without a number”...

In August 1966, while working for the Saigon Special Forces, her mother was arrested. At that time, she had the nickname Muoi Dao (real name Le Thi Tam, affectionately called Aunt Muoi). She was arrested one afternoon while secretly working at Ba Chieu market (Saigon - Gia Dinh) and was locked up in Thu Duc prison.

At that time, my mother was one month pregnant with me. “In March 1967, I was born in prison. My mother recounted that I was born so tiny, black like a mouse in the palm of a hand, no one dared to hold me because I was so small. I was held and raised by my aunts and mothers in prison,” Ms. Hanh said.

After more than 3 years of brutal torture but having to "give up on the stubborn communist", her mother was exiled to Con Dao at the end of 1969. Ms. Hanh was sent back to her aunts and mothers in Thu Duc prison to protect her...

In the "tiger cage" - cell number 9, from the end of 1969 to the end of April 1975, Ms. Muoi Dao was tortured by the prison guards using all kinds of torture methods, but her fighting spirit was not shaken.

After many months of imprisonment in a dark cellar, one autumn afternoon in 1971, Ms. Muoi Dao was “allowed to go out for some fresh air” by the prison guards. Taking advantage of a loophole, she sent secret information “ready for liberation day” to the banyan tree in front of the solitary confinement cell.

“My mother hid that document under the banyan tree and then transferred it to the revolutionary base safely. On April 30, 1975, Con Dao was liberated; on May 5, 1975, my mother was transported back to the mainland by a navy ship in the “Victory 2” group. In many stories about her revolutionary life, my mother still remembers the banyan tree in front of cell number 9, Phu Hai camp - the place that witnessed so much pain, humiliation but also so much pride of her and the prisoners,” Ms. Hanh shared.

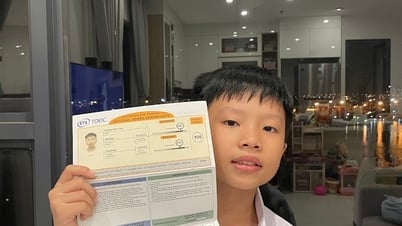

Mrs. Muoi Dao (Le Thi Tam) with sacred revolutionary relics

Talking Objects

In the old house sharing the same gate with the neighbors at 17 Le Tu Tai, Ward 14, Phu Nhuan District, Ho Chi Minh City, Ms. Hanh showed us many artifacts that Mrs. Muoi Dao brought back from Con Dao 50 years ago. Among them were two sacred relics that were associated with Mrs. Muoi Dao throughout her revolutionary life.

The first keepsake is a painting that her mother embroidered in 1971-1972. Missing her daughter so much, Mrs. Muoi Dao secretly burned dried Indian almond leaves to ashes, then mixed them into ink. She took the fabric from her ao ba ba, dyed it with ink and spun the thread to embroider.

The painting conveys the emotional message of a mother in a dark prison to her little daughter on the mainland. In the distance is the morning sunrise behind the mountain.

A ship is anchored in the middle of the sea full of aspirations, ready to transport Con Dao prisoners back to the mainland on the day of victory; the image of a little girl waiting for her mother; on it is written the words "Sending my love to you, memories of Con Dao prison on February 6, 1972"...

Holding the embroidery, Ms. Hanh's eyes filled with tears: "I have kept this embroidery for 50 years, it has become a priceless and sacred keepsake for my family. Every time I look at the painting, I remember my mother.

My mother devoted her whole life to the revolution. The 6 years she was imprisoned by the enemy in Con Dao prison were the same amount of time she was steadfast and brave. She is no longer here, but her revolutionary fighting spirit, her silent sacrifice, her communist spirit, and her life of devotion to the people and the country are always the spirit that my husband, my children and I learn and follow.

The second souvenir Ms. Hanh showed me was a dry banyan leaf with a picture of her as a child. She said that in 1972, one afternoon, the prison guards took Ms. Muoi Dao out of cell number 9, and taking advantage of a loophole, she stuffed a banyan leaf into her body.

The next day, she used a needle to prick a leaf in the shape of her little daughter. That special leaf was hidden in the root of the banyan tree in front of the prison cell, then transported to the mainland.

“When I was young, I didn’t understand much. On the day the country was reunified, my mother and I met. She told me about the banyan leaf and the years of imprisonment in Con Dao. We hugged each other and cried with joy. Only later did I understand why in the dark prison, my mother embroidered pictures full of aspiration,” Ms. Hanh emotionally shared.

Time flies like an arrow, the dust of time can blur the memories of former prisoners of Con Dao, but the evidence of war cannot fade. The giant banyan trees here still stand tall between the sky and the earth, like living milestones recording the years of blood and fire.

They are not only a testament to the indomitable will and silent sacrifice of revolutionary soldiers, but also a symbol of a glorious time that cannot be forgotten.

50 years ago, each banyan tree was like an indomitable soldier. Today, after half a century, they still carry the heroic vestiges, breath and shape of the Fatherland.

Con Dao Banyan has surpassed the limits of a tree species - becoming a sacred heritage of national history, a silent but profound reminder of the value of independence, freedom and patriotism.

Source: https://baovanhoa.vn/chinh-tri/nhung-cay-bang-mang-dang-hinh-to-quoc-126988.html

Comment (0)