The world's largest creature is gradually being "eaten" (Photo: Getty).

In the Wasatch Mountains of Utah, a unique giant creature has been quietly creating an entire ecosystem for millennia. Beneath the appearance of a birch forest with thousands of fluttering leaves, this is no ordinary forest, but a single-celled, asexual organism weighing up to 6,000 tons.

The creature is known as Pando, which is Latin for “spreader.”

The world's largest creature

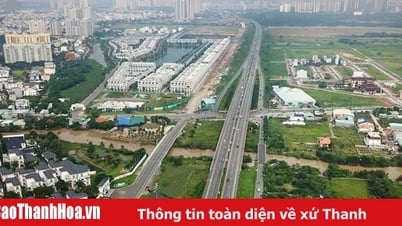

Pando is essentially a clonal colony of 47,000 quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) stems, all genetically identical, growing from a single underground root system.

The colony spans an area of approximately 43 hectares and is recognized as the largest single organism ever recorded on Earth in terms of mass.

Completely different from the small aspen populations common in North America, Pando has always been emphasized by scientists for its extraordinary nature.

Aerial sketch of Pando, with Fish Lake nearby (Photo: TC).

Pando has been around for 14,000 years, since the last ice age. Although each individual tree only lives for about 130 years, the mother root system continually produces new trees, creating a closed cycle of regeneration.

This cycle nurtures a complete ecosystem, including at least 68 plant species and countless animals such as foxes, birds, deer, beavers, pollinating insects and wildflowers.

Gradually being "eaten away" from the inside

Despite its incredible size and age, Pando is quietly declining. Surprisingly, this decline is not because humans are cutting it down, but because it is being eaten from within.

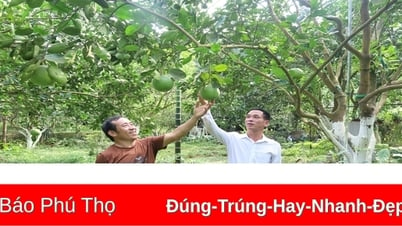

The main culprits are familiar herbivores: deer and elk. The loss of natural predators like wolves and cougars—which once kept deer populations in check—has led to a rapid increase in these herbivores.

Deer eat Pando tree shoots (Photo: TC).

These animals are particularly fond of gathering in the Pando area because it is a protected forest where hunting is not allowed. As a result, any shoots that emerge from the root system are nibbled off at the top, resulting in premature death. Pando continues to produce new trees, but the regeneration process is stifled from the start.

In fact, only a small area fenced off decades ago for ecological restoration has seen successful regeneration. There are no deer or elk present, and new trees have grown densely.

Along with herbivore pressure, plant diseases are also taking a serious toll on Pando. Researchers have documented at least three major diseases, including sooty bark canker, leaf spot, and stem-destroying fungus. Although poplars have adapted to the pathogens over thousands of years, the combination of disease and lack of regeneration is weakening the longevity structure of the population.

The most worrying threat, however, comes from climate change. After thousands of years of stable post-glacial conditions, Pando now faces record-breaking summer temperatures, prolonged droughts and dwindling water resources.

With Fish Lake—the nearest body of water—out of reach of the tree's root system, Pando is unable to access new water sources. This makes leaf formation in the spring increasingly difficult, reducing the area available for photosynthesis and the organism's ability to survive.

While there hasn’t been much scientific research specifically on Pando, other aspen populations in North America are grappling with similar pressures from changing rainfall patterns, erratic weather patterns, and wildfires. A single severe fire, for example, can wipe out thousands of years of biological history in a matter of hours.

Still, hope is not lost. Pando has weathered major upheavals with the arrival of Europeans in the 19th century, the rise of recreation in the 20th century, and past pandemics and wildfires.

Scientists are now working closely with conservation groups, notably Friends of Pando, to study the resilience of the majestic creature. They are also using 360-degree video technology to help the public around the world access and understand the importance of Pando.

"Pando is more than just a single organism. It is a biological symbol of vitality, adaptation and natural connection," said Richard Elton Walton, a postdoctoral researcher in Biology at Newcastle University.

"Saving Pando is not simply about protecting one creature - it's about preserving an entire ecosystem, part of Earth's most vibrant living history."

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/sinh-vat-lon-nhat-the-gioi-dang-dan-bi-an-thit-20250611071213046.htm

Comment (0)