While China moves quickly with a strategy to “nationalize” AI education , the US – though lagging behind – has the potential to accelerate thanks to the private sector and the creativity of a decentralized education system.

This article does not go into comparing superiority and inferiority, but focuses on analyzing prominent strategies, reform movements within the US, upcoming challenges, and what Vietnam can learn.

China: Shape from the root, implement comprehensively

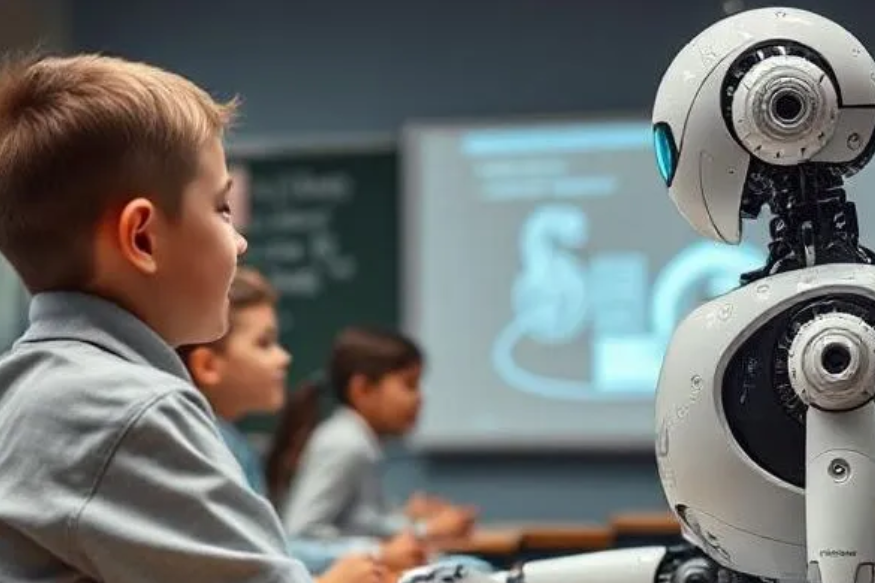

China has chosen a path that does not complicate the curriculum framework – instead of creating a new subject called “AI”, the country integrates AI content into existing subjects such as math, science , technology, and engineering. From primary school, students are familiar with computational thinking. In secondary school, they approach basic programming and problems using data. In high school, advanced content such as computer vision, chatbots, and machine learning models are piloted.

The key is the implementation method. First, the government plays a central role in policymaking and coordinating resources nationwide. Second, technology companies step in to provide software, materials, and educational technology support – from iFlytek to Baidu, all have “AI for schools” programs. Third, top universities like Tsinghua and Fudan are tasked with creating curriculum, training teachers, and evaluating the quality of implementation.

In particular, the Chinese government has developed a national AI learning platform that allows students from all regions – including poor areas such as Gansu and Guizhou – to access the same content as students in Beijing or Shanghai. Virtual AI assistant teachers are deployed to support personalized lessons, helping students progress according to their own abilities. In this way, China not only creates an AI education policy, but also ensures equitable popularization – a prerequisite for overall technological strength.

America: Reform from the bottom up, businesses lead

While China is working from the top down, the US is restructuring from the bottom up. The decentralized education model has been a drag on national education reform, but in the age of AI, it opens up flexible space for experimentation. In parallel with the open letter from more than 250 CEOs to state governors, a series of large technology companies such as Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and NVIDIA have launched various programs to support public schools since a few months ago: providing free AI learning software, training teachers, donating equipment, and designing sample courses.

Some school districts, such as Lamar (Texas), Oakland (California), or Baltimore (Maryland), have even implemented a fully AI-powered classroom model: each student learns at their own pace; teachers act as progress managers and provide intensive support. Students interact with AI chatbots during math class, use computer vision to do biology experiments, and learn programming through AI-integrated games.

The federal government is also getting involved. The president created an “AI Education Task Force” to develop curriculum standards, connect disparate initiatives, and facilitate industry participation without regulatory hurdles. The Department of Education is working with states to develop open-source curricula, create teacher training centers, and fund pilots in underserved areas.

Thus, the US does not need to catch up with China in terms of administrative speed – which is almost impossible – but takes advantage of its competitive advantages: the innovative power of private enterprises, the open learning ecosystem, and the diversity of educational models at the local level.

Bottlenecks and challenges

However, both the US and China face major hurdles when it comes to AI entering education – not just technical, but also social and ethical.

First, the issue of data security. When students use AI tutors, data on their learning behavior, emotions, information processing speed, and even how they ask questions are collected. Without legal protection, companies can completely commercialize this data for advertising, or use it to adjust content in a way that benefits them.

Second, the risk of technological polarization. In the US, the gap between rich (often urban) and poor (rural, minority) school districts will widen without adequate federal investment. In China, the “AI teaching assistant” model may work in areas with good infrastructure, but is likely to be useless in areas without basic digitalization.

Third, the problem of “shaping thinking” through algorithms. When AI not only teaches but also “suggests” how to learn and how to answer, students may unconsciously absorb the biases hidden in the algorithm. From there, education loses its role in shaping independent thinking – the core of a democratic society.

To overcome these challenges, the US is proposing an “AI Privacy in Education Act” that would require algorithmic transparency, prohibit the sale of education data to third parties, and mandate end-to-end encryption for all AI learning systems. China, by contrast, has centrally oriented content control but lacks independent oversight from civil society.

What can Vietnam learn?

Vietnam is at a starting point in designing AI education. The question is not whether to “choose the American or Chinese AI education model”, but: Which approach should Vietnam choose that is suitable for its current infrastructure, population, and teacher qualifications?

First, there are many positive things Vietnam can learn from China. Schools in Vietnam can integrate AI into existing subjects without creating new ones. The Ministry of Education and Training needs to provide a minimum competency framework for computational thinking and AI at each level of education. Building an open, shared digital learning resource nationwide will help reduce inequality between urban and rural areas, lowland and mountainous areas.

Second, a positive point from the US that Vietnam can refer to is mobilizing the private sector to participate in teacher training and providing educational AI platforms. Companies such as FPT, Viettel, VNPT, VNG, CMC... can play a similar role to Microsoft, NVIDIA in the US - not only investing in infrastructure but also developing learning software according to open standards. At the same time, teacher training programs via digital platforms should be deployed widely, with certificates issued according to the MOOC model - Issuing certificates recognizing the completion of open online courses (usually free), provided by reputable universities or digital platforms.

Third, Vietnam should soon consider establishing a national coordination center – possibly the “National AI Education Committee” – to ensure program consistency, connect businesses – schools – the state, and connect national learning data. However, this center should not operate according to a rigid administrative mechanism, but in an open, flexible and transparent coordination direction.

Students are the center, the first AI citizens of the 21st century

The AI race between the US and China has entered a phase where education is no longer a tool to support technological development – it has become a decisive foundation for national innovation capacity. The US lags in central policy, but has an advantage in private ecosystem and flexibility. China can deploy uniformly quickly, but faces questions about content control and diversity of thought.

Vietnam does not need to be a “copy” of anyone. The most important thing is to start now: build an integrated AI program from primary school level, train teachers widely, make learning devices popular, and set up an effective public-private coordination institution suitable for Vietnam’s conditions. Artificial intelligence will not wait, and countries that do not act early will be left behind forever in the education and technology race of the 21st century.

Source: https://vietnamnet.vn/chay-dua-giao-duc-ai-va-bai-hoc-cho-viet-nam-2400069.html

![[Photo] 60th Anniversary of the Founding of the Vietnam Association of Photographic Artists](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764935864512_a1-bnd-0841-9740-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man attends the VinFuture 2025 Award Ceremony](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764951162416_2628509768338816493-6995-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)