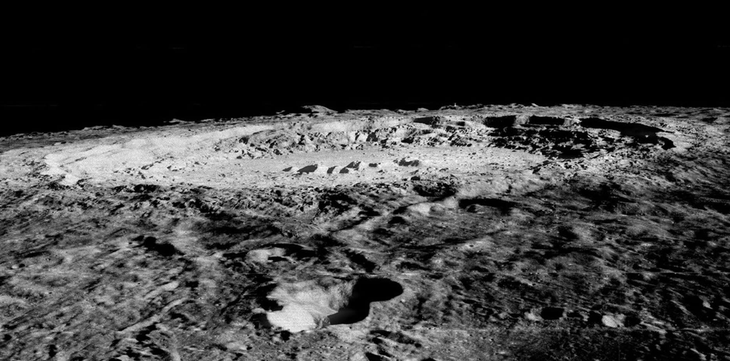

Currently, quite a few international missions, including NASA's Artemis, are preparing to explore the far south polar region of the Moon, which is believed to have the most strongly magnetic rocks - Photo: NASA/JPL/USGS

Since the 1970s, when NASA brought back samples of lunar rocks to Earth during the Apollo missions, scientists have discovered something strange: many rocky areas on the lunar surface, especially on the far side, show signs of strong magnetism. This is contrary to the fact that the Moon currently does not have a protective magnetic field like Earth.

A powerful meteorite impact billions of years ago may have temporarily amplified the Moon's weak magnetic field, leaving a "magnetic signature" in rocks that can still be measured today, a new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) suggests.

According to the team's simulations, a sufficiently powerful impact, possibly the one that formed the Imbrium crater, would have vaporized the Moon's surface, creating a cloud of superheated, electrically charged plasma.

This plasma enveloped the Moon and concentrated magnetic energy on the opposite side of the impact. The resulting magnetic field in that area increased sharply in a short period of time, enough to magnetize rocks in the area for even tens of minutes.

In addition, seismic waves from the collision also spread across the Moon and converged far away, causing electrons in the rock to "vibrate" at the exact moment the magnetic field reached its peak, thereby "locking" the magnetic field into the rock like a geological photograph.

"It's like you toss a deck of cards into the air in a magnetic field, each card has a compass needle. As they fall, they align in a new direction, which is how the stone gets magnetized," said Professor Benjamin Weiss, a member of the research team.

This process happens very quickly, in less than an hour, but it is enough to leave a permanent magnetic mark. That is why today, probes can still measure unusually strong magnetic fields on some rocky regions on the far side of the Moon.

Thus, the Moon itself once had a weak magnetic field from its small molten core, but only when combined with large-scale impact events did this field become amplified enough to affect the rocky crust.

Currently, several international missions, including NASA's Artemis, are preparing to explore the far south polar region of the Moon, which is believed to have the most strongly magnetized rocks.

If the rocks here bear both signs of seismic shock and ancient magnetism, this would confirm the hypothesis that meteorite impacts magnetized lunar rocks, one of the oldest mysteries of planetary geology.

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/vi-sao-da-mat-trang-co-tu-tinh-du-mat-trang-khong-co-tu-truong-202505241027449.htm

![[Photo] Festival of accompanying young workers in 2025](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/25/7bae0f5204ca48ae833ab14d7290dbc3)

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong receives Lao Vice President Pany Yathotou](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/25/958c0c66375f48269e277c8e1e7f1545)

![[Photo] Memorial service for former President Tran Duc Luong in Ho Chi Minh City](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/25/c3eb4210a5f24b6493780548c00e59a1)

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong receives Vice President of the Cambodian People's Party Men Sam An](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/25/6f327406164b403a8e36e8ce9d3b2ad2)

Comment (0)